Bigger means different

Four pro-competitive arguments in favor of Microsoft buying Activision Blizzard

The SuperJoost Playlist is a weekly take on gaming, tech, and entertainment by business professor and author, Joost van Dreunen.

What follows is an abbreviated version of my broader synthesis of the ATVI/MSFT merger. The full report, including the data, graphs, and all sources is available for download below.

Over the past months, I’ve spoken to a broad range of industry people, including both Sony and Microsoft’s legal teams involved in the case, financial investors, academic researchers, game developers, and publishers. I think it’s fascinating and a landmark merger.

From the top, I want to be clear that I have not been compensated by anyone to write this. It’s purely out of curiosity and a general sense of dissatisfaction with the overall debate, which, I think, is too narrow. The games industry is going through a transitional period and navigating it purely from the perspective of a single firm or franchise seems reductive.

Let’s jump in.

Executive Summary

The proposed acquisition of Activision Blizzard by Microsoft has four identifiable benefits. The deal will

Improve competition in the mobile games market. Adding a market participant that does not rely for the bulk of its income on mobile gaming will reduce incumbents Apple and Google’s negotiation position and positively impact the sector’s overall competitiveness.

Bolster a platform-agnostic future. Emphasizing cross-play functionality and catering to audiences outside of a platform’s own hardware ecosystem will benefit consumers and creatives.

Incentivize platforms to leverage more diverse revenue models. Large cross-platform operators will seek to maximize their return and cater to a more heterogeneous audience using a wider variety of monetization strategies.

Enable an overall healthier ecosystem. Greater visibility and accountability to business practices presents an opportunity to enforce better standards within creative subsidiaries and set the tone more generally for the ecosystem.

Market Landscape

Before addressing the CMA’s three theories of harm in detail, I’d like to provide an overview of the contemporary games market. (For an explanation of how I arrived at the following numbers, please refer to the section titled “Empirical Procedure” at the end of this document.)

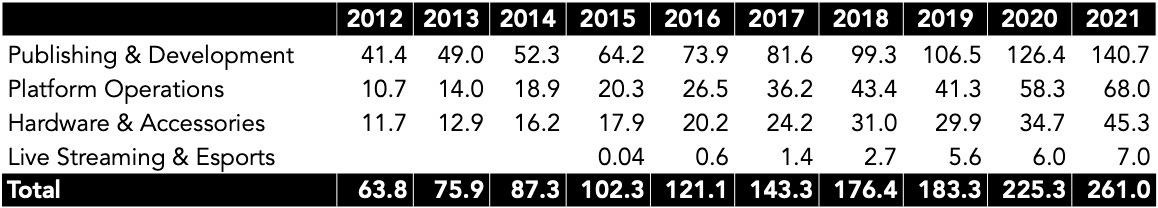

Succinctly, the conventional video games industry centered on a product-based business model in which developers, publishers, platforms, and retailers each operated more-or-less independently to offset the risk associated with the growing cost of development and marketing. This product-based business grew from $18 billion in 2002 to $64 billion in 2021, an increase of about 2.4 times. Over that same period, digital video game distribution has grown from virtually non-existing to $154 billion. By 2013, games-as-a-service—including revenue from free-to-play, micro-transactions, subscriptions, full game downloads, season passes, and digital expansions—surpassed the more traditional, physical business in size. This was the result of the ongoing penetration of broadband across households and the introduction of the smartphone, alongside the popularization of the free-to-play revenue model. Where previously platform holders and game makers had focused their efforts on the monetization of a narrowly defined, mostly homogenous demographic, a string of technological and business model innovations expanded the addressable market and introduced novel distribution and monetization strategies. As the games industry digitized, its existing value chain necessarily changed with it.

