Over the past few weeks, I’ve spoken to several industry colleagues and friends who are writing or thinking about writing, a book. And because last Friday it has been 500 days since my own book, One Up, came out, I figured I’d share some of the details on how that’s been going.

In the career of any knowledge worker—whether they are reporter, analyst, academic, essayist, or just filled with words—publishing a cohesive work of writing means having to confront at least two anxieties.

The first relates directly to your relative sense of job (in)security. In academia, especially in the humanities, there exists at least some degree of transparency when it comes to the requirements for tenure. Having a book out is key to securing long-term job security, for one, as it brings infinite glory to the department. In journalism, it similarly establishes job security, although it is not required. From what I’ve been told, writing a book as a reporter helps you carve out your own turf.

The second anxiety has to do with the quantification of your success. Books are discrete units. And just like we measure success in gaming by the number of units sold, in music by the number of albums sold, and in movies by the number of tickets sold, your sales figures seemingly serve to tell you your standing in the marketplace of ideas. It’s the calorie counting equivalent of your intellect.

Most writers manage to ignore both counter-productive ideas. The effort serves as a personal endeavor to summarize and extract some of the wisdom from all of the things you’ve seen and heard over the past years and share that with others.

Sales

To date, I’ve sold a combined 3,445 copies. That is more than I had expected. A lot more, in fact. Most of my academic peers told me that they sold a few hundred copies, including those whose area of expertise proved relevant or timely.

Of the total, 2,487 were hardcover sales and 958 were e-books. Roughly one-third of readers apparently preferred a digital copy. From what I can tell it is especially students and people in finance and tech that prefer the digital version.

The bulk of sales took place in the last quarter of 2020. Fresh from the printer, more than a few people gifted copies around the holidays. The absolute highlight was a student’s request to sign a copy for her brother’s birthday because he “was really into games.” Come to think of it, if that had been the only copy I had sold, I would have considered the entire effort a success.

Sales in Europe were a bit slower at first, and people reached out asking where to buy it. That proved to be temporary as copies made their way over there. And, finally, I’m told that a Russian translation is in the works. Imagine that.

Marketing

The biggest contributor outside of the marketing effort by the publisher and myself were, you guessed it, podcasts. First, in November 2020, I explained to an incredulous Scott Galloway that Roblox was going to be a big deal. That was fun. Next, it got picked up by an investment podcast, Invest Like the Best, in January 2021. My conversation with Patrick O'Shaughnessy on the underlying business model for GameStop proved popular and fortuitously timed, even if that thumbnail impression of me haunts me still.

Next, it’s been immensely rewarding to see people regularly post images of the book on Twitter and other social media. The support has been really heart-warming. And it forces my jealous ego to admit that I am indeed capable of producing something that people appreciate.

Revenue

As for the monies, I’d recommend tempering your expectations to get rich. Certainly, you get a percentage of sales (which my publisher asked me not to share). But there are also plenty of expenses involved. In my case, much of the data work was handled by research assistants who, at the time, worked at the firm I ran. That type of access to resources is rare, I realize, and an important reason why it was rewarding to get to write at all.

In the parallel universe of the music industry, the economics are comparable. Where in the past musical artists used to do live performances to promote an album, today the revenue model is inverted. Streaming music serves as a promotional tool for your oeuvre, and musicians monetize by doing live shows. It’s a bit like being a pilot: you only get paid while you’re flying the plane.

To that end, I also considered self-publishing, of course. Even if the academic literature speaks in favor of working with a platform or publisher to reach the broadest possible audience, the idea of retaining 100% control was appealing for a while. But then it proved to be just a bunch of extra work in addition to writing and my day job. No thank you. Finally, because I relied heavily on data tables and charts, getting all of it neatly into the proper format proved a bridge too far.

