Last weekend a friend and I recounted van Persie’s equalizing header against Spain in the 2014 match of the World Cup. It is perhaps one of the most brilliant goals scored in the history of the game. Yes, I know that’s a strong statement. Here’s why.

Four years earlier the Spanish had defeated the Dutch in the final of the 2010 World Cup. The Spaniards were the reigning champion and absolute favorite. Brimming with self-confidence and an early lead due to a penalty kick, they started playing lackadaisically and taking liberties they could not afford. Just prior to van Persie’s goal, Spanish striker Silva missed a golden opportunity by underestimating the goalkeeper.

The Dutch, meanwhile, had a lot to make up. You have to understand that the Netherlands prides itself as a “small country that achieves big things.” The unsatisfying loss in 2010 of 0-1 still burned in the collective mind of many. In the years that followed, the national team had been rebuilt and all eyes were on a new generation of Dutch players. However, the early Spanish goal suggested that it would be much of the same.

Van Persie’s header at the end of the first half came as a release from a four-year fever. A fantastically accurate pass landed out of reach for the Spanish defenders and gave van Persie the room he needed. The goalkeeper seemed frozen as the ball flew right past him into the net. It singlehandedly turned the match around and undid years of soccer-induced anguish for the Dutch.

Now, I doubt that many reading this newsletter care much for the nationalistic vanities of a small European country channeled through soccer. But here’s the principle:

Games tell us about ourselves

The rules of a game reflect the principles and set of beliefs relevant to its broader cultural context. Since many of my readers are from the US, perhaps the following makes more sense. Baseball has long been regarded as the sport that represented rural America. It has no clocks, teams take turns at-bat, and if the game is tied after nine innings, another one is added. The objective for each player is to score points for their team by overcoming a challenge on their own and getting ‘home.’

Football, on the other hand, is regarded as a pastime for urban, industrialized America where people closely adhere to a time schedule. Points are scored by penetrating the opposing team’s territory and this is achieved by players seamlessly working together along meticulously defined strategies.

The list of differences is much longer, obviously. But suffice to say that how we play carries important clues as to the broader set of beliefs that we hold. In the context of video games, seeing the emerging preferences of a new generation of players manifest tells us what they are about. Against a background of a changing industry that has largely moved away from its product-based roots to become a service-based entertainment category, popular titles today have at least three traits in common that set the tone.

I choose you

For a long time, playing a video game was largely a performative activity. Early arcades asked you to jump barrels and time your movements. Playing Donkey Kong was the same for everyone, from its avatar to its challenges. The popularisation of collectible card games changed that.

At NYU I have the privilege of teaching a wide variety of students from all over the world. It benefits my classroom enormously to hear from others what gaming is like in other countries. To get everyone on the same page at the start of each new semester, I ask my students if they played Pokémon. On average 90% of them have. Despite their diverse backgrounds, they have a shared frame of reference.

The broad appeal of a collectible card game like Pokémon is found in its slogan: ”I choose you, Pikachu!” It is a seemingly universal truth that 10-year-olds around the world have very little agency in life. They’re largely told what clothes to wear, what food to eat, when to be ready for school, and what chores to do. How wonderful then to decide on your own Pokémon deck, choose your favorite characters, and develop your own strategies for playing with your friends. In this context, agency becomes a form of expression.

We see a similar element of decision-making and player empowerment across other popular tiles. Minecraft, which currently has an excellent exhibit in New Jersey, allows people to build an enormous variety of things and create their own private worlds. Fortnite offers a broad range of cool characters and items to explore that draw from cultural references elsewhere. The presentation of self in a digital environment, or as a digital environment, is increasingly central to play.

Bowling alone no more

The multiplayer component is a second aspect of contemporary games that stands out. I spent most of my summer in 2016 helping financial firms and journalists accept that, indeed, everyone is a gamer. That year the overwhelming presence of millions of people playing Pokémon GO everywhere across the world evidenced that gamers were not just a narrowly defined demographic, but, well, everyone and anyone. Washington Square Park near NYU was teeming with people playing together, hanging out, and enjoying themselves catching Pokémons. Beyond the size of the audience, it also showed that this generation liked to play together.