The fish have grown in size

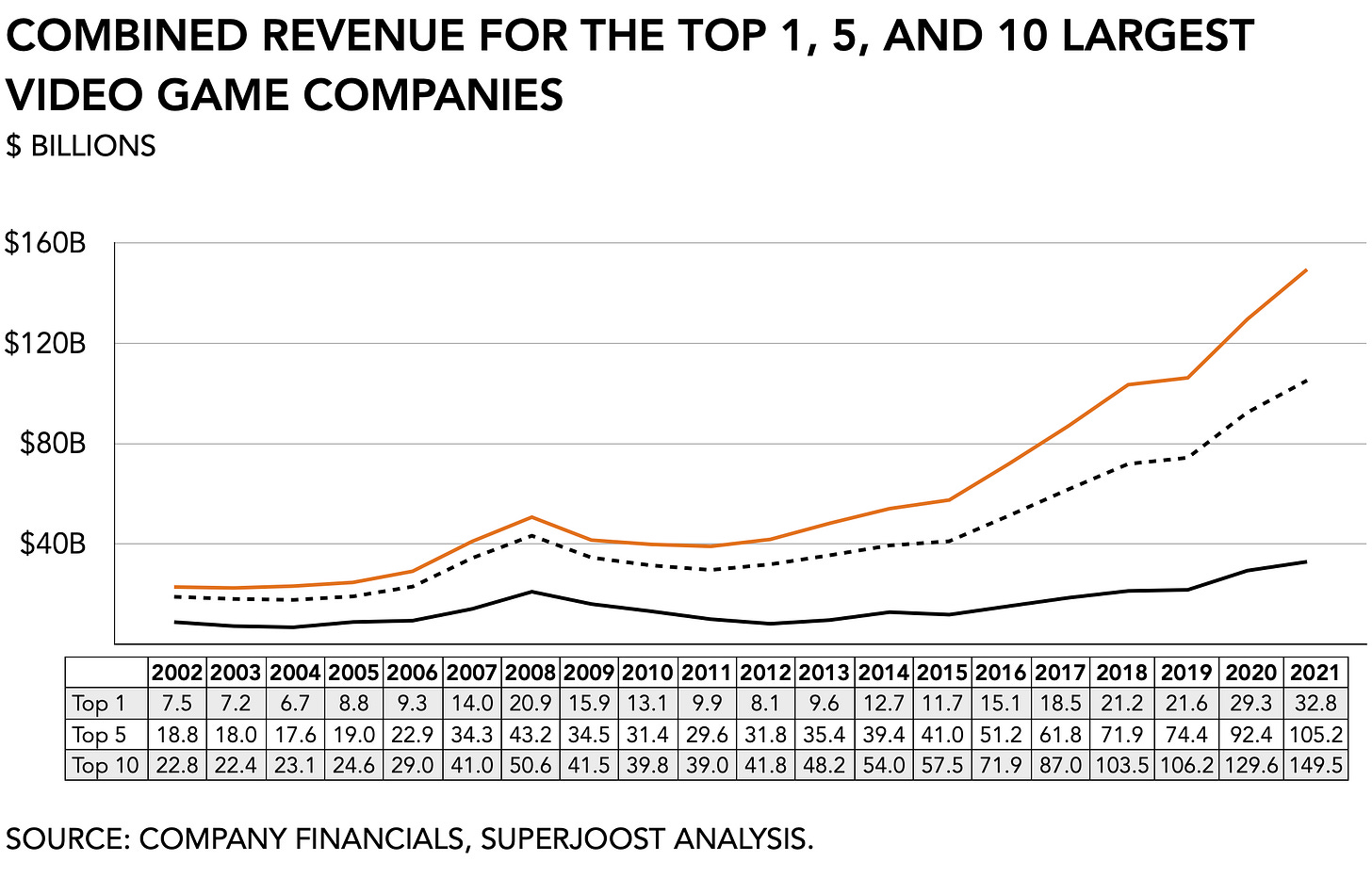

The size of the largest individual game companies based on revenue has increased over time. In 2021 the ten largest video game companies generated a combined $150 billion in revenue, an increase of 557 percent compared to two decades earlier when they earned an aggregated total of $23 billion. The largest five firms increased in revenue from $19 billion to $105 billion, a 458 percent jump. And the single largest game company in 2002, Sony, generated $7.5 billion. In 2021 the leader was Tencent with $33 billion in reported revenues for a 275 percent increase. Across the board, the largest firms in gaming have grown in size substantially.

