The SuperJoost Playlist is a weekly take on gaming, tech, and entertainment by business professor and author, Joost van Dreunen.

My head has finally stopped spinning.

This week I learned that whenever artificial intelligence makes something up, it’s referred to as a ‘hallucination’. Specifically, it refers to a confident response by an AI “that cannot be grounded in any of its training data.” Generally, a large language model gets things right and occasionally pulls things out of its artificial arse.

Enter the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority.

After the CMA released its final decision to block the Activision deal, an avalanche of reports followed discussing everyone’s consternation and what it meant. Despite a charm offensive, a myriad of concessions, and the UK regulator’s recent and unusual restatement of its provisional findings, Microsoft seemed close to a win, only to have the UK’s antitrust referee move the goalpost.

In an impenetrable 418-page document the CMA justified its decision with an uncanny ability to see the future is remarkable. It states:

“Since Microsoft already appears to face limited competitive constraints from current and potential rivals, we are concerned that withholding Activision’s content from rival cloud gaming platforms is particularly likely to harm competition now and in the foreseeable future.” (p. 19)

It argues that cloud gaming will be transformative and essentially come to replace, especially, console gaming. If it were one of my students, it’d get a C minus.

ICYMI, I’ve written extensively on the topic over the past year, including a submission to both the British and American antitrust regulators arguing that the acquisition would, in fact, benefit competition and consumers.

Here’s the punchline. Historically the introduction of novel distribution channels, revenue models, and platforms has made the pie larger. Innovations in gaming don’t take from existing successes but build on them and expand the range of options available to consumers and creatives. The popularisation of mobile gaming a decade ago did not result in the anticipated death of the console. Instead of becoming obsolete, console gaming expanded from $24 billion to $68 billion today. Throughout history, such changes tend to have a positive rather than negative impact. As the market for interactive entertainment grows, a greater variety of channels reaches a more diverse player base.

I must have missed that in the final report.

The CMA also seems to have an astute read on Activision Blizzard (ABK) that is unlike anyone else’s. For one, the publisher does not offer any subscriptions to its catalog, nor does it provide cloud access to any of its titles. Team Kotick has shown no interest in the model: it has mentioned the word ‘cloud’ precisely zero times in its most recent earnings reports. Even so, the CMA expects ABK to put its imposed independence to use by rolling out its own costly streaming service and making Call of Duty available on non-Windows PCs. It claims that

“absent the Merger, Activision would seek to maximise the value that it can derive from these games, which would have involved considering making non-Windows PC versions of its games.” (p. 20)

Call of Duty on MacOS and Linux? Activision Blizzard, we hardly knew ya.

Ah yes, says the regulator, but absent the deal, publishers like ABK will be rolling out their own service and cloud channels.

No, they won’t.

