The holiday season makes lots of people emotional.

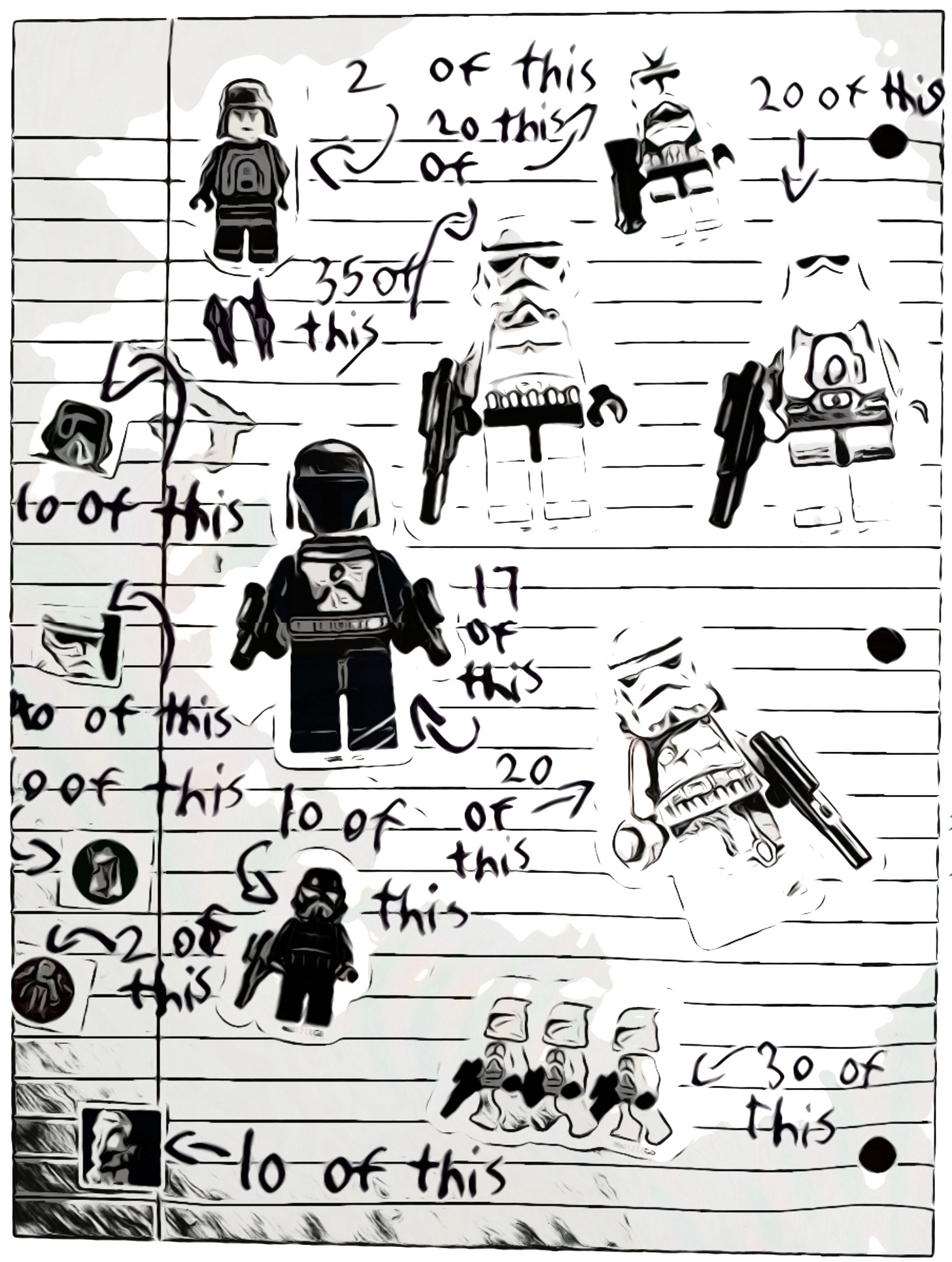

Here in Brooklyn, I’ve just wrapped the last of the LEGOs my 8-year requested for Christmas. It is the culmination of several months of painstakingly scouring the internet for specific Star Wars minifigs that he plans to use for his stop-motion animation.

