[I’m on my way to Austin for SXSW. Hit me up if you’re there and come see my talk!]

In Brooklyn, the so-called Spring of Deception has just ended, and we have arrived at the Third, and final, leg of Winter. To give you an idea of what that’s like: yesterday it was 70F/20C and today there is snow.

Change, of course, is the only reliable constant. It presents us with the opportunity for continuous renewal. So, too, in the business of games. This week several senior figures from Activision Blizzard learned that their actions, or rather their inactions, had not gone unnoticed by everyone else.

And for good reason.

Despite having previously expressed some doubt as to whether or not the industry would still care about the growing list of workplace toxicity at Activision Blizzard, I’m starting to see seasonal change. Not in the least because the list is growing longer and darker. This week added a wrongful death suit by the family of a former finance manager who was found dead at a company retreat in 2017. Jesus.

In the final throws of winter, the embattled publisher is starting to get iced out by industry partners. First, Bobby Kotick will not be up for re-election on the Coca-Cola board where he has served since 2012. Predictably, he now claims to be too busy running his own company. It raises the suggestion that his inability to deal with workplace toxicity was, in part, the result of his extra-curricular activities. Um, okay.

Second, the SXSW conference organizers uninvited Activision Blizzard’s chief marketing officer, Fernando Machado, stating:

“Given the ongoing and unfolding nature around the sexual harassment accusations being covered up at the executive levels of Activision, we decided it was best to not have high-profile speakers from Activision present at SXSW this year.”

At last, a taste of what it’s like to be excluded and full-speed slam into that glass ceiling. A small step, certainly, but it carries the promise of spring and brings us one day closer to the industry’s climate change we really need.

On to this week’s update.

