On Monday Twitter’s board of directors accepted a $44 billion bid from Elon Musk, who plans to “make Twitter better” and take it private.

Regardless of whether the deal will eventually go through, buying media is a sport only the billionaire class tends to play.

You’ll remember that back in 2013 former Amazon CEO, Jeff Bezos, purchased the Washington Post. And long before that, Rupert Murdoch went on a buying spree that included Twentieth Century Fox in 1985, book publisher HarperCollins in 1989, and The Wall Street Journal in 2007.

It’s naive, of course, to assume rich landlords will prescribe their media outlets what to print. But it is odd that in the case of the Washington Post there suddenly was a need for nuance around the question of if and how to tax the ultra-rich. And quite unapologetically, Murdoch’s empire has single-handedly eroded democratic discourse in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the country where he was born, Australia.

The practice goes back centuries, of course. The upper crust, formerly known as royalty and religious leaders, has always eagerly claimed control over the means of communication. They derive their political power from influencing the very architecture within which the rest of us communicate and interact.

The continental Church, for example, assumed ownership over both Latin, which was considered the divine language, and the practice of writing, which was a monastic tradition consisting mostly of the tediously slow copying of other people’s words. With the introduction of the printing press, it became easier to reproduce and distribute text, ultimately resulting in the fragmentation of the European Heaven-verse.

So is Musk’s impulse buy a bad thing? Maybe. Probably. It can’t be much worse than it’s been as Twitter’s leadership watched and did nothing while bots and bullies frayed public discourse. But there is solace in the fact that after centuries of powerful people purchasing permanent mental real estate, even their deeds are ultimately impermanent.

At least now Musk’s perplexingly named son, X Æ A-Xii, has a better chance of passing that CAPTCHA test at signup.

On to this week’s update.

BIG READ: The big in-game ad debate

With the announcements of Sony and Microsoft looking into ads as another revenue stream, we’ve entered into a somewhat obvious discussion. Game journalists have predictably mocked and demonized the notion, despite depending on advertising for their own livelihood. Over the past two weeks, commentary has revolved largely around how terrible ads will be and how they will ruin games forever for everyone.

Another nuanced debate is here.

Today’s winner receives an all-expense-paid cruise to Azeroth

ICYMI, I previously covered ad-supported video games as one of several emergent categories. Across the board, the manner in which a group of entertainment companies makes money strongly impacts the type of content they produce. The design, development, marketing, and distribution of a $60 boxed solo campaign game are wildly different from a free-to-play multiplayer title. With the widespread popularisation of interactive entertainment, novel revenue models have become available and, increasingly, sustainable.

The posh notions of cultural critics are a historical cliché. When television rose to popularity in the 1950s, filmmakers snubbed their noses. Such low-brow entertainment was only for the lowest of cultural affinities and void of deeper meaning like movies. Comparing a blockbuster Hollywood production with a quiz show tells you more about the intellectual insecurity of the person making the comparison than the two different cultural artifacts.

Change is hard.

But such a shift and deliberate move into a new economic model doesn't occur in a vacuum. The acceleration in consumer adoption of digital services during the pandemic has brought about saturation perhaps faster than expected. Not only that, any gaming services now available compete directly with other forms of entertainment.

For one, this is a much broader conversation. Netflix, which got absolutely hammered last week because it lost 200,000 subscribers, is trying to remedy the same problem that, in time, most subscription services will face in two ways. On the one hand, it is trying to crack down on the number of users per account. Reducing the maximum allowed individuals, or password-sharing, will, they hope, encourage those banished spectators to get their own accounts. That’s rather aggressive, of course, and unlikely. All those ex-boyfriends still using your account or the empty-nesters left behind as the brood went back to college are going to have to fend for themselves. This means they’ll just stop watching or buddy up with a new benefactor.

On the other hand, it is exploring advertising as an additional revenue source. Soon enough we’ll hear about the democratization of content as Netflix and others will offer up a reduced tier of its catalog for free in exchange for adding interstitial ads and more aggressive product placement. More cynically, it’ll be a tax for the poor.