I have been tearing up all day.

It’s not at the forethought of watching his happy little face as he opens each present.

I’m crying at the realization that, despite being made entirely out of plastic, LEGOs are really goddamn expensive. A Millennium Falcon with seven minifigs will set you back $800. The same for an AT-AT. An Imperial Star Destroyer? $700.

So much for themed set design. The kid is going to be using crayons and tape instead.

Even so, LEGO, the company, is doing rather well. Since 2003 when it sold $1 billion worth of tiny bricks, sales have increased seven-fold. Fueled by a host of adjacent media assets, including full feature movies and video games, and, of course, the pandemic, the block maker is one of the most valuable toy brands in the world today.

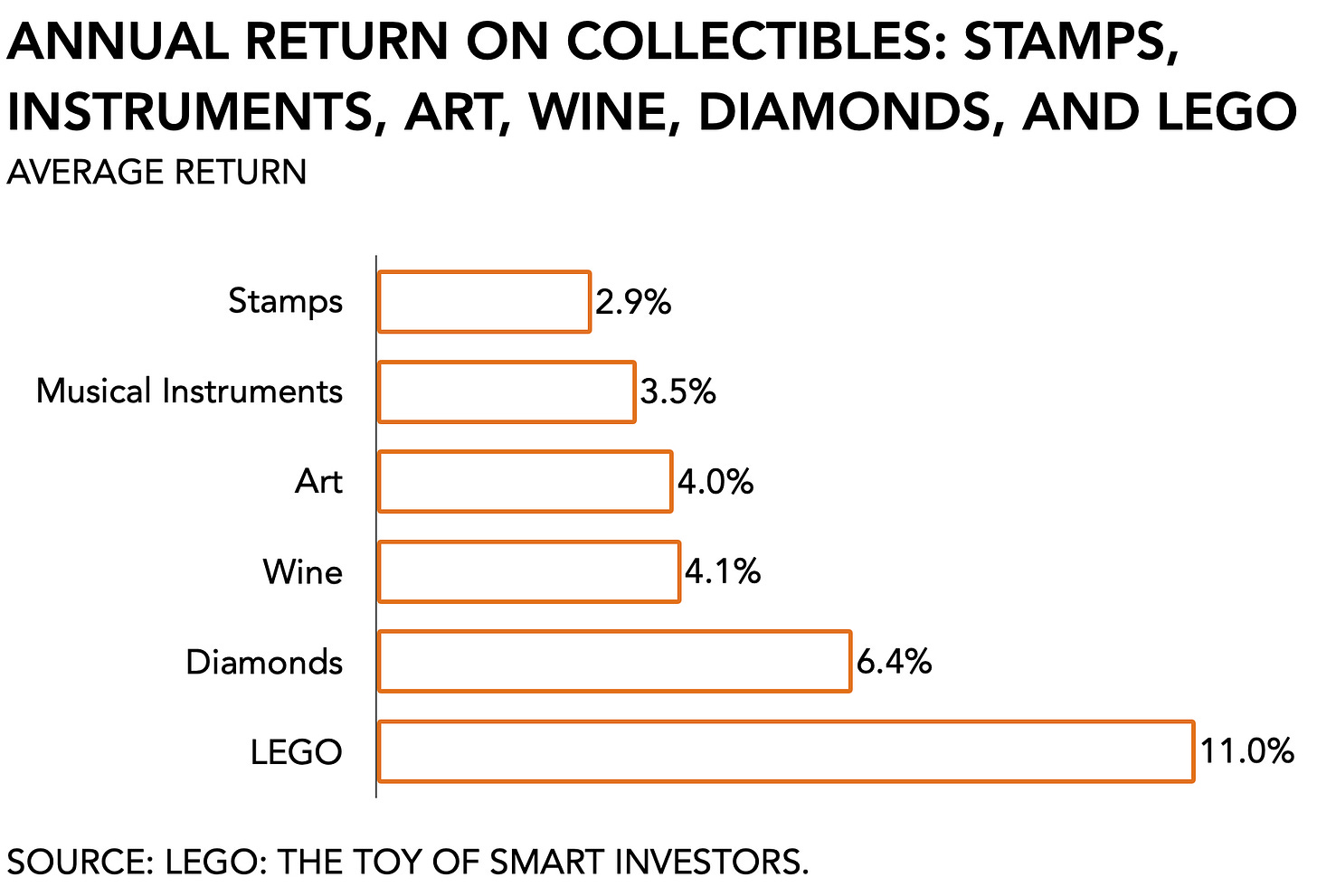

But what potentially makes the present financial bloodletting justifiable is that they also retain their value. According to a recent study titled LEGO: the Toy of Smart Investors, the tiny bricks have a higher return than other, more common asset classes. Based on a sample of 2,322 unopened sets across different popular themes, researchers found that the annual average return is about 11%. That is considerably more than other cash-intensive collections.

Similar to wine, non-use means LEGO sets increase in value. As more boxes are opened, the number of closed sets declines, and therefore their rarity and value go up. Next, different sets perform unequally. According to the researchers, small and huge sets are more profitable than medium-sized ones because the former often has unique parts or mini-figs and huge ones tend to be released in limited editions. Moreover, thematic content matters: “seasonal, architectural, and movie-based themes deliver higher returns.”

An important driver behind the value of plastic bricks is that LEGO presents a ‘system’ rather than a toy. Each set is compatible with others, and even if specific themes come and go, the native format remains roughly the same. It’s for that same reason you’ll find a bunch of my now vintage LEGO pieces mixed in with my kid’s.

Building a collection is key. Consequently, there exists a thriving secondary market with ample supply and demand. Beyond the obvious generalist sites like eBay where you can literally find the biggest crap ever and some real gems, there are also specialized sites to get that one authentic Queen Amidala minifig. (It’s $80 if you were wondering.)

The fractionalization of entertainment

The value increase of both LEGO the company and the blocks occurred during roughly the same period in which I spent a lot of time explaining to video game execs that the industry’s digitalization and subsequent introduction of micro-transactions would set off a prosperity bomb. They didn’t see it at the time. Instead, they argued that gamers would prefer to own physical copies above all else. And gamers thought so, too.