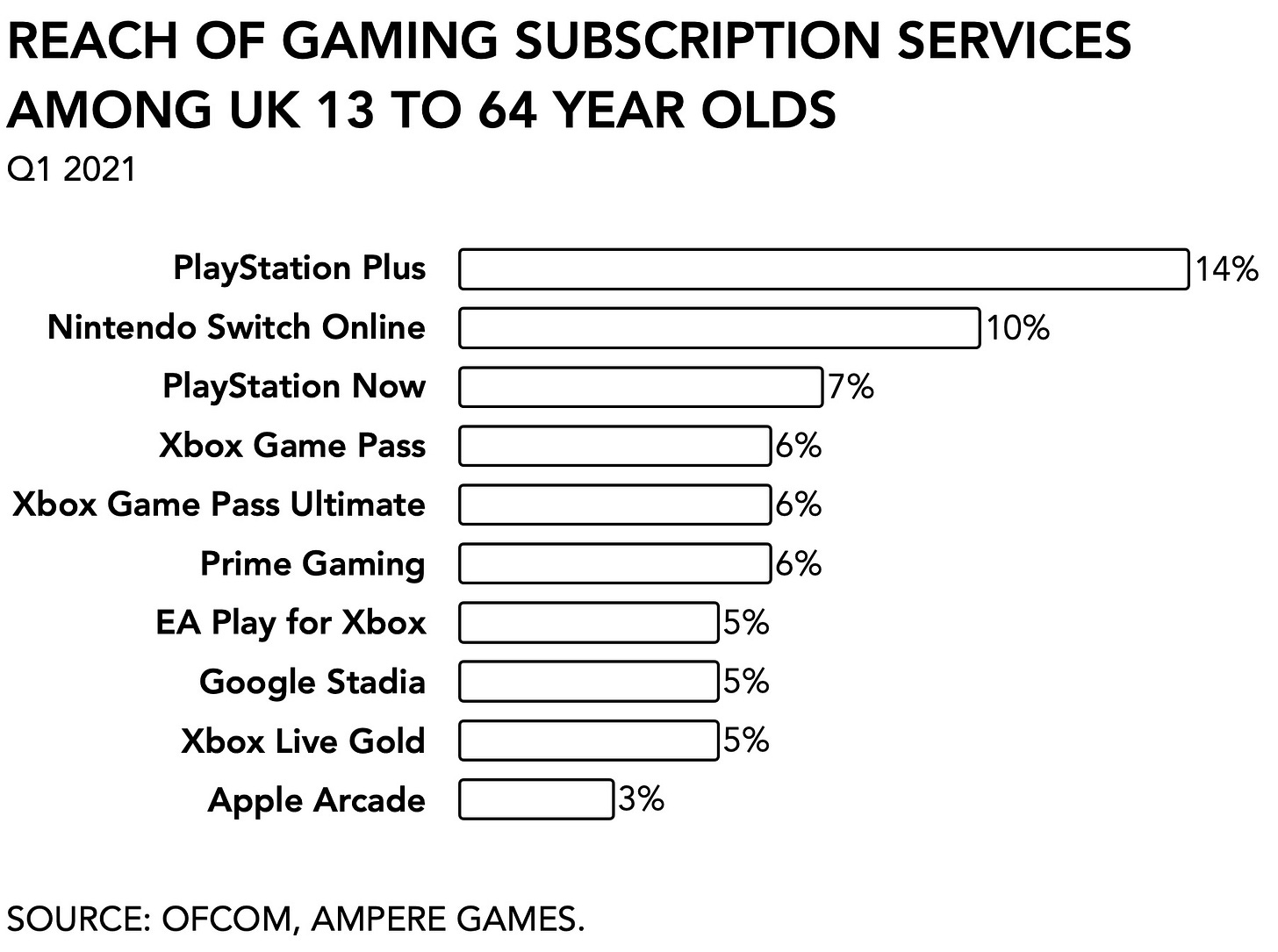

Here’s the top 10 list of gaming subscriptions in the UK according to Ofcom, a government-approved regulatory and competition authority in the UK. It publishes an annual study called Online Nation, which tracks how people spend their time online and includes a helpful overview of the top gaming subscription services.

Two things. Notice that it only has one pure-play publisher in it? That is because it’s hard to make more money by charging per title. Offering an entire catalog at a fixed price works only at scale, especially when balanced against infrastructural expenditure. And you’ll also observe that Sony is dominant here, too.

With the regulator’s decision, UK Consumers will have less access and continue to pay more for premium content like Call of Duty.

Anyway, I could burn down more of the CMA’s forest of deadwood arguments, but the focus is its expectation that the UK market will benefit from the artificially enforced competition.

It won’t.

By blocking the deal, the CMA has done a disservice to market competition. For one, it reinforces the existing market structures. In mobile, Apple and Google would have had to contend with a much more formidable competitor. While even the largest mobile game publishers have had to kowtow to Apple and Google, Microsoft operates as its own independent empire.

