Book review: The Metaverse and how it will revolutionize everything

A treatise on the next internet and its shortcomings

TL;DR Matthew Ball manages to capture a distinct moment in the history of technological progress, its flaws and promises, without succumbing to idealism.

What follows is a review of an early copy of the book, a general critique of the popular understanding of the Metaverse, and comments from a recent conversation Matt and I had in the lead-up to the book’s release. Since it’s a bit longer than my usual write-ups I’ve cut it up into a few sections.

A bit about Ball

In 2020, Matthew Ball, an investor and the former Global Head of Strategy at Amazon Studios, suffered the unenviable task of having to predict the future of everything.

After publishing a series of essays outlining what he believes to be the likely next iteration of the internet, Matthew Ball’s writing has quickly become canon among tech investors and entertainment execs. And now his book, The Metaverse: And How It Will Revolutionize Everything, offers an elaboration of the central tenets of what’s to come. Fueled by the sudden and enormous attention for the concept among leading technology firms and brands, Ball finds himself the de facto thought-leader on the Metaverse. As he tells it: “I was very surprised by the popularity of the term.” And now the world wants to know what’s next.

For the sake of this review, I should first disclose my existing connection to the writer. As a colleague and confidant, I’ve come to know Matthew as a well-read and humble observer of tech and entertainment. Different from the fist-pumping bros that generally inhabit such industries, his perspective is cynical enough to be believable and sufficiently seasoned to be useful. Far from offering an exuberant read on the future, Ball thinks and writes in an exact and careful manner. Finding myself regularly explaining his theories in classrooms and boardrooms, I consider myself equal parts collaborator, critic, and correspondent.

Five decades of talking about media technology

Before diving into the work in detail, it is secondly important to properly position the book in a broader dialogue on the relationship between technology and society. The Metaverse and its promise are a continuation of a long-standing conversation about the role of media technology in everyday communication, the organization of information, business practices, education, and political engagement, and how it, in aggregate, impacts the character of society.

Ever since the introduction of silicon chips in the 1970s, most thinkers on the topic have conflated a change in technology with progress. And for good reason. After centuries of the small-minded burning libraries and banning books, digitalization—the combination of storing information in a digital format and distributing that information seemingly ad infinitum via online networks—would finally allow building on the past’s wisdom, experience the human condition in high definition across time and space, educate the many to bolster everyone’s quality of life, and ultimately act in our collective self-interest. Insert cynical comment here.

Nevertheless, this conversation has been going through a few successive stages. Emerging as an industrial invention, much of the initial curiosity centered on how microprocessors impacted production processes and the economy at large. Like the steam engine and mechanized manufacturing, the microchip sits at the foundation of an economic transformation. Writers and analysts described how it would ring in a third industrial revolution and deliver us to a ‘leisure society’ where we’d only work some of the time. In our lifetime we would witness a ‘New Renaissance.’

Following, the focus shifted to consumers. In the 1990s the “information superhighway” gave access to an exciting new future where information was no longer scarce and available to all. Cyberspace and virtual reality became hallmark terms to describe the imminent changes to social interaction, leisure, and work. It was during this decade that sci-fi novelist Neal Stephenson wrote Snow Crash and coined the term Metaverse. From now on, civic discourse would occur in “electronic agora.” United States vice-president Al Gore promised “robust and sustainable economic progress, strong democracies, better solutions to global and local environmental challenges” among other things. Microsoft founder, Bill Gates, postulated broadly about “friction-free capitalism.” And Nicholas Negroponte, the architect and founder of MIT’s Media Lab, painted an exuberant image of what it would be like in the inevitable future, arguing that “previously impossible solutions [would] become available.”

Interest-based networks dominated the conversation in the early 2000s. Wired magazine’s editor-in-chief, Chris Anderson, published his famous book on the long-tail, arguing that even scattered audiences would manage to find each other across networks and make niche content financially sustainable. First dial-up and later broadband allowed mainstream consumers to access the internet from home to shop, socialize, and play. Interactive entertainment started to reach millions and fringe activities like online multiplayer games evolved into billion-dollar franchises. With the arrival of Facebook, we had successfully achieved the realization of another one of those exciting euphemisms, the global village.