The pond has grown, too

If we use the conventional market definition and combine revenues earned from Publishing and Development with Platform Operations, the video games industry has grown almost fourteen-fold from $15 billion to $209 billion in total annual consumer spending over the past two decades. The former, Publishing and Development, generates a total of $141 billion annually and is populated largely by companies that focus exclusively on the development, marketing, and distribution of interactive entertainment. Examples include Take-Two Interactive Software, NCSoft, CD Projekt Red, and Supercell.

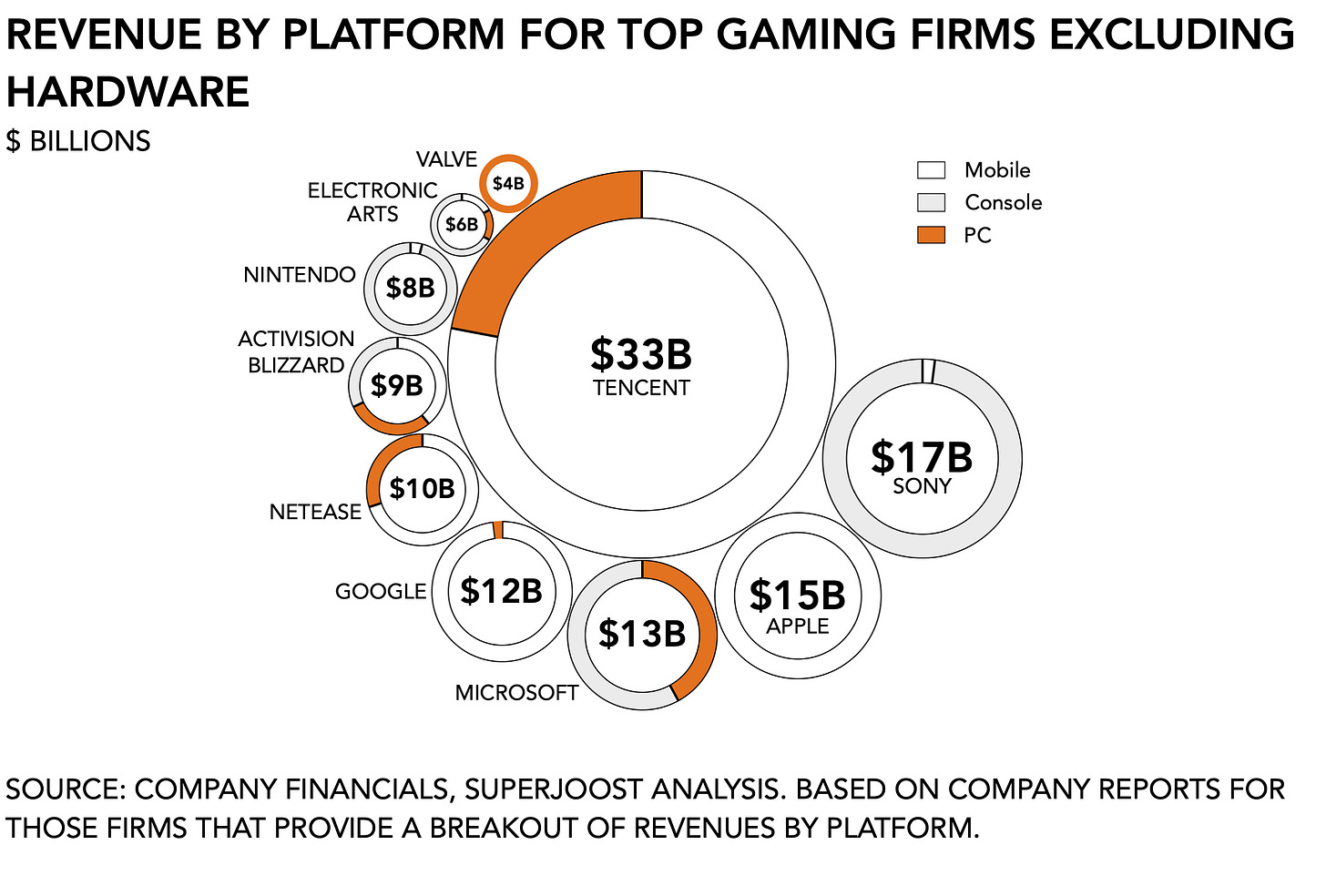

The latter, Platform Operations, generated a total of $68 billion in 2021 revenue from platform fees and related activity. Here we find mobile platform holders like Apple and Google but also more conventional console manufacturers like Sony, Nintendo, and Microsoft. On PC, Valve is the dominant platform holder but other smaller competitors exist in the form of Epic Games, GOG (owned by CD Projekt Red), and others. Several firms like Electronic Arts and Activision Blizzard do have their own storefronts, but these generally focus exclusively on a publisher’s own intellectual property.

The increase in consumer spending, both in time and money, has given life to a variety of adjacent markets, such as gaming accessories (e.g., high-end keyboards, controllers, monitors, headphones, and furniture), live-streaming, and esports. This allows us to consider a broader industry definition with new sub-segments that play a key role in marketing and monetization. Hardware and Accessories make the third category and generate $45 billion annually. Firms like Razer and Turtle Beach manufacture peripherals and accessories tailored to gaming audiences. This segment also includes graphics card manufacturers like NVIDIA and more general computer manufacturers like HP which operates in this category under the Voodoo and HyperX brands. Of course, console makers fall into this category as well, as all three incumbents generate income from the sale of their respective devices.

And finally, there is Live Streaming and Esports generated a total of $7 billion annually. This category is relatively new, relies on an indirect revenue model via ad sales and sponsorships, and is the smallest in size. Twitch and YouTube are the largest live-streaming providers and are best known in western markets. However, in Asia, there are several others, most notably Huya and DouYu (both majority owned by Tencent) and Bilibili (Sony holds a minority share of 4.98 percent). Other firms in this category create programmatic content (e.g., Modern Times Group) and participate in competitive events (e.g., FaZe Clan).