But both industry and consumers have largely moved on. The bulk of revenue in 2021 comes from digital sales, and people are more than happy to spend real-world money on digital in-game items, funny dances, hats, unicorns, and god knows what else. The digitalization of entertainment wasn’t a piece-for-piece transition of physical assets to an online environment. Rather it involved the fractionalization of entertainment that emphasized one’s own unique experience.

There are parallels with other hobbies. For years I played Warhammer 40k and Bloodbowl. To me, it centered on painstakingly assembling tiny figurines and painting them. I am absolute trash at playing but putting custom models together and creating a unique feel and color scheme is immensely satisfying.

The same goes for Magic: the Gathering. Ever since it captured me, it’s been hard to shake. My Exalted deck shines bright with aspiration. Whenever I feel the grownup world gets me down, I rip open a few booster packs to supercharge my inner child.

What LEGO, Warhammer, and Magic: the Gathering have in common is that their value far exceeds their material costs. These are complex worlds of interlocking, modular components. More so, my own fascination with each of these franchises proved foundational to the company we started a decade ago. One way to describe what we did at SuperData was explaining to decision-makers in video games why digital goods and virtual items would revolutionize their business. We’d describe the new in terms of the old. Plastic blocks, metal miniatures, and cardboard covered in ink were respectable predecessors that pointed to assembly, both of parts and people, as the most valuable aspect of play.

My wish for you this holiday season is that before you rip open that new set of LEGOs from Santa, you take a moment to consider its investment potential. Not in terms of monetary value, of course. But think of the wealth it allows you to share with that 8-year old impatiently waiting by the tree.

Happy Holidays!

NEWS

Dang, Embracer. You tryna buy errbody.

Within the same breath, European game conglomerate Embracer told us this week that it is acquiring Perfect World Entertainment and Dark Horse. This comes within days of the announcement of its acquisition of Asmodee.

As for business rationale, we don’t really have to guess here. Using the abundance of cheaply available capital and low-interest rates, Embracer has accelerated its buying spree from a focus on video games to now also include adjacent entertainment categories such as board games and comic books. Cross-pollinations, or transmedia potential as Embracer likes to call it, are the media equivalent of synergies. Clearly, it intends to leverage its distribution network and have everyone work together as one big happy entertainment family.