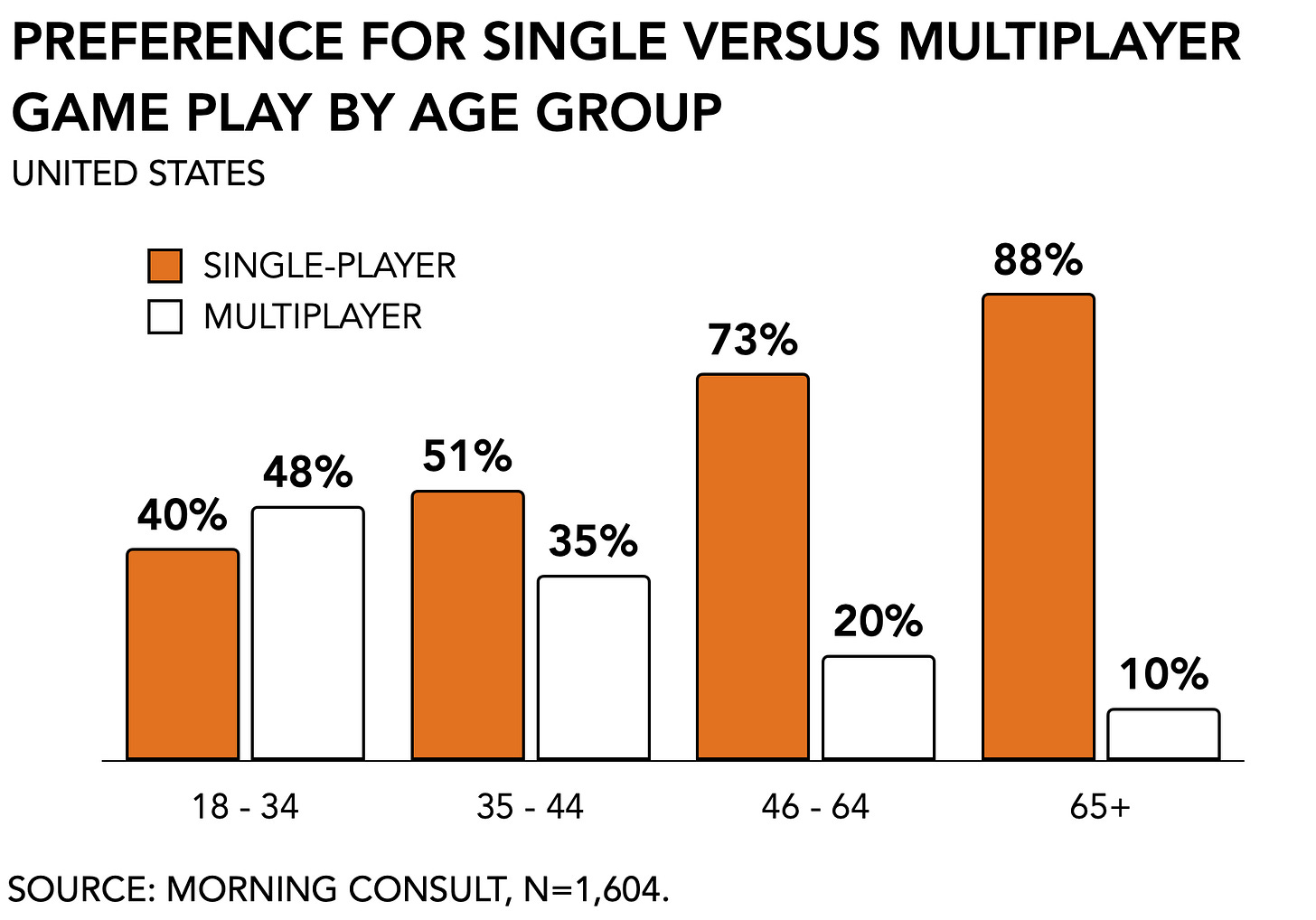

Online experiences are similar. Roblox presents a social white space where people choose who they want to be, what they want to wear, what they want to do, and with whom. According to Deloitte, among younger generations like Gen Z and Millenials up to 96% count video games as one of their top three most frequent activities compared to 89% for Gen X and 57% for Baby Boomers. Notably, playing with others is most popular today among younger audiences, who show a preference for multiplayer gameplay. Conversely, among gamers aged 45 and older, roughly three out of four prefer playing single-player games.

Two decades after Putnam wrote his book, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, in which he details the erosion of “in-person social intercourse” a new generation has found a way to reconnect, while older players prefer to play alone.

A third element of contemporary play is the increasing prevalence of co-creation. Altering and adding elements to an existing one has been part of game development from the start. The popularity of Doom by id Software was in no small part due to the vision of its creators to release a shareware version that allowed amateur coders to create and share levels for the game. At a time when PC gaming had been relegated to the fringes in favor of the walled-garden approach that characterized the console business, this approach quickly established a thriving fanbase and cemented Doom as one of the most popular franchises.