But Netflix’s circumstance should worry other digital platforms as well. Even as a first-mover, Netflix first managed to make a name by buying out a lot of long-tail, back-catalog type of content. Then, as the competition started to crystalize, it increased its content acquisition budget and launched exclusive series like House of Cards (remember that one?). Binge-watching became a thing and streaming platforms were everyone’s favorite. In the past few years, however, Netflix found itself forced to commit to the most expensive content type available: exclusive feature films. A slew of films headlined by yesteryear celebrities poured onto the platform, each hit offering a lesser high.

The comparison with video entertainment has its limits, of course. Online multi-player games manage to maintain their popularity because of the very strong network effects that occur when people play together.

Arguably, video streaming’s weakness vis-a-vis conventional television viewing has been the absence of synchronized spectatorship. The most valuable content categories in TV have always been news and sports because it encourages audiences to watch simultaneously. For major world events, we still turn to television for the sheer reason that we know we are watching it together with everyone else.

HBO Max, which of course wrote its rulebook in an era of more conventional viewing, has managed to leverage this principle well as it heavily marketed the start of a new Game of Thrones season or blockbuster release to both drive shared viewership in anticipation of Monday morning watercooler conversation (“Oh my god did you see last night’s episode? Khaleesi was craaaaay yo.”) and to drive subscriber numbers. (I swear that’s how my friends talk.)

Horizon Zero Dawn, brought to you by Kraft Mac & Cheese

One immediate difficulty in foreshadowing what an ad-based games economy looks like is the wide-ranging diversity of possible models. It is possible, for instance, that multiplayer games will feature interstitials and sponsored loading screens. Riot Games has already been experimenting with in-game banners showing advertising that are only visible to spectators and not players. Along the same lines, it is not difficult to conjure up the notion of sponsored events. Environments are entirely digital and therefore capable of facilitating all manner of aesthetic changes and ad integrations. It also raises questions with regards to targeting and protection of especially younger consumer audiences. Never mind that brand managers tend to scare away from the action and occasional violence. They need no protection. Creating a safe space for young audiences, kids, and really anyone else that deserves to be spared the relentless onslaught that manifests whenever a retail bank or insurance company deploys its marketing capital.

Another important piece that is often overlooked is the fact that consumers aren’t merely passive purchasers of goods and services. A large part of an average person’s spending contributes to a broader sense of oneself. Die-hard PC gamers don’t just build their own rigs. They also order customized mousepads and mechanical keyboards. Accessories go a long way in gaming as they do among car aficionados. My upstairs neighbor is a bicycle fanatic which means he has not one but six bikes, goes on special bike camps with his friends, owns an array of GPS trackers, and proudly prances about in his $88 Lululemon bike shorts like a sexy power ranger.

King of the ad hill

As for who will come out the victor, I expect Microsoft to be rather serious about its advertising ambitions. First, it acquired Mixer with the distinct intention to compete with its rivals Twitch (Amazon) and YouTube (Alphabet), which both make the bulk of their money from advertising. But rather than selling ads against content like a more conventional media company, Microsoft is better positioned as a digital layer that connects audiences with advertisers across different activities (play, work).

Second, Microsoft’s ad revenue recently broke $10 billion, according to its last earnings. Already in 2019, it renamed its ads business from Bing Ads to Microsoft Advertising and simultaneously acquired Promote IQ, a retail media ad tech company. Add the $300 million acquisition of Drawbridge, a cross-device startup, in 2019 and the 2021 purchase of Xandr (previously AppNexus) from AT&T, and we have the initial foundation of what may become a platform-agnostic digital ad network.

Third, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella spent four years overseeing a group that included search and advertising before taking the helm. I’m not saying it was the gravity point of the man’s career. But I am saying that he knows the ad space.