As for things I would do differently next time, I am going to spend less time doubting my work. Since the start of the project in 2017, I’ve slowly developed a writing process that works best for me. It remains an intimate process of slow composition. But you really can’t trust your anxieties around it. To eradicate it further, I’m putting together the outline for the next book. My publisher is asking what’s up. And a buddy tells me that publishing one book makes you a writer. But publishing two makes you an author. Something to strive for!

All kidding aside, to all my friends out there writing their own, let me know if it’s helpful. Let’s talk. And then get back to work!

On to this week’s update.

BIG READ: Uncharted, the movie, breaks no new ground for games biz

A few times a year, the release of a film based on a video game franchise offers a moment to check in on how the two industries relate.

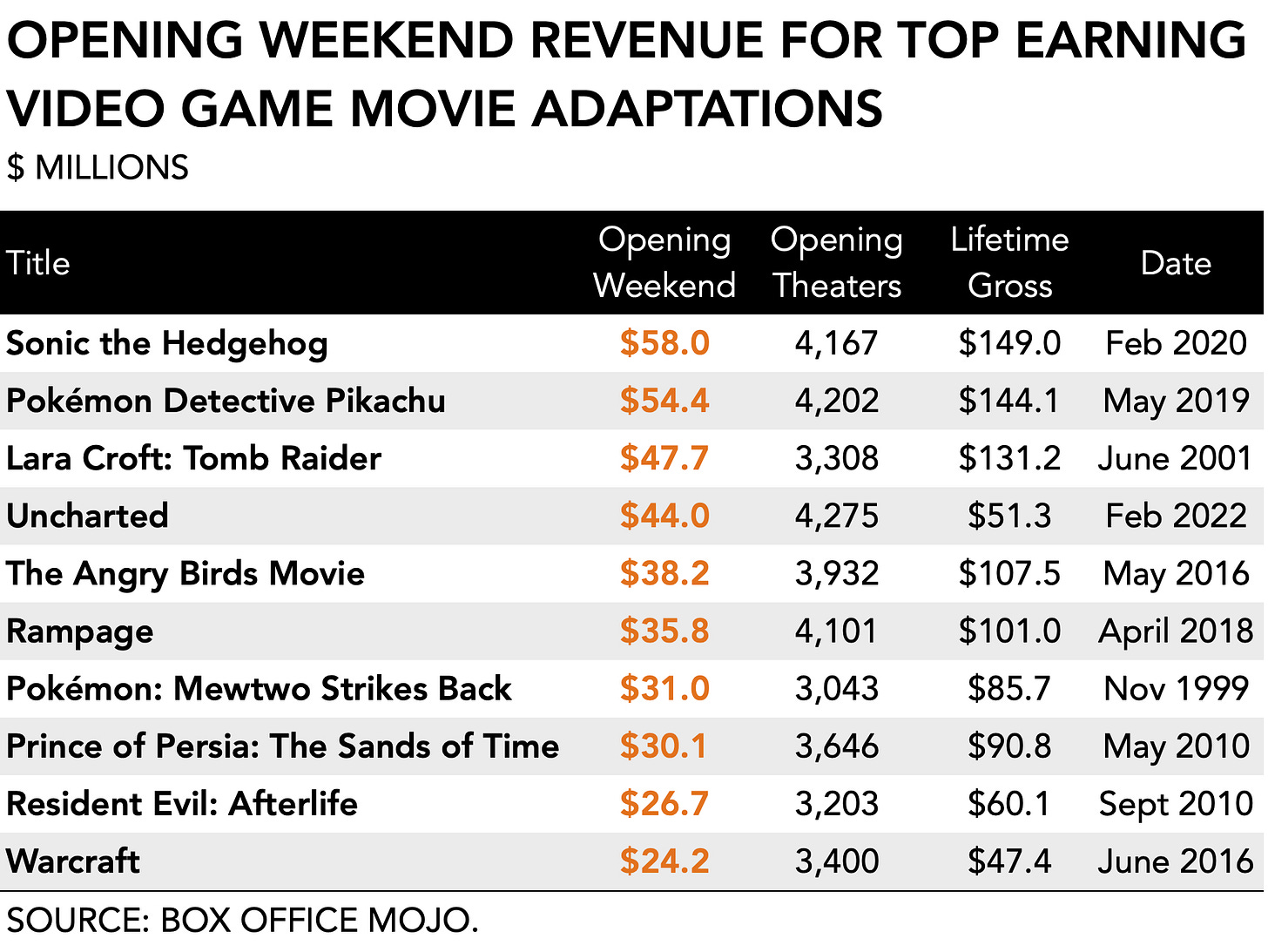

Historically, their dynamic hasn’t been great. Video game adaptations were a sure way to lose a lot of money. Often no more than a sideshow, brand managers would sell off the movie rights to producers that barely played games or understood the lore for even the biggest franchises. According to most filmmakers, video games were simply a lower rung on the cultural ladder and undeserving of any real artistic attention. And, fatally, adaptations proved a terrible financial venture. In the decade between 2000 and 2010, the average production budget for a video game adaptation was $52 million. But the average profitability of $40 million meant that on average films in this category lost -23 percent. Exceptions characterize this period. Tomb Raider (2001) remains one of the top-grossing films but pretty much all other game-related movies from that time sucked.

Since then things have changed. The rapid popularization of interactive entertainment resulted in an increase in demand. Audiences don’t just want to play a game, they want to inhabit it. Financial outcomes shifted accordingly. Since 2010, production budgets increased +46% to an average of $77 million and profitability jumped to +95%, for an average of $150 million per film.

Certainly, there exists an enormous spread between different productions and their box office successes. But given that the average number of opening theaters for films in this category has increased from sub-2,000 in the late 1990s to well over 3,000 today tells you that Hollywood is leaning into gaming.