No, says the watchdog,

“as for Microsoft’s plans to enter the mobile gaming market, we found that these plans were far from certain, especially in current circumstances where the largest mobile OS—Google’s Android and Apple’s iOS—either currently prohibit rival mobile gaming app stores or impose strict limits on their ability to monetise content.

Having a major tech firm like Microsoft take a sizeable position in this otherwise heavily controlled market with two oligopolists would shift the balance somewhat. But the CMA disagrees. I guess we are just going to ignore the fact that just this week Apple successfully defended its case against Epic Games. A “resounding victory” for whom, exactly?

In the console category, Sony is the big winner. The Japanese game maker successfully convinced the watchdog that it is, in fact, the David of gaming, and not Goliath. Or, as Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella put it:

“We should probably look at Microsoft’s share of the console market in Japan and wonder why that is. Maybe they should actually start competing more. I hope that regulators take an approach that is truly beneficial to gamers and publishers.”

Sony doesn’t care about CoD, it says. According to Activision Blizzard EVP Corporate Affairs and CCO Lulu Cheng Meservey, Sony’s Jim Ryan stated: "I don’t want a new Call of Duty deal. I just want to block your merger." Well, he got want he wanted.

What Ryan probably does not want is having to pay more for the franchise when it expires in 2024. Currently valued at $400 million a year in income, Sony has done itself a massive disservice by raising such a stink. After arguing that Microsoft’s 10-year license offering was “inadequate on many levels”, even though every other platform out there seemed perfectly happy, Sony can expect to pay substantially more when it is time to renew with ABK. Its campaign to block the deal may yet prove a Pyrrhic victory more costly than, say, investing in a cloud strategy. But the regulator’s decision does nothing to motivate Sony to establish its own infrastructure.

Chances are that any additional content acquisition costs will be transferred straight to UK consumers. By siding with Sony and insisting on maintaining the walled garden market structure, the CMA virtually guarantees that prices will go up.

Next, it is unclear how blocking the deal will benefit the well-being of people making games. The path to recognizing collective bargaining rights, or even just providing non-toxic work environments just got longer. Despite one of the largest unions in the United States, the Communications Workers of America Union (CWA), siding with Microsoft on the deal because the tech firm, unlike so many of its peers, proved willing to announce a labor neutrality agreement, ABK’s 9,500 worldwide employees will have to wait a bit longer.

Moreover, the industry at large has grown and will continue to do so. Consolidation is perpetually imminent. As one of the relevant markets in Europe, the UK is probably unconcerned with where the money for all those video game acquisitions is coming from. When it comes to soccer, however, both UK fans and the government turned on the Russian oligarchs that own its most prominent clubs long before the Ukraine war broke out. The recent flurry of purchases financed by the Saudi Arabian Public Investment Fund may prove to be similarly tainted.

If that’s too speculative, then consider the UK’s weakened competitive position in the global market. Nearby nations are increasing their investment in interactive entertainment at the same time that the UK is creating an adverse business climate. Why risk setting up shop there? Ireland won’t mind. But it won’t benefit either UK consumers or creatives.

Changing the win condition

All of this seems mild compared to the observations that, perhaps, these regulators are incapable of doing their jobs. Are they reasonable people? Probably. But I can’t escape the feeling, however, that ever since gaming became a more prominent culture industry, governments everywhere have been writing new policies without a convincing sense of understanding the market. What makes policy makers uniquely able to cast judgment and accurately anticipate how nascent markets will evolve? Especially the CMA’s narrow interpretation of cloud gaming as a singular distinctive market (which it isn’t), and stating that it “is vital that we protect competition in this emerging and exciting market” feels paternalistic.

I will absolutely concede that markets need oversight. And I agree that Microsoft’s ownership of ABK has the potential to become a disadvantage, albeit only if it reneges on its commitments and acts against its own interests. Cloud gaming, much like the current business models in music and video, requires a large and diverse audience to justify the costs of building infrastructure. Low latency is crucial for consumer adoption. To achieve this, Microsoft must make its service widely available and affordable. Dominating the market in an unfavorable way by raising prices or limiting access to parts of their catalog, would ultimately hurt margins.