Until recently few firms meaningfully facilitated the instinct of ardent players to add and share their personal interpretations of a game. During an investor call Andrew Wilson, Electronic Arts’ CEO, observed:

“There’s also another secular trend that’s happening inside our industry around user-generated content, open-world, and interaction... So as we think about our future [and] growth, a big part of it is choosing games that not only themselves have appeal, but can benefit from secular trends.”

That’s a remarkable thing to say for the publisher of Will Wright’s brainchildren Spore and The Sims. The former was predicated on the idea that players wanted a completely procedural environment in which to experiment with a wide range of possibilities as they carried a customized life-form through its various stages of evolutionary development. The latter lent itself so well to modding that its creators outproduced EA’s salaried designers 8x in terms of assets.

The drive to create and actively participate is increasingly manifest. Just last week, Epic Games’ CEO, Tim Sweeney, stated in an interview with Fast Company that soon the company will allow anyone to create content for Fortnite.

“Later this year, we’re going to release the Unreal Editor for Fortnite–the full capabilities that you’ve seen [in Unreal Engine] opened up so that anybody can build very high-quality game content and code . . . and deploy it into Fortnite without having to do a deal with us–it’s open to everybody.”

Confirmation of continuity

There are more, of course. There exists a world of difference between what it means to play games in your proverbial parents’ basement and to attend a live event with thousands of other people who enjoy the same things you do. But interactive entertainment is changing because its players have different wants, needs, preferences, and reactions to the world they grow up in.

It has amounted to video games becoming much more than an isolated, singular experience. Already during the pandemic did people begin spending time online together in ways we had not seen before. From birthday parties in Roblox to full Dungeons & Dragons sessions via Zoom, life kept ebbing and flowing through the medium of games when in-person social life had come to a halt. Now, games are quickly becoming the place where we affirm that the world is still turning and experience a confirmation of continuity through a connection to others.