More so, video streaming services have discovered fertile ground in gaming. Netflix has been spending a lot of time and attention on producing binge-worthy series based on The Witcher, Castlevania, League of Legends, and others. Sure enough, Hollywood considers video game IP now good enough to serve its financial needs. But isn’t the games industry selling itself short?

I think it is. In fact, I’ve argued previously that the games industry continues to be wildly insecure about its own cultural significance. Releasing a film or TV series somehow seems to mean it is relevant. It doesn’t. But so many of the current decision-makers in the games business are deeply convinced that gaming is merely a creative stepping stone into more established entertainment industries.

The legendary Kojima has made no secret of his ambition to one day make movies and promptly filled his first independent production with a cadre of celebrities. Embattled Bobby Kotick started Activision Blizzard’s esports division as his ticket into the next financial echelon: are you really a billionaire if you don’t own a sports team? And Strauss Zelnick, perhaps the most promising media mogul the games industry has to offer, populates Take-Two parties with beautiful people from the music business. His recent acquisition of Zynga reveals an appetite that goes well beyond even the success of GTA. And suddenly the firm has teamed up with a slew of new partners, including LEGO and Netflix.

In fairness, the game Uncharted borrowed generously from Hollywood. Its main character, the narrative arc, the Indiana Jones-style adventuring, and the treasure hunting are all obvious movie tropes. In fact, the whole franchise is an interactive, albeit railed, movie. Similarly, something like The Last of Us 2 is deeply rooted in the apocalypse survival genre that proved so popular on TV even if you’d be hard-pressed to find an equivalent gut-wrenching experience on your idiot box. More broadly, much of the North American games industry has traditionally borrowed from Hollywood’s playbook. The underlying economics, development, financing, and marketing resemble those of large blockbuster productions.

But for me, it falls apart in those moments where the games industry offers up the best of itself for something of lesser value. A single silver screen production offers a highly reduced extract from an interactive experience that can take up to 80 hours to complete. Rather than paying homage and making a humble contribution, film and TV makers are more interested in cherry-picking key narrative elements. In the announcement for the Halo TV series, the focus immediately went to revealing Master Chief’s face. After twenty years of mystery and mythology, the literal first televised show wanted a scoop and set the tone. And Master Chief’s voice will be new to all of us, too.