Table 1 Worldwide Video Game Industry Revenue by Activity

There also are new fish

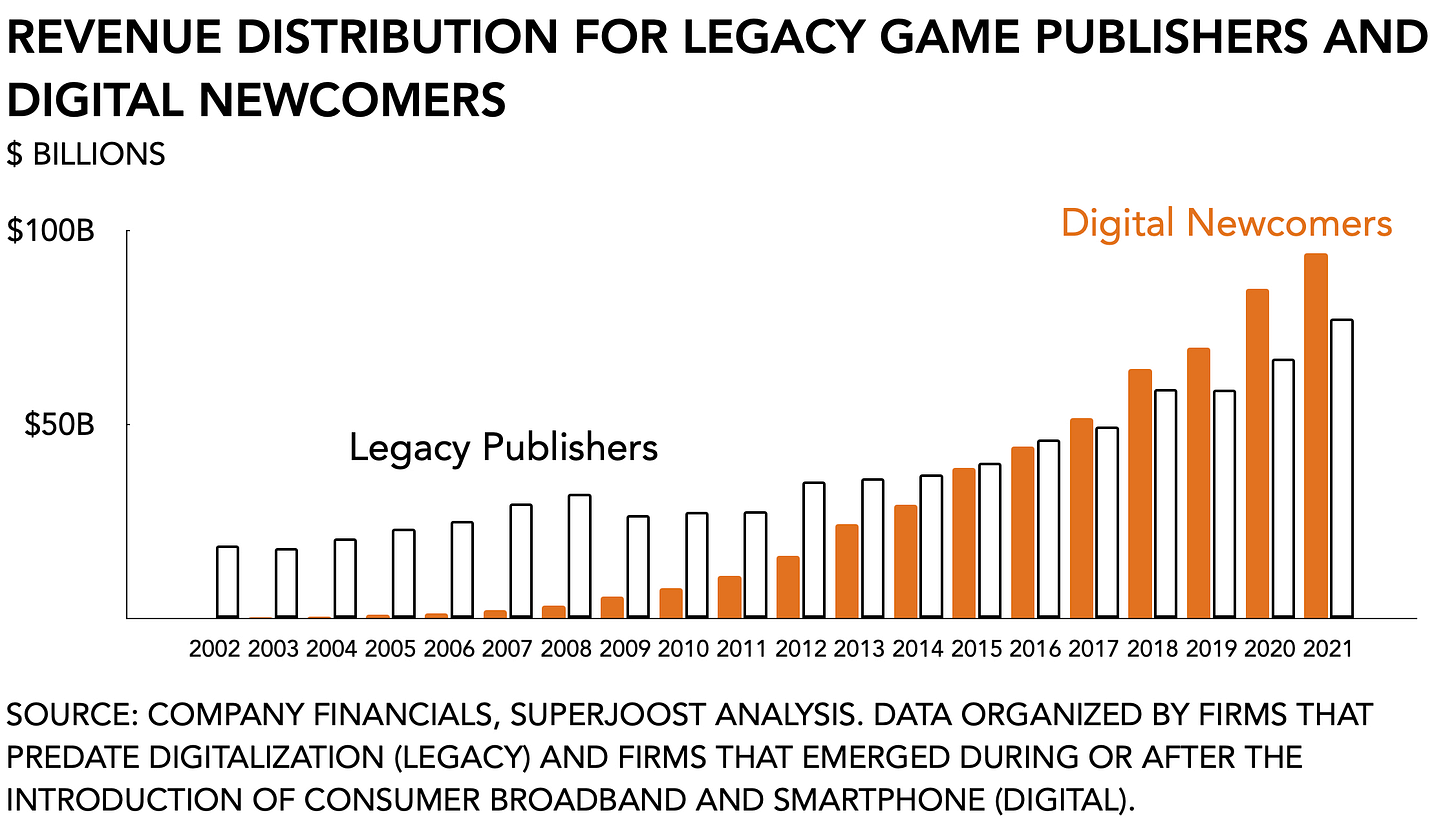

Newcomers have emerged that didn’t exist fifteen years ago. Digitalization and the popularization of the smartphone have vastly expanded the addressable audiences for interactive entertainment. It also made it much easier for a wider array of creative firms to publish their games. On PC, Steam, the biggest digital storefront, saw the release of no fewer than 11,581 new titles in 2021 alone, up from a few hundred a decade ago. Mobile app stores similarly experienced a massive influx of new titles and users, as CEO Tim Cook recently disclosed that there at no fewer than 34 million registered developers in the Apple ecosystem. Such growth has resulted in more widespread financial success, too. Specifically, in 2012, there were seventeen game companies that generated over a billion dollars in annual revenue. By 2021, that number was 52.

Many of these newcomers benefitted from the momentum created by the introduction of new technologies, most notably smartphones and digital distribution. Incumbent game makers necessarily move slowly towards novel innovations and distribution models as they stand to lose the most if a new device or platform does not catch on. During this brief period, while a budding ecosystem lacks apex predators, newcomers are able to swoop in and cement their position. The success of casual and mobile game makers like Zynga and King Digital ultimately forced legacy publishers to acquire them outright in order to secure a position in these emerging markets. Among the various digital newcomers, several notable ones originated in markets that had not played a significant role in the global business of games. Among them are Nexon and NCSoft (South Korea), Wargaming.net (Belarus), CD Projekt Red (Poland), and Tencent and NetEase (China).