The popularization of the smartphone and the way it reconfigured how most accessed the internet set the tone for the most recent wave in techno-enthusiasm. It proved disruptive to existing industries like telecom providers, handset manufacturers, and content creators, and, subsequently, immensely profitable. After five decades of economic and social transformation, new technology and its anticipated impact have become synonymous with growth and prosperity.

For our current epoch, Ball refurbished Stephenson’s Metaverse to serve as the next theorem to describe society’s relationship with information, communication, and expression. It has quickly gained favor among large tech firms that use the concept to rally their next innovative push for products and services. Now imagined as a three-dimensional, persistent universe that can be accessed by millions at once for a broad array of activities, the Metaverse is the latest conceptualization in a long-standing tradition that uses equal parts science-fiction, spatial metaphors, and exuberance to ponder our technologically mediated future.

Matt’s mapping of the Metaverse

It is no coincidence that such eager excitement about the next internet emerges during a global pandemic. While in lockdown, hundreds of millions of people experienced first-hand what it was like to work from home, go to school remotely, organize anything from wine tastings to Dungeons & Dragons night via Zoom, and attend birthdays and funerals from afar. As part of its viral load, Covid-19 destigmatized spending time online and normalized a broad array of novel behaviors.

Timing is equally important for several of the Metaverse’s most vocal evangelists. Zuckerberg betting on the farm and changing the course of his entire organization is a full-scale commitment he beta-tested when buying VR headset maker Oculus. Unclear on whether there was a there there back then, many now, too, hope Facebook’s CEO knows something they don’t and followed into the fray. Facebook’s public transformation to become Meta and claim its stake means the frenzy has become inescapable.

Already researchers are postulating big changes ahead. Gartner forecasts that by 2026 at least one-in-four people worldwide will spend an hour each day in the Metaverse for digital activities including work, shopping, education, social interaction, or entertainment. It also predicts that 30 percent of global businesses will have products and services ready. It is to be a revolution from the top down.