Sony, however, isn’t quite there yet. In terms of ad-related assets, it is woefully behind. Certainly, it holds several relevant positions. It sold GSN Network to mobile gaming maker Scopely for $200 billion in exchange for shares in the latter. Scopely recently raised a Series D financing round which valued the firm at $1.9 billion and included The Chernin Group, a media and entertainment investment fund, and Advance, a privately-owned company run by the Newhouse family that invests in media and tech firms. And Sony was part of a $20 million round in Anzu, which calls itself the “world’s most advanced in-game advertising platform.” The Tel-Aviv-based startup has been aiming to become the “first programmatic monetization platform that respects gamers.”

Over the course of the next few years, we can expect to see ads appearing where they previously weren't. As the reality of ad-based gaming quickly becomes tangible, the initial protesting from industry writers and gamers is understandable. It is also going to be drowned out as large conglomerates placate their needs for continued growth and competition over audience share. The time in which video games were so-called ‘pure play’ spaces, meaning void of any commercial messaging, is over. Does it really matter if the prize you're trying to win by playing is sponsored? Audiences have accepted the blending of creativity and commercials and literally every single form of entertainment. Offering an ad-supported subscription will is the next logical step for not just Sony and Microsoft but the broader digital entertainment market, whether we like it or not.

NEWS

Ubisoft’s rumored acquisition

France rallied this week with both the re-election of prime minister Macron, who almost lost against the far right-winger and friend of Putin, Marine Le Pen, and on Friday Bloomberg reported that Ubisoft may be up for sale.

Industry observers expressed criticism, arguing that it would be bad for the industry. The idea of a few large conglomerates owning and operating most of the major IPs in an entertainment category has seldomly won favor among consumers and critics. But one has to wonder what the long-term benefit would be of Ubisoft’s continued independence.

Last year it congratulated itself on implementing “profound changes to ensure the continued development of an inclusive working environment” even as an investigation by the French newspaper La Télégramme found that employees disagree. Among its findings, one-in-four employees reported either being victims of or witnessing harassment, and over one-third of people who reported incidents felt that management did not sufficiently support them.