Despite the largest 10 firms growing in size from $23 billion in 2002 to $150 billion in 2021 in combined revenues, their total market share in the global games industry has dropped from 90 percent to 57 percent over that same period.

And there are new ponds

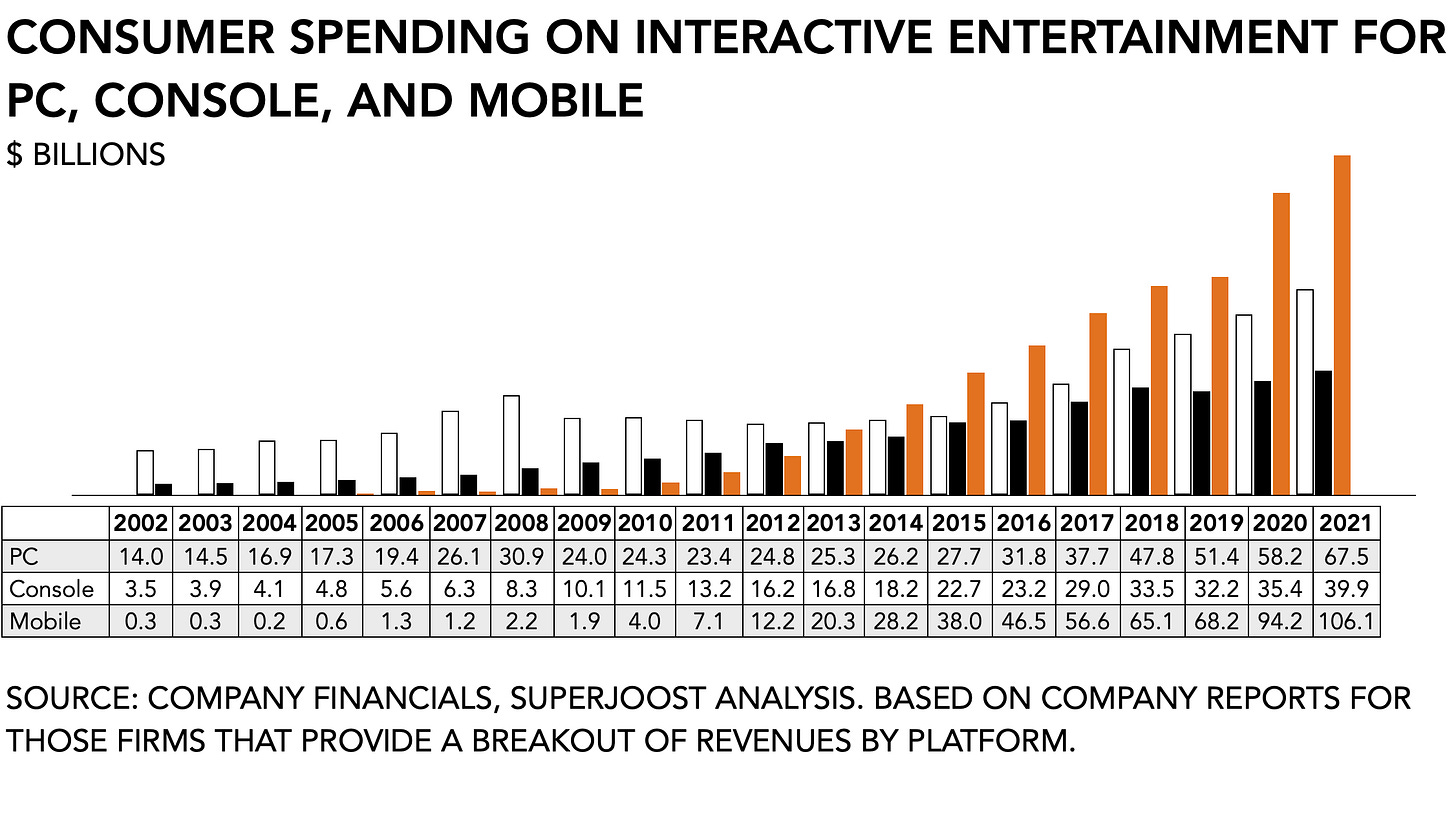

Console gaming used to be the entire market. After game makers had all but abandoned the PC market in the late 1990s, the console accounted for 95 percent of game publishing. However, digitalization managed to revitalize the PC market which grew from $4 billion in 2002 to $40 billion in 2021. And it needs little repeating that the mobile games market is the largest platform today, with $106 billion in consumer spending.

It is important to note that these categories are not mutually exclusive and, in fact, many of the largest firms operating in several simultaneously. The ability to publish content across several platforms and hardware devices simultaneously has facilitated recent blockbuster successes like Fortnite (Epic Games). Contrary to the conventional practice of releasing titles that are only compatible with a specific walled garden (ie. console), contemporary gaming audiences like to play and socialize across different devices.

Digitalization and the popularization of the smartphone have allowed the games market to grow tenfold since 2002. As a result, the industry has also changed in character due to the entry of new and different firms that today make up the overall competitive landscape.

In addition to an expansion in the total number of game companies, the increase in time and money spent on gaming among consumers has predictably attracted the attention of other, non-endemic firms. These include large tech firms like Meta, Netflix, and TikTok, which have each started development of content and distribution models. In addition, a growing number of fashion brands, sports franchises, music labels, and a host of consumer brands have begun investing in various games industry relationships and experiments to find traction with the growing audience for interactive entertainment. An influx of well-funded newcomers that rely for the majority of their income on business models unrelated to gaming and who have little vested interest in the gaming ecosystem itself and instead focus on short-term gains has the potential of eroding the industry landscape in the long term.