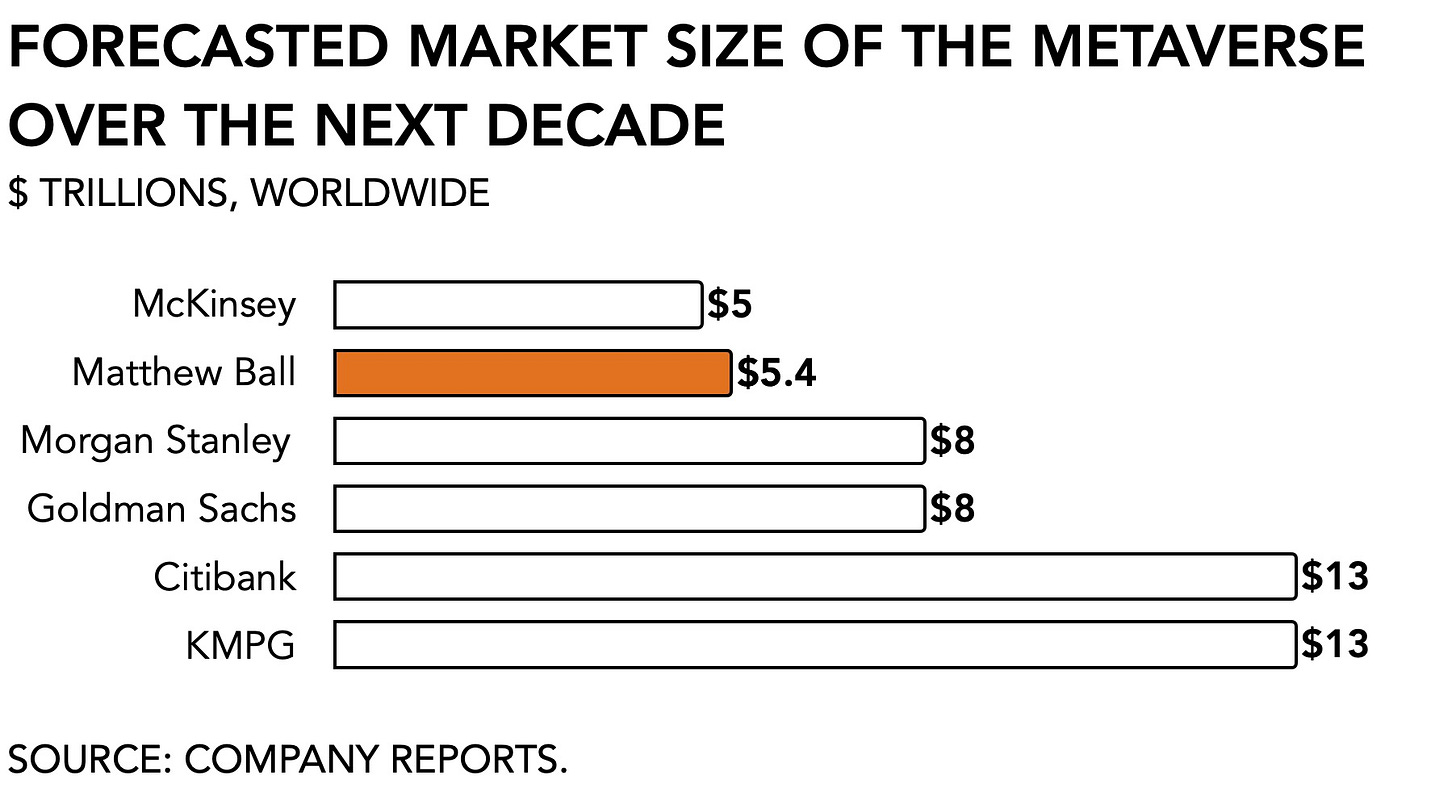

The research divisions from several high-profile banks have been quick to release their forecasts, ranging from $5 to $13 billion over the next decade. Naturally, the financial research industrial complex is keen on bilking a sincere push for improvement, even if we run the risk of misreading the tea leaves. It puts a lot of pressure on Ball’s book, which arrives at a time when excitement runs high, but answers are few. He explains:

“The book is the culmination of working with some of the most prominent firms in the space and getting to regularly talk about what we want it to be.”

Over the course of 352 pages, the work connects the next possible version of online life to historical precedents like the printing press, electrification, and the iPhone. Succinctly, Ball argues how each of these advancements changed daily life by providing new ways for people to express themselves, share information, and transact. In fifteen chapters that are roughly based on his earlier essays, Ball expounds his ideas and throws ample amounts of cold water on eager expectations. When I ask him about the $5.4 trillion forecast, he refuses to commit himself to the number and says to be merely walking “through the exercise of understanding” by modeling the Metaverse to account for an approximate 15% percent of the digital economy in ten years. Anyone claiming otherwise is a charlatan.

At the heart of his assessment are several key areas that he believes will need to advance to varying degrees in order to realize the Metaverse: networking, computational power, interoperability, payment, hardware, and blockchain. Anticipating an acceleration and expansion of each, Ball argues, will result in the next generation of the internet. But each is developing at its own pace and faces its own challenges.

The successful interplay between different industry segments will amount to a foundation for what’s to come. Like the iPhone, Ball explains, several distinct technologies had to advance and come together to facilitate the disruption it became. In that sense, the work presents a detailed and better understanding of the way in which technology itself changes and impacts daily life than is generally offered by writers of his ilk.

Ball’s persistence in pointing to the smaller often ignored steps that we will have to take is a welcome addition of nuance in the broader conversation about tech, finance, and entertainment where exuberance reigns perpetually. He does not sugarcoat the challenges ahead and argues that the necessary computing power is well out of reach (by a factor of 1,000), how segments like payment are frustratingly slow to evolve, and that the underlying hardware problem is “faaar from solved.”