Regulating regulators

At best, we’re witnessing a watchdog that is likely underfunded and short-staffed. It implied as much by releasing only 8 pages of summarized public comments after receiving 2,100 entries. In spite of thousands of people arguing otherwise, the CMA claims it knows better. But when it comes to showing their work, I struggle to find it.

At worst, we’re witnessing a regulator accidentally filibustering an acquisition. It has published reams of research that are mostly opaque and still largely inaccessible to the public because of its many omissions. If accountability and structural remedies are so important, an antitrust watchdog should make it a point to lead by example. Anyone arguing for ‘Do as I say, not as I do’ can go [✄] themselves. Those are yesteryear’s politics.

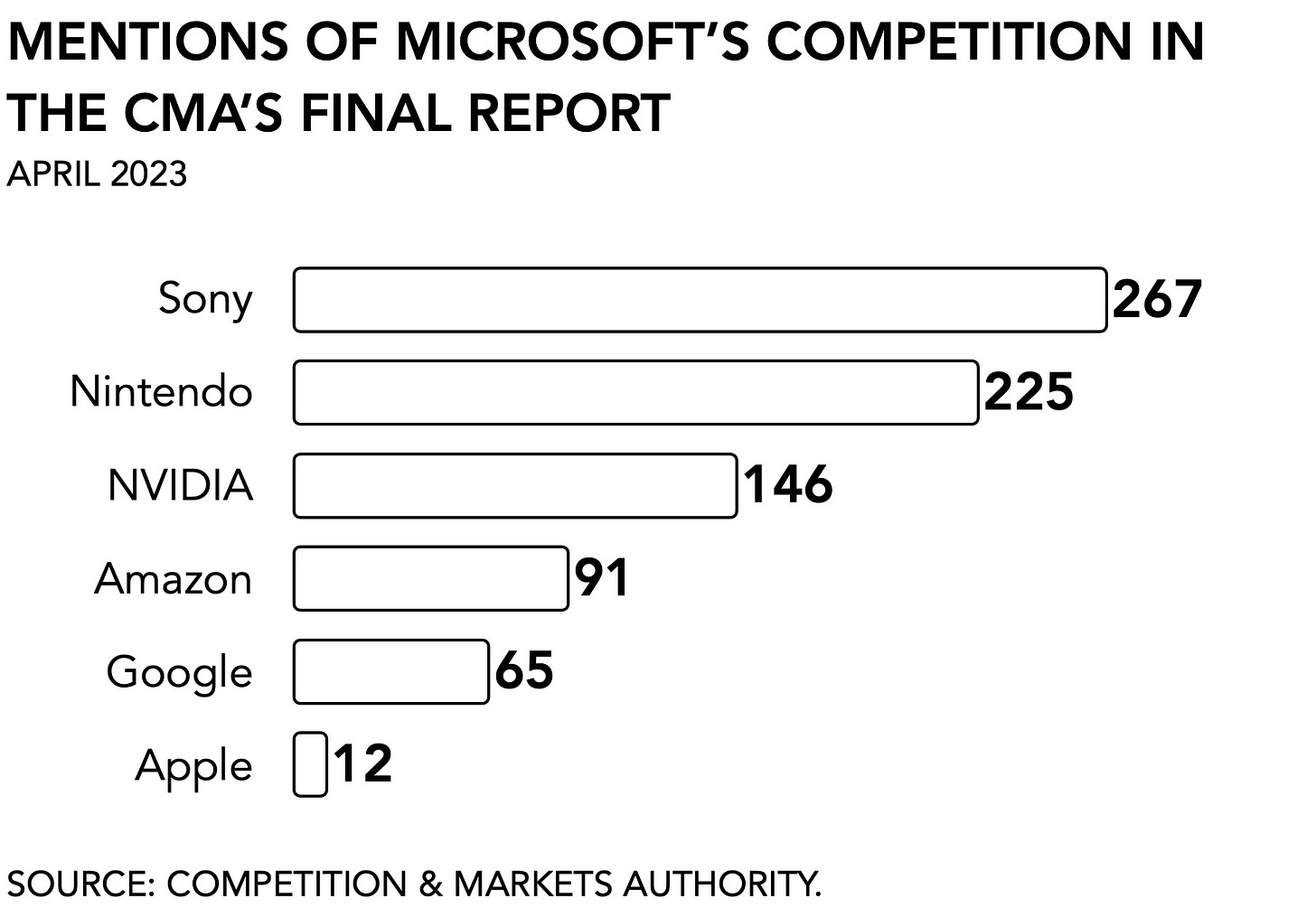

We can still count, however. And that, too, provides some notable patterns. For instance, providing such prominence to a direct rival in the conversation without acknowledging the relative market share between them seems fishy. But Sony is nevertheless heavily featured throughout the CMA’s final report and appears 267 times.

That’s quite a lot of airtime for a firm that doesn’t have nearly the same level of involvement in building cloud infrastructure. And, if you recall, Sony actually bought OnLive and Gaikai back in 2012 and 2015, respectively, only to shut them down. I’d be remiss to not suggest that maybe Sony’s campaign to block the deal proved irresistible for the CMA to ignore. More so, the term Game Pass appeared 168 times in the final report versus only 10 mentions of PlayStation Plus. It has the makings of a double standard.

The emphasis also clearly wasn’t on mobile. The fact that Apple, which has its own selection of lawsuits and challenges to its dominant market position, only appears a measly 12 times in this investigation where the target firm earns $2.6 billion in mobile revenue seems lackluster. Granted, counting doesn’t equate to qualitative insight. But it tells you how the watchdog allocates its attention.

What’s next, really

Even this negative result is unlikely to deter Microsoft from further deploying its cloud gaming initiative. Sure enough, it galvanized shareholders who’d like to see Microsoft divest its Xbox division and focus solely on enterprise-level software development. But so far Nadella has maintained his support for Phil Spencer’s games group.