We may perhaps draw a parallel with an earlier, similar event in the history of the video games industry. The sudden interest in gaming in the 1980s, when Atari rose to infamy, resulted in a host of consumer electronics manufacturers releasing their own gaming consoles. It cluttered the market with undifferentiated content and alienated consumers. Subsequently, the video games market collapsed and did not recover until many of the would-be participants abandoned their gaming ventures. Only by ensuring quality for consumers and a measured approach to content production did interactive entertainment regain its appeal. It offers an important parallel with the current state of play as many firms are looking to claim market share but few have long-term vested interests in the health of the overall ecosystem.

Succinctly, interactive entertainment has grown substantially in size and, as a result, has added a variety of new market participants and segments. Despite the size of the proposed deal of $68.7 billion, contemporary market shares are relative. Post-merger, Microsoft would generate a total of $25.1 billion annually for an aggregate market share of 12 percent (up from 7.8 percent pre-merger), assuming a narrow industry definition totaling $208 billion annually. Using a broad market definition, totaling $261 billion in global revenue for the total market, Microsoft’s share reaches 9.6 percent post-merger (up from 6.2 percent). Microsoft’s global gaming market share post-merger is roughly the same as Sony’s ($24.8 billion) and smaller than Tencent’s 15.7 percent market share based on $32.8 billion in revenues and using the narrow definition.

Addressing the three Theories of Harm

Following its phase 1 investigation, the CMA identified three theories of harm (ToH) that it believes may meaningfully impact the structural makeup and long-term financial success of the different platform holders. They are:

ToH1a: Input foreclosure of rival console gaming platforms (excluding multi-game subscription services);

ToH1b: Input foreclosure of rival multi-game subscription services;

ToH2: Foreclosure of cloud-gaming service providers through leveraging Microsoft’s ecosystem.

The CMA has stated that in all three cases, Microsoft both has the “ability” and the “incentive” to foreclose on its rivals. Certainly, the threat of foreclosure, if Microsoft were to deny availability or parity of the Call of Duty franchise to any of its rivals in console, subscriptions, or cloud gaming, needs consideration. The evidence supports that Call of Duty is a popular franchise that attracts a broad audience.