Well-informed and detailed, his analyses offer a high level of scrutiny on relevant technology areas, their drivers of change, and their ultimate role in what is to become the Metaverse. Ball switches seamlessly from a conversation about online gaming and key improvements in graphic capabilities to an analysis of back-end infrastructure and latency improvement. By doing so he reminds us of the very long road ahead.

In his conclusion, Ball confidently states: “I am certain about much the future,” before rattling off a list of technology truisms (e.g., latency will improve, young people will adopt first). As a tech investor, he wisely anticipates the current hype cycle as part of a long evolutionary process. But rather than claiming to know what’s to come, Ball closes with the observation that, ultimately, we are but spectators to a phenomenon that is both out of our hands and about to change our lives forever.

Infinity stones, one and all

A common problem in writing about technology is that the subject matter is likely to have changed by the time your book is out. Among the key tenets that Ball identifies, several are already struggling. He offers an insightful look into payment rails, for instance, to explain how the successful facilitation of financial transactions sits at the center of the widespread adoption of novel technologies. Credit card companies and other payment facilitators concern themselves mostly with product innovation to capture the largest possible share of overall transactions. However, they are often no more than slightly cooler storefronts for old financial institutions that add little to the experience outside of encouraging consumers to spend more and more frequently.

No amount of technology insulates this sector from common market challenges and poor leadership. Once considered a dominant force in online consumer transactions, Wirecard, a German payment processor and financial services provider, collapsed following an investigation by the Financial Times. The firm’s valuation dropped from $27 billion at its peak in 2018 to zero when it was delisted on account of widespread fraud. So, too, did Klarna, a Swedish Buy-Now-Pay-Later fintech firm, give new meaning to the term down round when its most recent investment valued it at $6 billion, down from $46 billion earlier in the year.

As for the software that is going to facilitate this digital worldbuilding exercise, several important questions remain. A month earlier, I had the good fortune of sharing a cab ride with Refik Anadol, a well-known digital data artist. He and his team build large-scale digital installations and multimedia experiences that offer a glimpse of a fully immersive virtual environment. (The image at the start of this write-up is one of his latest works that was part of the Let’s Get Digital! art exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence.)

When I asked Anadol about the recent release of the Unreal Engine 5 (UE5), a software engine used to generate virtual worlds and critically important to Ball, he replied: “UE5 is a dramatic increase of what we as digital artists can do.” To creatives like Anadol, the tools that help realize a vision are becoming more readily available and powerful.

Nevertheless, the momentum isn’t quite there yet. We learned from its high-profile legal dispute with Apple, that the maker of UE5, Epic Games, generates the lion’s share of its income with games like Fortnite ($3.8 billion in 2019) and that its engine accounts for a mere $97 million, or about two percent of the total. More recently, Unity, another publisher of world-building software, saw its share price drop of -74% in the first half of 2022, which was more than triple the decline across the S&P500, and consequently announced it had laid off about 4 percent of its staff. As the two leading players in this category, Epic Games and Unity are expected to deliver some of the critical technical underpinnings, but currently seem to lack the necessary economic stamina.

Next, hardware and computing power are two obvious pieces of vital infrastructure. And both are suffering from supply chain issues.

Makers of devices that would allow average consumers to access the Metaverse have difficulty keeping up with demand (which is good) but this will invariably increase prices (which is bad). The pandemic’s impact on the ability of consumer electronics manufacturers to deliver and ship their wares to buyers is likely to last for some years. They face an increase in the cost of shipping containers and a supply chain that is simultaneously undergoing an important market correction as labor has become scarcer.