There are at least three alternative scenarios. First and foremost is Microsoft’s already-announced move to appeal the decision. This still requires negotiating the $2.27 billion termination fee and it may take up some time (I’m hearing weeks not months but who knows) to finalize, and win, an appeal. It means its cloud gaming rollout will be slower but has not stopped.

Second, if anything, the outcome has lowered the value of two other potential acquisition targets: Take-Two Interactive and Electronic Arts. Valued at $21 billion and $36 billion, respectively, it is possible for Microsoft to try and buy one, or two, smaller publishers rather than a single big one.

And thirdly, the UK isn’t the global empire it once was. The EU is expected to issue its findings and decision on May 22nd, and the FTC’s lawsuit to block the deal will go to trial this summer. Microsoft can still very well prevail. That would mean formulating a specific version of Game Pass exclusively for the UK that does not offer any of the Activision titles. While impractical, Microsoft may be willing to accommodate it just the same, making it the CMA’s responsibility that UK gamers have depreciated access.

As for the regulator itself, it feels secure in the fact that it has done its job and has confidently blocked the deal.

Ignorant of its own ignorance, the watchdog moved the goalpost and failed to provide any real coverage of public responses by instead issuing an abbreviated summary of responses and statements by other game makers. The antitrust process takes place mostly behind closed doors and produces reams of obfuscated materials. It justifies its decision with a 418-page report that cannot be checked because of opaque research findings, offers a historically incorrect account of transformative technologies, fatally reinforces existing market structures, and gives a poor read on the future.

Speaking confidently in the absence of sufficient training data deserves greater scrutiny. Because this is a hallucination.

Wish I could like this twice. Regulatory action based on the imminent success of a hypothetical market that doesn't exist sets up a pernicious precedent for future decisions.

Bang-on analysis Joost. As always. 💪