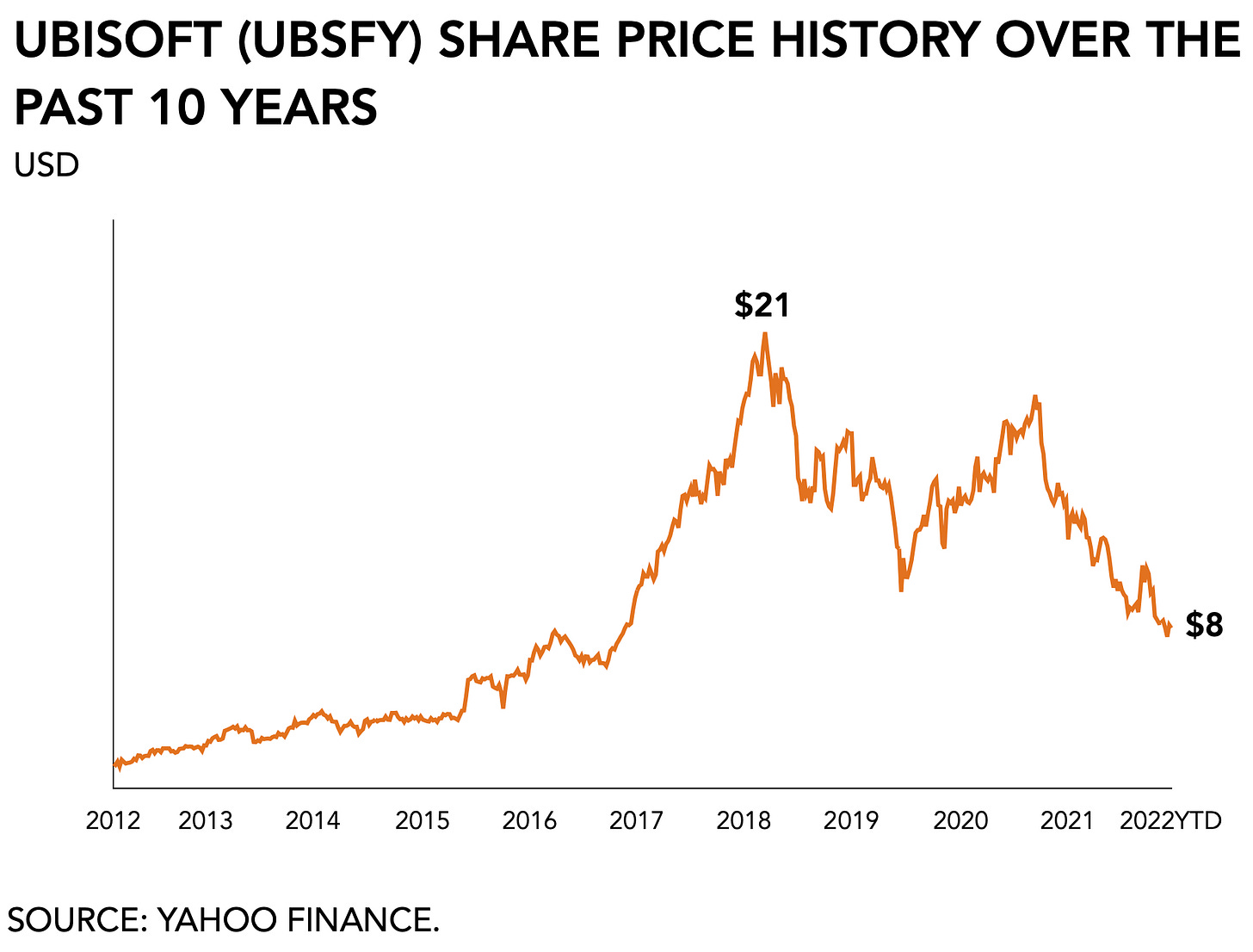

Meanwhile, Wall Street analysts argued that an acquisition by a private equity fund would not make a lot of sense unless it was at a high price point. Ubisoft’s difficulties to generate cash, which is currently expected to be negative, suggest a buyer would have to wait a decade to make a profit. That assumes Ubisoft manages to turn its economics around and achieve 30% profitability with its title catalog that has not delivered solid results recently (hence the lower market cap). It has also already pursued most available content deals with emerging cloud gaming services (e.g., Luna, Game Pass, Stadia), which means its short-term growth will have to come from delivering great new titles.

On Friday Ubisoft’s share price jumped +22% from $7.36 to $9.04.