Computing power, and specifically the semiconductors necessary to facilitate it, are having an equally bad time. A shortage in microprocessors combined with an increase in prices is depressing economic growth in the United States. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen stated that “a third of U.S. inflation is new and used cars and…it all due to a shortage of semiconductors.” She further called the shortage both “a national security issue as well as an economic issue,” in arguing for additional investment. Arguably these problems will be resolved in the long term. But given the Metaverse’s experimental stage, contemporary obstacles weaken the prognosis, and any anticipated effort to improve this circumstance will prioritize existing industries.

Finally, blockchain, which Ball says isn’t a central tenet, is having a really bad time, too. Ball offers an array of different perspectives on the financial novelty, ranging from an outright scam to a requirement for the Metaverse. As such he does not provide a satisfying answer to whether or not blockchains are really all that necessary or which protocol will reign supreme. When I asked him why he remains in elusive on the blockchain, he tells me that

“rather than taking a strong position, I felt my job was to explain everything known, unknown, and debated and make it available to everyone.”

Fair enough. It returns the onus of the Metaverse to the reader instead of providing a clear-cut answer. He does, however, allude to the fact that ownership of digital assets will play a critical role in establishing the Metaverse in the long run as it does more imminently allow gamers to carry virtual items from one application to the next while improving the challenges around revenue loss between publishers. Ball argues this will ultimately benefit interoperability which is a critical piece of what’s to come.

It is easy, of course, to pick off components in a theory about the future by citing current events. But we can, however, identify recurrences from previous tech cycles and take a more discerning stance.

For one, the way corporations talk about it confounds a sense of inevitability. Firms that regard themselves as pioneers in the new frontier tend to quickly inundate their corporate filings and press releases with the new vocabulary. It is something we’ve seen before. When the former CEO of Electronic Arts, John Riccitiello, took the helm at Unity, he threw his full weight behind the coming of virtual reality. Similarly, Microsoft fenced with its Hololens, HTC and Valve partnered on their headset, Google announced Cardboard, and Sony rolled out the PlayStation VR. Hundreds of other firms jumped in developing their own hardware components or software in the hope of claiming some of the burgeoning markets. Today, well over a decade since Palmer Lucky designed the first Oculus prototype and despite its many advancements since, virtual reality remains, in fact, quite evitable.

Next, the push toward the Metaverse is the new space race. It implies that global conglomerates should either be building their own rocketships or plan to be left behind. It allows us to determine which organization is future-proof and capable of navigating the new universe. Measuring a broad array of companies from different industry sectors by using the same qualitative benchmark simplifies things greatly and conveniently arranges a heterogeneous collection of economic agents toward a single purpose. Key to the rhetoric advocating the next Big Thing is rendering it into a spectacle.

The Metaverse is also pregnant with promises of a return to better times by moving forward. We are to experience musical performances together with millions of strangers in virtual environments. Online education will allow for lively discussion and interactive experiences rather than the dry transfer of knowledge. Commerce will bloom as our digital avatars can ‘try before you buy.’ Hybrid work promises a better work/life balance. It fits seamlessly in a much longer-standing tradition of projecting a romanticized idea of how things used to be into the future.