Finally, beyond the imbalance of the current relationship, novel forms of entertainment will emerge from the exchange between video games and film. The current obsession with the metaverse is mostly going to manifest itself from their dialectic. Already did we suffer through Ready Player One and its wild ideas about what gamers are like. So, too, did Black Mirror present us with an image of players that can only be described as sociopathic. And even a kids movie based on an arcade game like Wreck-it Ralph 2 pulled no punches presenting us with the usual boomer-cynicism on what online life looks like.

Meanwhile, the Avengers and Master Chief come together in Fortnite to do a jig and enjoy themselves. The literal playfulness of online environments allows for a broader range of creative expression and expertise. It suggests that franchises that originate in gaming will become more popular in the years to come because they don’t require the type of strict control that characterizes Hollywood. The same iron-fisted solipsism that has served movie makers so well may prove less useful in a metaverse filled with messy interpretations of new and old franchises.

The games industry shouldn’t sell itself short now that filmmakers take a liking to its IP at the dawn of a new era in entertainment in which interactivity leads and passive consumption follows.

MONEY, MONEY, NUMBERS

Ubisoft reported $843 million in revenue. Down -25% compared to the same period last year, earnings fell within guidance, but still managed to disappoint some analysts who were hoping for a $901 million consensus. Digital revenue dropped -10% y/y to $600 million, which accounts for 71% of the total. Back-catalog sales increased +10%, as Assassin’s Creed Valhalla and Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six: Siege continued to find traction. Its more recent release, Far Cry 6, however, “did not reach the high end of its expectations.”

Embracer generated $545 million in revenue, up +135% y/y. After its buying spree, overall earnings are obviously up, and it reported +175% of y/y growth for its gaming division which earned $399 million. By comparison, its partner publishing and film division generated $146 million and was up +67% y/y. According to management, especially Koch Media and Coffee Stain were strong contributors to its growth in gaming. Embracer’s mobile games business reported 292 million monthly active users, and 34 million daily actives. Embracer has 216 game projects under development and plans to release 25 AAA projects by March 2026. Its headcount is now 9,524.

Stillfront’s 21Q4 revenues reached $156 million, up +34% y/y. The firm fell short of a consensus of $201 million. It reported a total monthly active user base of 64 million in Q4, up +195% y/y as a result of its various acquisitions. Of note is the firm’s reliance on advertising revenue which accounted for 19 percent of total bookings, up from 8% in the same period last year. Stillfront also provided a breakdown by product area: Casual and Mash-Up accounts for 47% of revenue, followed by Simulation, Action, and RPG (29%), and Strategy (24%). It is not immediately clear to me why they slice things that way.

Nacon acquires Daedalic Entertainment for $60 million. Just weeks after its acquisition of Edge of Eternity, Nacon hits us with another acquisition. The transaction is split between $36.3 million in cash and another $24 million if milestones are met. Daedalic’s main project today is the development of The Lord of the Rings: Gollum which is bound to benefit from Amazon’s push behind the upcoming series for its Prime service.

Krafton acquires 5minlab for $20 million. Founded in 2013, 5minlab is a mobile game studio in South Korea. It is unclear to me how well that is going because the entire deal is an earnout payout. So much for valuing a studio’s ability to take “bold challenges.” Nevertheless, Krafton is clearly looking to expand its mobile business.

PLAY/PASS

Pass. A self-proclaimed “first protest in the metaverse ever” against the colonization of decentralized virtual space by capitalists reads like a poorly-phrased press release that talks more about the artist than the cause. Everyone is selling something to someone.

Pass. The new Street Fighter logo is uninspired. So is the fallout that followed. Yawns all around.