BIG READ: Gaming’s great convergence

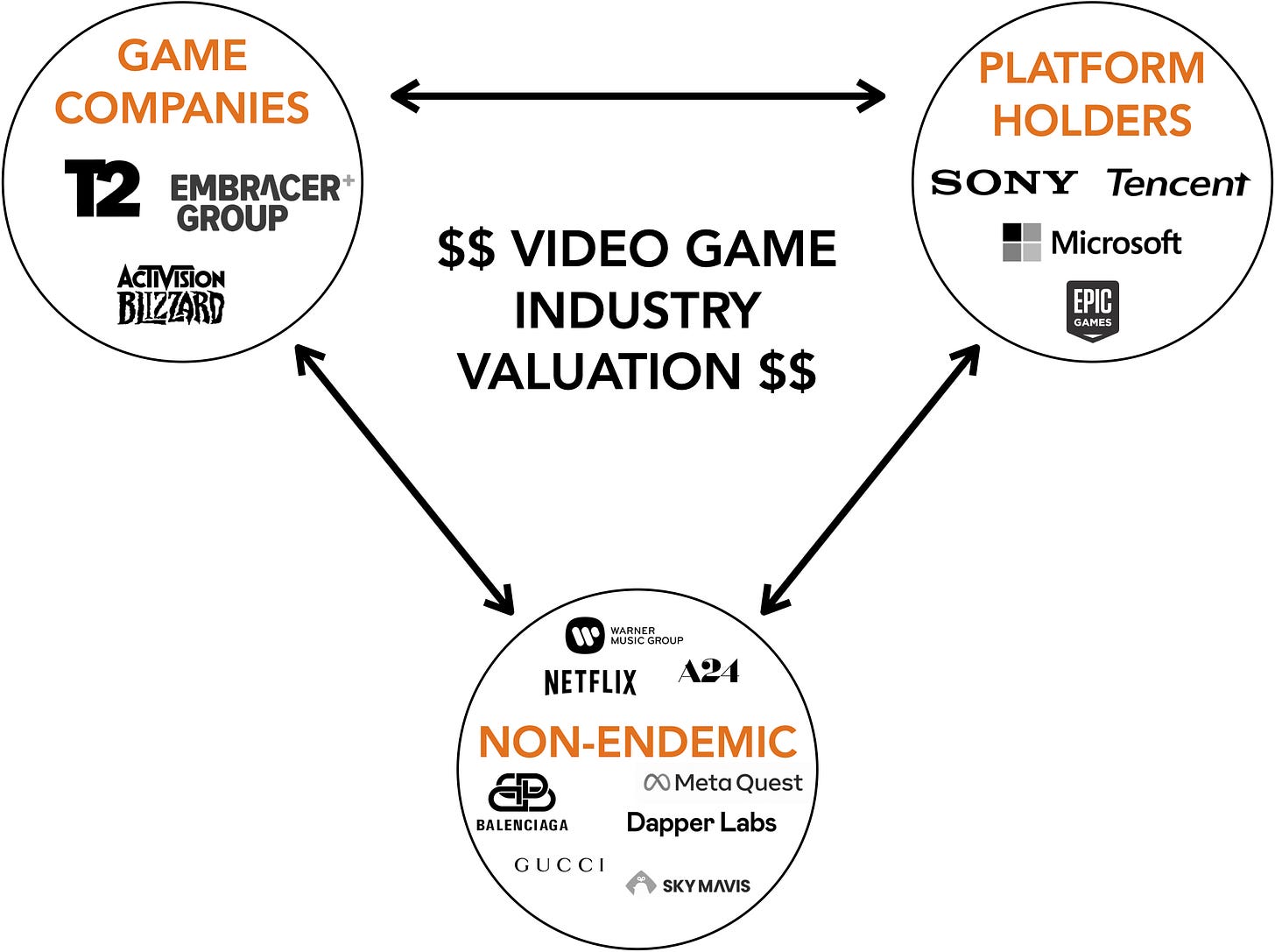

After several spectacular years of growth, interactive entertainment is teeming with cash, creativity, and confidence. The question that is starting to emerge, however, is: where to next?

First, publishers have been eagerly looking to diversify their portfolios. Their dependence on the blockbuster successes of their major franchises--NFL Madden, Grand Theft Auto, Call of Duty--pushed them to diversify their portfolios. And so they have. Activision Blizzard acquired King Digital to expand its addressable audience, and most recently Take-Two followed up on two earlier mobile acquisitions (Social Point and Playdots) with the $13 billion purchase of Zynga. They have also ventured further into more mainstream content development than ever before as evidenced by the release of the World of Warcraft movie and the announcement of an adaptation of Bioshock earlier this month.