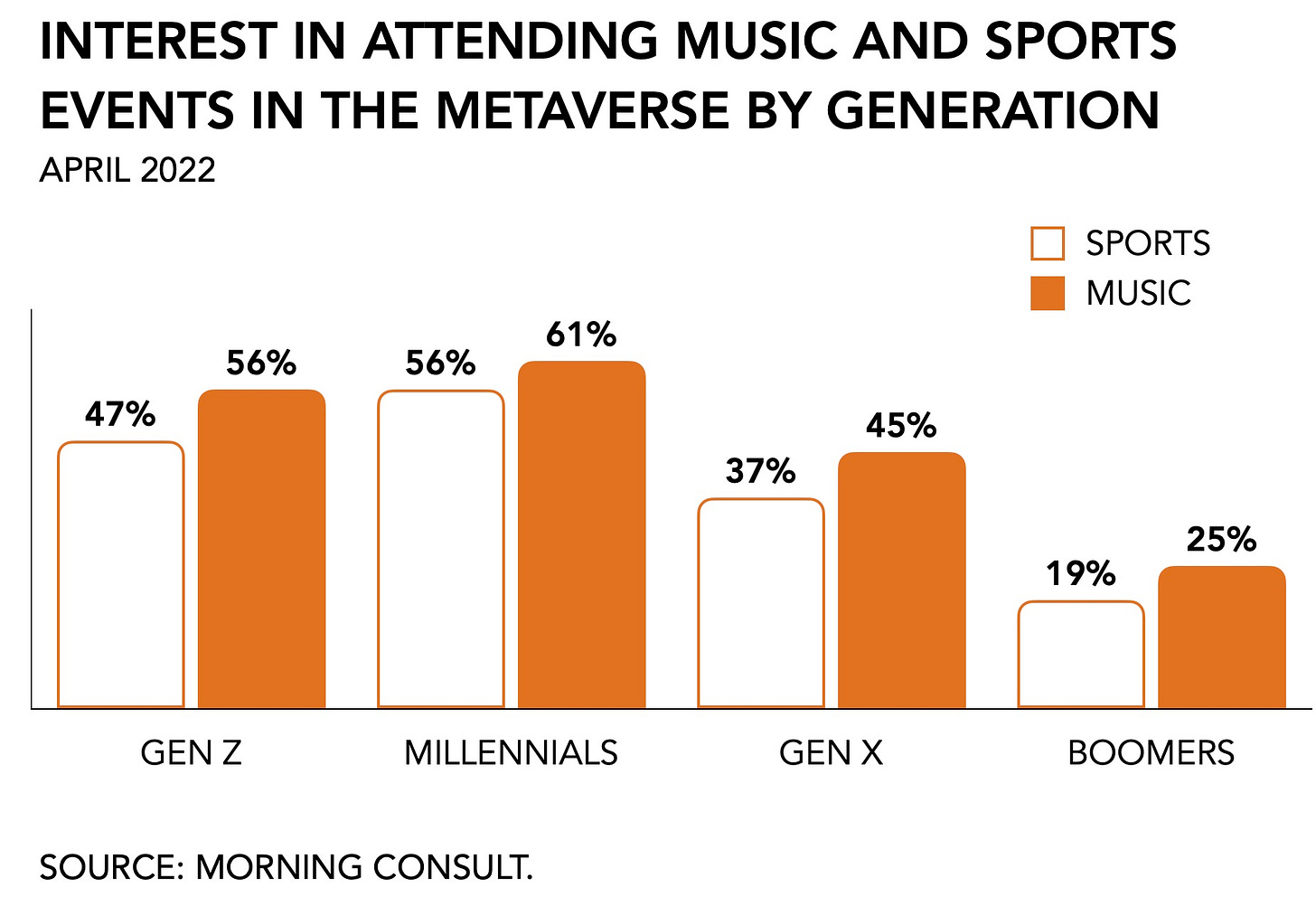

It is closely related to the idea that younger consumers will form the initial userbase. As Ball sees it, “Fortnite has sold, in each of the past four years, more in virtual apparel than some luxury brands.” Total spending on luxury personal goods will gravitate toward Millennials and Gen Z, according to a study, and will account for $286 billion, or just under two-thirds of the market in 2025. Connecting with this demographic will be critical to success, of course, and the appeal of virtual concerts and sports in the Metaverse is widely regarded as the way to reach them. Another study disputes this logic, however, suggesting that Gen Z is already showing a decline in interest.

Such discrepancies likely result from early volatility. Even so, many of the firms dedicating themselves to the realization of the Super-Internet are, despite their PR efforts, not exclusively doing so out of the kindness of their hearts. Money needs to be made. That means demand is another important aspect to the long-term equation.