There are a few concerns, however. First, buying lots of different medium-sized organizations creates paperwork and back-end chaos. Getting this growing consortium of creatives to work together nicely and efficiently is going to be a challenge. That can prove more difficult than a ferocious M&A crew can model in excel.

One historical example is the case of Hasbro Interactive which went on a buying spree in the late 90s. It went from zero to one billion dollars rather quickly at a time that such an amount was still considered extraordinary. However, its ambitions got the better of it as keeping the different divisions on the same page proved impossible. When the market turned, Hasbro Interactive lost its momentum and was sold for parts.

Times have changed, of course. But Embracer did proudly announce that it now has no fewer than 86 internal game development studios, employs over 9,000 people, and operates in more than 40 countries worldwide. Good luck sending everyone their holiday basket.

Second, mixing different colors too quickly always runs the risk of ending up drab. As other publishers are formulating a specific identity or lead with a single franchise (e.g., EA leads with sports, Activision Blizzard focuses on Call of Duty), Embracer is within striking distance of becoming a clearinghouse of mediocrity. What, exactly, is the firm’s core identity here? In a sea of digital content, a clear brand promise helps distinguish you from everyone else. It’s not immediately obvious to me that Embracer has spent as much time detailing what it is about as it has been brokering deals.

But those concerns are for later. Right now we’re witnessing the emergence of a new European powerhouse that is more valuable than Ubisoft or CD Projekt. That’s a firm embrace.

Rec Room raises $145 million

With a $3.5 billion valuation, Rec Room has almost tripled in value since its previous round in March. The basis of all this excitement is the increase from 2 million people “playing and creating content” to having “enabled over 37 million people around the world to connect and create.” I’m unsure what “enabling” here means.

It’s also not immediately obvious how those numbers were sourced. Granted, it’s a moment to celebrate but its press release comes off rather insecure.

“In August, Rec Room launched on Android, making the immersive world available to Android's +2.5 billion users.”

Yes, you and every other app that launched the last few months. How does that make you different?

Given the current enthusiasm around all things metaverse/creator economy, Rec Room is well-positioned to make the most of the momentum as we’re headed toward another lockdown. And, in honesty, it’s a fun application. Let’s see if it holds water once it starts publishing some real numbers in an S-1, for instance, that we can compare to Roblox. Until then much of the excitement originates in Rec Room being an obvious acquisition target for Meta. The more pertinent question now is: will Zuckerberg buy or build?

Investor confidence in Activision Blizzard is starting to slip

In response to the growing turmoil at ATVI, Wall Street analysts have started lowering their expectations and subsequently the firm’s anticipated target price. Turmoil in its talent pool is causing “waning confidence” among analysts, who feel that the publisher first has to deal with discontent before it can steer the ship back in the right direction. Among other things, Activision Blizzard is trying to fend off unionization and faces delays among several of its major franchises. Its shares have lost -29% in value TTM compared to S&P500 which is up +27% and its valuations are trending near five-year lows.

SuperGiant wins Hugo Award

After the British Fashion Council created a new award category to include a fashion award for metaverse design to improve its relevance and appeal to younger audiences, more were likely to follow. This week, the Hugo Awards, an annual literary award for the best science fiction or fantasy works, picked a video game for the first in its history. That’s exciting and, in the case of Hades, well-deserved. The game offers a fresh take on familiar Greek mythology and re-tells a story of love lost, death, and rebirth in a way that books and film cannot.

More generally, adjacent entertainment categories and creative industries have started to recognize the talent currently employed to make games. Holding the talking stick that makes a young generation of consumers listen, means that other creative industries can choose to either ignore or understand. Expect more award organizations to do the same.

PLAY/PASS

Pass. And speaking of esports, the NY Times ran a hokey article on “e-sports” as it called it. Because it forgot to include literally anyone from the industry and instead relied exclusively on sources from traditional sports.

Play. South Park’s commentary on NFTs. It’s funny. And it tells you mainstream adoption isn’t far out because you can only make fun of something if everyone knows what you’re talking about. Like that time SNL made fun of esports.