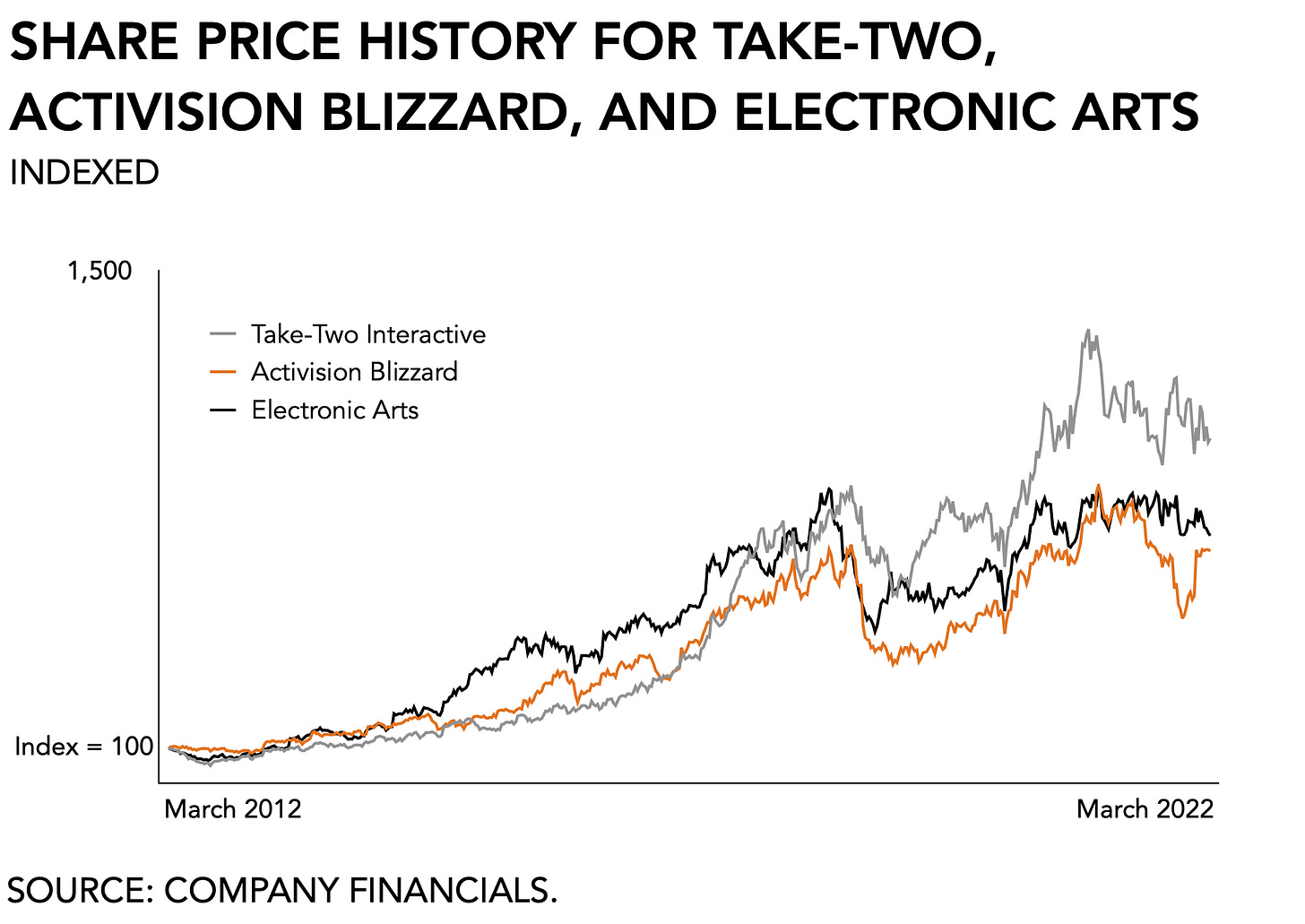

The growth of the top US-based publishers has been formidable. A decade ago, Take-Two traded at $15; today its share price hovers around $160. Activision Blizzard’s share price increased from $12 to $80, and Electronic Arts grew from $16 to $125. On average, these game makers increased eight-fold and outperformed the S&P500 which roughly tripled in value during that same period. Not bad for a niche entertainment industry.

Platforms, as the second group of industry protagonists, have started bulking up. Apple, keen on growing its service-based revenue, invested around $500 million in its Arcade service and continues to foreground its growing gaming prowess during announcements and product releases. Its effort pales in comparison to Microsoft’s recent $69 billion acquisition of Activision Blizzard, but with $14 billion of annual revenue coming from mobile games, Apple and its ilk have a vested interest.

Other, well-funded firms are trying their luck to evolve into platforms. In particular, Epic Games, which is valued at $42 billion, has been eagerly gobbling up new assets to jumpstart its flywheel. Ranging from the $35 million purchase of Houseparty in 2019 to the recent purchase of Bandcamp, team Sweeney is not just trying to become a platform but a next-gen entertainment ecosystem. One wonders when Epic will announce its own music and film production labels.

Finally, non-endemic firms have stepped up their investments in gaming. Historically consumer-facing organizations have kept their initiatives modest. Even a project like Burger King’s release of several hamburger-inspired titles on the Xbox to promote its chain of fast-food restaurants was clearly a one-off. But today things look rather different as the growing number of non-endemic firms pushing into gaming is diverse and well-funded.

One sub-group in this category consists of adjacent entertainment companies. Over the past two years, we’ve heard an increasing amount of clamor coming from Netflix which has been hiring senior execs from the games industry to head its own internal division aimed at growing and retaining its subscriber base. Similarly, a film production company like A24 is showing increasing signs that it is exploring video games as a key growth area. And not to be outdone, Warner Music Group recently announced a collaboration with Peleton around a guitar-hero style cycling game and a partnership with blockchain gaming company Splinterlands. Oh, and this week we learned that Snoop Dogg has joined FaZe clan as one of its board directors as the “esports media platform” readies itself for a public offering.

A second subset is consumer packaged goods. Among the growing number of brands looking to reconnect with younger audiences via games, high-end clothing labels offer perhaps the most credibility. Cross-collaborations of fashion design showing up in-game and iconic game-couture mincing down a real-life runway present an obvious marriage between design-heavy industries.

The eager builders of emerging technologies form the third sub-category. They range from a startup-gone-wild like Sky Mavis that benefitted from the surge of attention for cryptocurrency and saw the popularity of its Axie Infinity skyrocket in just a few months to a big tech incumbent suffering an identity crisis like Meta. Despite their different business models, these would-be innovators all share the conviction that interactive entertainment will catalyze user adoption for their proprietary inventions.

These are but a few examples, obviously. But they illustrate that the momentum we see in the games market today is the result of three powerful and well-funded industry groups coalescing at the same time. Among other things, it explains why market concentration in the games industry has remained relatively low, despite an accelerating rate of larger acquisitions.

The next decade in gaming

But it does bring some worrying long-term implications, especially around innovation. With an exacerbated sense of risk aversion, publishers have started to offset their dependence on only one or two franchises by expanding their IP catalogs. Embracer, for instance, has been on an absolute studio buying rampage. Take-Two regularly boasts it has 93 titles under development. Others are riding the brake. Activision Blizzard hasn’t made any meaningful acquisitions since King Digital nor released any credible expansions or replacements of past successes. And EA, well, it’s still thinking about things.