A final similarity is an emphasis on how tech impacts society, but less so vice versa. Technologies and the investments and policies that enable and encourage them are often deliberately seeking to exclude or privilege specific groups of people. Electric cars are demonstrably better for the environment than those running on fossil fuels, but government policy continues to frustrate a more urgent rollout. The same applies to media technology. To presume the Metaverse to be an equally accessible space that is fundamentally neutral would be a mistake. Or, as Ball asks me:

“What will the Chinese Metaverse look like?”

Where he and I differ the most is in areas like education and employment. His enthusiasm for classrooms that will not just allow students to visit, say, ancient Rome, but learn about it by building it virtually is admirable. It is also naïve. There are preciously few school programs available around the world that have the necessary financial resources. Such an application would most likely be reserved, as it has been historically, for the best-funded educational institutions and well out of reach, again, for average students. That is not to speak of the broader politicization of classrooms in major economies like the United States.

Ball tells me that it is a “positive” that remote education will ultimately become significantly cheaper. But it reminds me of when the Federal Communications Commission assigned specific frequencies in the 1950s to establish instructional television. The hope then was to provide education at scale and low cost, but one would have a hard time today arguing in favor of the educational power of TV. Perhaps I’m too cynical and too privileged. I just don’t see it.

On the issue of employment, I have been a long-standing proponent of remote work. Both in my own experience as a founder and as an advisor to a remote work software provider during the pandemic, there is ample merit to the facilitation of novel working conditions. Nevertheless, any anticipated surge in productivity for, especially, office workers in the Metaverse is ahistorical. Even if the pandemic gave the impression that everyone would be working remotely, that illusion is quickly disappearing now that a growing number of corporations started to obligate workers to return. But perhaps some modicum of labor will take root online, allowing people to negotiate a hybrid model using virtual meeting spaces as proposed by Microsoft and Meta. Even so, historically the transition of workers into online environments has mostly resulted in the disappearance of jobs held by young people, women, and minorities.

Ultimately, the book covers only a small part of a much larger vision of what our day-to-day experience in the next decade could look like without falling to the allure of romanticizing it. Ball’s exposé doesn’t pretend to hold the answers for social scientists, politicians, or parents, but instead focuses on what he does best: providing a more nuanced understanding of the world to capitalists and tech entrepreneurs. And, having built a career both in academia and in business, I’d reckon that those that would otherwise fall outside of his usual audience will find the book well worth their time.

Outro

The Metaverse represents a need for more widespread collaboration and more elevated debate on the role of technology in society. The myriad of issues we’ve suffered over the last two decades at the hands of governments and corporations seeking to push their interests are in desperate need of an overhaul. Generally, we’re not supposed to ask critical questions whenever the next technological wave starts to manifest. However, the suffix ‘meta-‘ implies that we should know better this time. Based on our experience of previous transitions, the Metaverse cannot exist unless we ask questions.

According to Ball, the future of the internet is unlikely to solve the many problems around toxicity, data rights, and security, we face today. In fact, it “will make it worse, because many of the lessons won’t apply.” It is for that reason, he says, that

“we must fundamentally rewrite the suite of underlying protocols to provide more equitable ownership and set up for better outcomes.”

That’s a tall order. But Ball finds evidence in organizations like Epic Games whose CEO, Tim Sweeney, has been critical of data collection, advertising, platform power, and the lack of user rights for years. He also mentions Meta, which uses OpenGL and WebXR for its Oculus and shut down its auto facial recognition system.

It leaves us with a hopeful prognosis. Ball’s book is undoubtedly going to be considered the seminal work on the Metaverse. What attracts me to the work personally is that unlike the naïve enthusiasm held by writers before him, Ball comes at the topic from the trenches. He’s not here to mansplain the next internet but generously gives us the benefit of his access and experience.

We’ve seen how technology can fail us and, in turn, how we fail it. It is up to us to break the cycle of repetitive rhetoric and take on an active role in shaping a future that accommodates more of us. Start here.

Extra credit

For further reading, I suggest (1) Who owns the Metaverse, (2) Fashion’s Metaverse moment, and (3) A better-verse. Comments welcome.