Turtle Beach explores possible sale

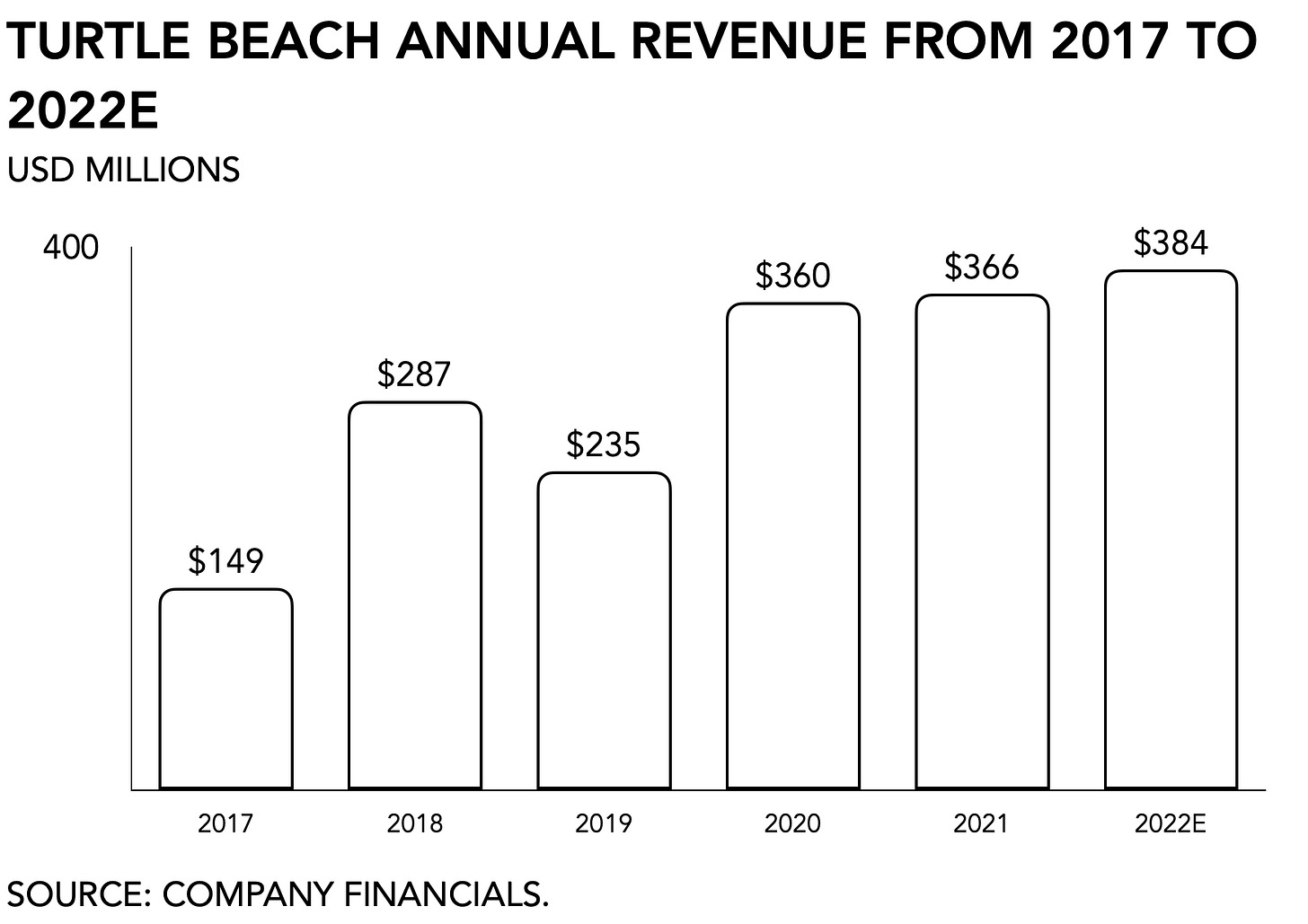

The business for gaming accessories isn’t getting any easier. In addition to the continued supply chain issues and increasing shipping costs, demand for high-end equipment is likely to soften in the months to come due to inflation, seasonal changes, and the return to pre-pandemic life.

Previously one proposed buyer, Donerail, a subsidiary of Harbert Fund Advisors an activist investment fund that holds 3.64% of Turtle Beach’s shares, withdrew its offer and moved to dispose of the firm’s leadership team. Donerail’s executives argued that the game accessory maker lacked open-mindedness and focus. Now Turtle Beach, which trades on the NASDAQ under ‘HEAR’, is exploring strategic alternatives, including a possible sale.

Arguably, headphones are a more critical hardware component to establish an immersive experience than VR headsets, custom keyboards or controllers, and gaming chairs. It explains why consumer demand for high-end headphones that can relay three-dimensional sound and facilitate crisp communication with teammates has skyrocketed from $1.7 billion to almost $9 billion between 2017 and 2022. Shipments of headphones roughly doubled from 286 million in 2013 to 549 million in 2020.

The category’s momentum is, in part, the result of Apple’s entry with the 2014 acquisition of Beats and the later release of its AirPods Max. Gaming headphones tend to offer a more comfortable fit and better communication than their fancier, luxury cousins. But the latter is also, on average, four times more expensive. It is probably why Donerail is trying to dislodge Turtle Beach’s current leadership team.

The headphone maker is scheduled to report earnings next week and forecasted a +5% revenue increase in its most optimistic scenario. Ahead of earnings started marking the stock down, as rival Corsair, too, warned about a slowdown in consumer spending for 22Q1.

PLAY/PASS

Play. Are you spending enough game time with your significant other? I bet you’re not.

Play. Is it Destiny 2 or real-life Mars in 8K?