As platforms expand their first-party content and cross-platform capabilities, they are better insulated from market volatility. But it blurs the lines between their roles as platform holders and game publishers in the industry. In the short term, we’re told, existing titles will get equal access and marketing support. But what does that look like in five years? And, how much innovation can we really expect here? Platform holders are not known for their innovation.

With less to lose currently, non-endemics may yet offer up something we haven’t seen before. That depends, of course, on whether or not the commonly iron-fisted brand managers and solipsistic tech firms will allow for it. Their loyalty is with the mothership and content, whether interactive or otherwise, must serve the primary revenue model.

Abundant growth in combination with big firms’ risk aversion spells the onset of mediocrity. There’s a good chance that the dominant logic that governs conglomerates will come to serve as the playbook for strategy in gaming as well. Once the current momentum ebbs away, many of them will be tempted to manage for margins.

Let’s hope not.

NEWS

Valve releases Steam Deck to mixed results

Looking increasingly like a white wizard, Gandalf Newell made the rounds the past few weeks to promote Valve’s latest hardware innovation, the Steam Deck. The man is a legend and rarely comes down from his mountain. And when he does, the industry listens.

This time, Lord Gaben spoke much about PC gaming’s long-term viability as an open platform and why he eighty-sixed NFTs from his digital storefront (fraud). Unlike other, non-wizard executives, he brings a message that is as broad as the Steam Deck is wide. His industry peers to the degree that he has any, usually show up in a leather jacket and a three-sentence script to drive home a singular point: buy our new gizmo. Not Newell. He’s been making the rounds speaking on all the things.

What stands out to me is how much time he spends discussing hardware innovations. Valve built its success on a combination of great content and its digital distribution platform. It seems odd, then, to insist on pushing out physical machinery. It echoes the strategies we’ve seen at other digital-native firms. Riot Games decided to establish its own internet backbone at the height of League of Legends’ success, for instance. Building hardware that significantly improves latency issues proved an effective method to retain players and attract new ones. It’s an incredibly difficult and expensive act to follow for any would-be rivals.

Perhaps that’s how Valve’s thinking about it, too. With a proprietary, albeit an open, piece of hardware, it effectively insulates itself from up-and-coming competitors like Epic. Building a digital storefront was a notable innovation twenty years ago but now requires a physical moat.

Even so, the initial response among reviewers has been lukewarm. The Verge says the device isn’t ready yet. But that may also be because we’ve been holed up at home for two years and many of us have forgotten how to travel. But, again, not Newell. He’s been hand-delivering units in the Seattle area.

North Korea’s strained relationship with video games

If I’m honest, I had mostly abandoned the idea that North Korea would somehow have video games. It is a central tenet to much of my writing that everyone plays, regardless of cultural context. But after inevitably falling down the rabbit hole of Mass Games—the kind where thousands of North Koreans perform a synchronized routine en masse in honor of their leader—I hadn’t really looked back. According to a recently released journal article, “games now constitute the bulk of the software on sale in the country's IT retail stores.” Call me gobsmacked.

Titled “Reverse Engineering North Korea's Gaming Economy” it explains that North Koreans do play video games and, more so, that relationship is paradoxical, to say the least. On the one hand, many of the available titles are pirated from western economies and released after “removing foreign cultural elements, injecting domestic propaganda, and claiming full ownership of the modified software.” It serves to counter the notion of consumerist culture.

On the other hand, these games do employ microtransactions. Through a cumbersome system of QR codes that has to be taken to a physical store to complete payment, players can purchase in-game currency. Ironically, North Korean games foster “consumerist and profit-seeking behaviors that are at odds with the country's professed orthodoxy.” Fascinating.