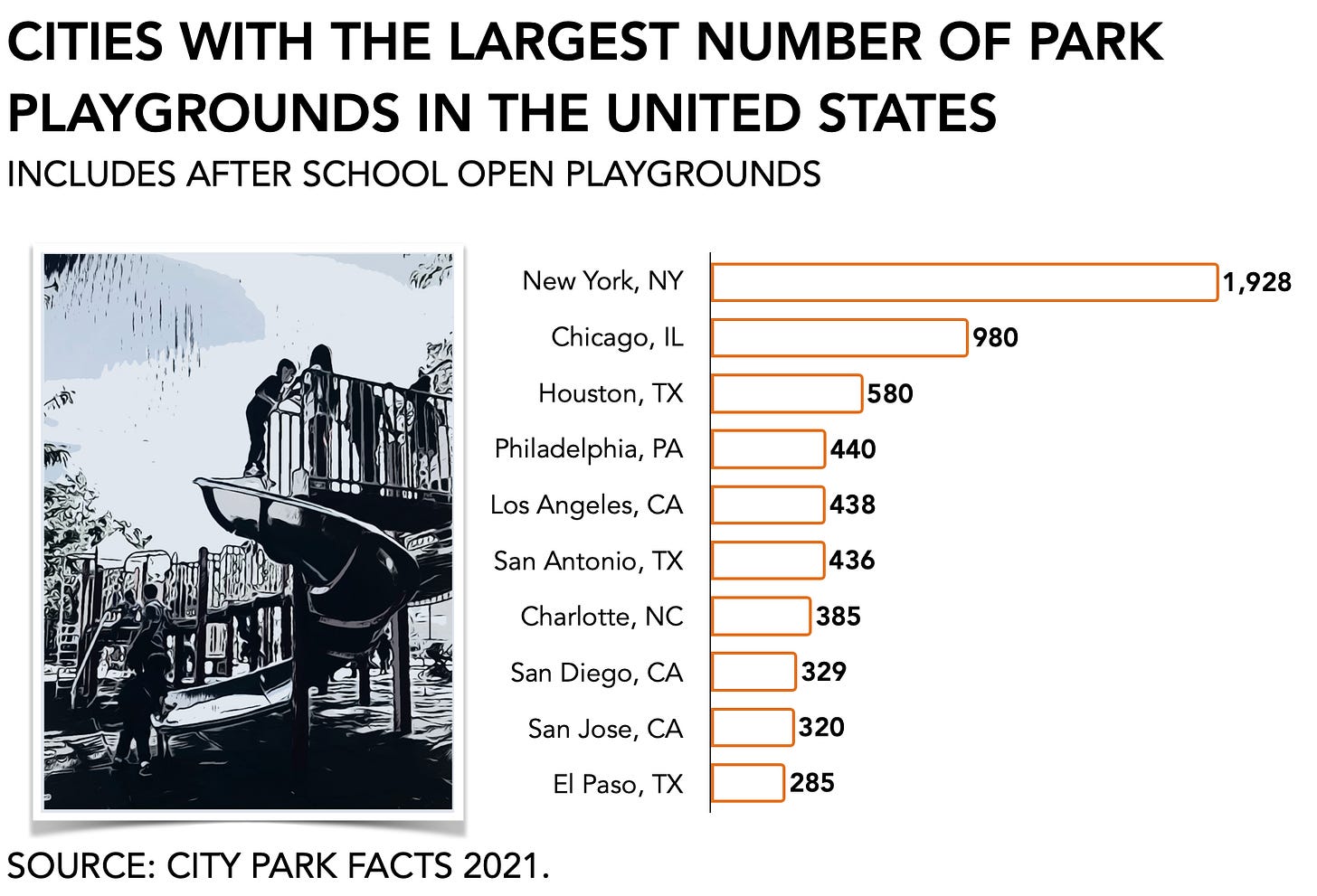

We could even go so far as to say that the next generation of video game audiences indulges in a novel form of escapism. Take playgrounds. Walking around Brooklyn it always amazes me how many playgrounds there are.

In New York, I learned, there are 1,928 playgrounds, or roughly 2.3 per 10,000 inhabitants. That puts it close to the US median of 2.8. In some cities, kids are clearly lucky to have any playground access at all. Los Angeles has 1.1, Phoenix 1.7, and Dallas 1.8.

But as deliberately designed play spaces, playgrounds encourage and discourage certain play activities. According to a recent article that analyzed the social, cultural, and political value of play,

“A play-space that directs the child—where play fixtures are one dimensional (allow only one play activity, usually related to muscular activities i.e. swings, slides, seesaws) or where play equipment is fixed and cannot be manipulated by the child—showcases designers’ inclination to control the child and channel his behaviors.”

Contemporary video games facilitate a much broader variety of activities than the ones that were popular a decade or two ago. More so, rather than trying to get away from the drudgery of daily life to engage with a synthetic universe that is consistent and where effort is rewarded, newer digital play experiences seek to counter-balance the increasing over-scheduling and micro-managing of children’s lives. Nowadays, play isn’t *just* the antidote to a boring job, but an exercise in chaos, thrill-seeking, and expression. The decline in unsupervised playtime that would allow children to develop the skill set necessary to navigate social conflict and learn, literally, how to play nice with the other kids, will ultimately be a detriment to society, according to one study.

“Car accidents are a major killer of children, yet parents seem very willing to take that risk, but far less willing to, for example, allow their children to eat Halloween candy from strangers even though there is not one verified incident of poisoned Halloween candy on record.”

Agency, expression, sharing, negotiating online relationships and making meaningful contributions to that experience are key aspects of the generation of play to come. Watching such a shift raises questions for game makers, investors, regulators, and parents alike. What does it mean for a consumer group and how do they see themselves when they can finally celebrate their favorite pastime publicly for the first time in decades? How does that impact their long-term trajectory as a consumer group and the relevance of a broader cultural practice? If your daughter’s favorite friend is someone from South Africa in a different time zone that she met through Roblox, do you let her set an alarm to wake up early and say hi?

As an immigrant, I’ve tried to get into American football on several different occasions but to no avail. It’s not that I don’t like the sport, but I lack the cultural frame of reference that makes me as irrational as watching soccer does. Not having grown up with it, accepting a new ruleset always felt like hearing someone else’s name but never my own.

After turning the tide against Spain, the Dutch team eventually won 5-1. For a moment, we were already champions of the world. Or so the game would have us we believe.

I like your sports analogy, though I’d say the demographics for American sports have shifted quite a bit. Now, this is completely anecdotal so I could be completely off the mark. But based on my own observations, football seems to be rural America’s preferred sport du jour, as it’s seen as tough, manly, and patriotic.

Meanwhile, urban/educated America has engaged less and less with the NFL* mostly due to concussions/brain injuries, among other scandals; if anything, soccer’s probably more popular in cities, though I have no data to back this up (but I do remember Sacramento had been vocally begging MLS for *years* to give them a team, and a new stadium’s being planned for Miami).

*(College football seems to be holding on better, but that introduces a whole new set of variables to consider)

https://youtu.be/xF4xTDMhDl0