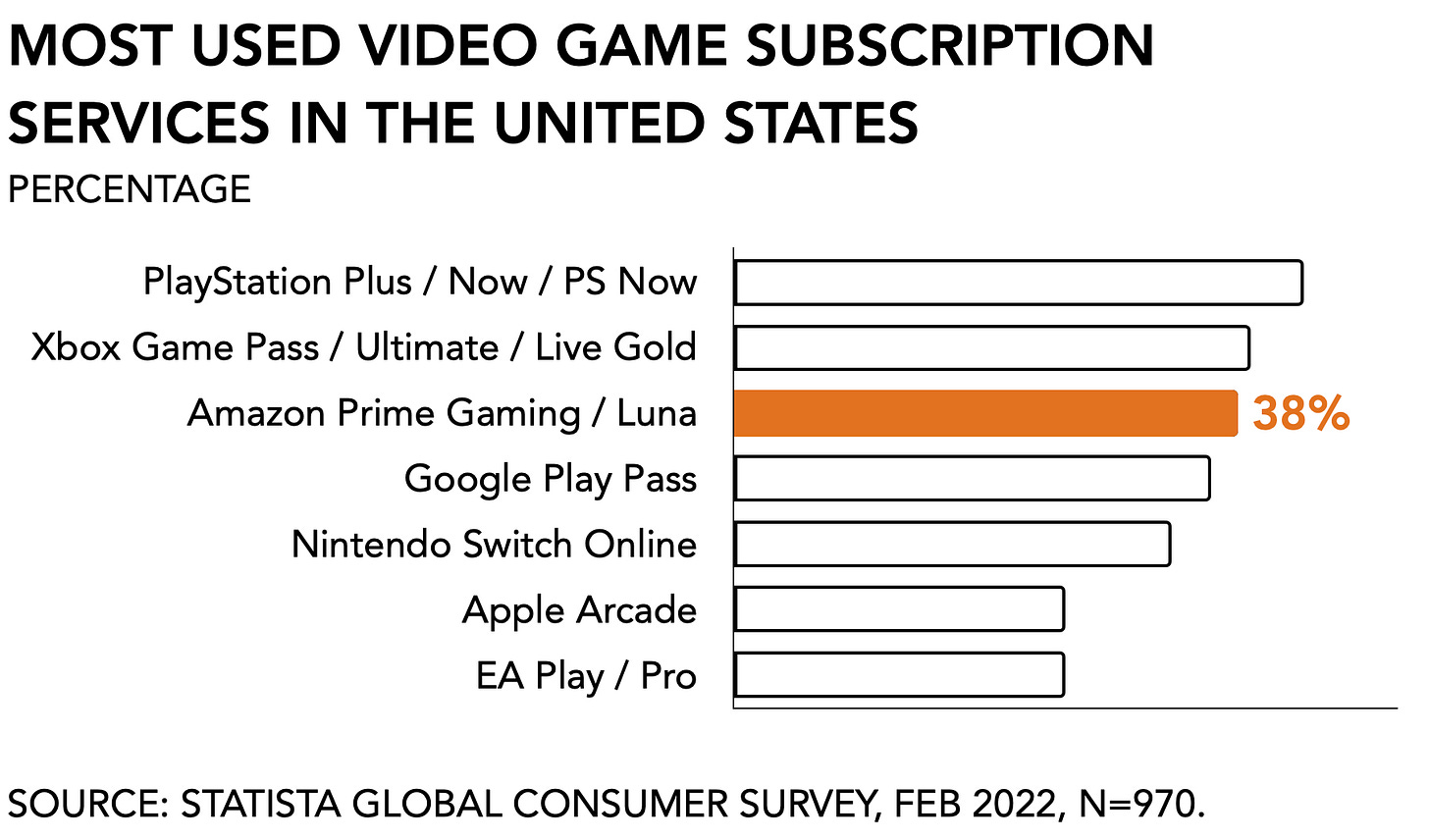

Amazon’s Luna service goes live in the US

Despite a far more modest kick-off than Stadia, Amazon made its cloud gaming service available last week. Bolstered by the recent success of Lost Ark, Amazon is on its grind and clearly intent on making this gaming thing work. Given that it rammed into some real opposition early on and stuck with it anyway, the perseverance is beginning to look convincing.

Gaming obviously continues to be an odd one out in the e-commerce empire. Projects like Crucible proved a bar too high on delivery. And just last week sister-division Twitch proved to be suffering from an executive-level exodus. Getting a win now is key.

So far Luna seems to be making a strong case. Sure enough, it all feels a bit cluttered to look for your games access amid the shoes and knock-off consumer electronics in the abundant online storefront. But once there, navigation proves smoother. One thing that works rather well is the Twitch integration and the way it allows me to quickly dip into a stream to see whether or not I want to bother booting up Devil May Cry 5 or Immortals Fenyx Rising.

Amazon shows a willingness to fail repeatedly in the hopes of eventually getting it right. That’s more than you can say for Stadia. But it also isn’t nearly on the same level as Microsoft’s xCloud offering or even Sony’s. That puts it in the running for third place which seems about right.

PLAY/PASS

Play. If nothing else, Nintendo is consistent in not giving a damn about sharing their digital data.

Pass. Ninja is offering a 30-day master class on how to become a streamer.

Play. Kids learning about goofy salamanders through Fortnite and Minecraft is the type of feel-good news we deserve right now.