With regards to ToH1a, legal scholars skeptical of the proposed acquisition have argued that under EU Competition Law vertical input foreclosure as it relates to game genres should be considered in assessing relevant theories of harm. The argument comes down to Microsoft gaining near-monopolistic power over certain genres (e.g., the first-person shooter category where Call of Duty is a leading title), which will therefore both deter competitors and disincentivize Microsoft itself to continue innovating.

That argument may make sense in a marketplace in which a product-based business model is the most prevalent. Denying access to premium content as competitive leverage has, in fact, been a long-standing practice in the games industry where exclusivity served as a key economic principle in the conventional razor-blade business model. However, in a service-based market environment, where game makers seek to gradually monetize players in the case of free-to-play games and recurrent payments in the case of subscription-based titles and services, the cost structure differs.

The immediate cost at a purchase price of $68.9 billion means Microsoft is paying an extra $19 per share above Activision Blizzard’s current share price of $76. As such it is motivated to make its content available to a wide audience. Moreover, because of the deep multiplayer gameplay mechanics, Microsoft is disincentivized to reduce the size of its target audience because it would erode existing positive network effects (e.g., ensuring sufficient availability of other players to ensure short wait times for players to join). Reducing access will make it harder for Microsoft to break even on the deal price.

Aside from the upfront expense of developing a game, publishers also have to maintain servers to facilitate gameplay, commit themselves to the ongoing development of expansions and new content acquisition, and continuously spend on marketing to acquire new users and retain existing ones. Dominance within a single genre has, moreover, not proven to provide permanent insulation from other exogenous circumstances, including the changing preferences of players, the popularization of novel gameplay types, changes in regulatory policy, and player toxicity. For example, Riot Games which publishes League of Legends, a multiplayer online battle arena, or MOBA, managed to accumulate well over 125 million monthly active users. It proved so popular within its genre that industry observers questioned whether MOBAs were even a genre at all since Riot dominated it so effectively and disallowed any other publisher from taking significant market share. With the exception of Valve’s DotA 2, would-be competitors like Infinite Crisis (Warner Bros.), Heroes of Newerth (Garena), Smite (Hi Rez Studios), and Heroes of the Storm (Activision Blizzard) failed to capture sufficient market share and many were ultimately discontinued. Even so, Riot Games announced seven new projects based on its IP including, VALORANT, an online shooter title that has become competitive to both Activision Blizzard’s Call of Duty and Overwatch franchises. And, a generation before that, World of Warcraft (Activision Blizzard) eventually saw its market share dwindle despite its dominance in the subscription-based multiplayer online game genre as a novel revenue model, free-to-play, rose to popularity. Service-based game publishing is based on different economics than the conventional product-based model.

With regards to ToH1b, attributing ownership of a single key franchise like Call of Duty to an all-encompassing and unfair advantage does not rhyme with several adjacent entertainment markets. First, the video streaming platform Netflix initially only developed a digital distribution platform as an add-on to its existing physical business and managed to become a leader in the category during its early stages. It also encouraged other media firms like HBO, owned by Warner Bros. Discovery, and the Walt Disney Company to develop their own streaming services. In the fall of 2017, Disney discontinued its content licensing deal with Netflix, forcing the latter to start developing its own original film productions and television series. It resulted in the rapid development of several high-quality video streaming platforms that offer premium, exclusive content at a low consumer price. Today, there are a myriad of services available to consumers, including Amazon Prime Video (launched in 2016) with more than 200 million subscribers, HBO Max (2020) with 74 million, Paramount+ (2021) with 56 million, and others including Hulu, Discovery+, Apple TV+, and Peacock with fewer than 50 million each. Each of these platforms relies on content that is available across several of them as well as exclusive intellectual property. The emergence of, and by some accounts replacement of conventional television consumption by, streaming video has been both a boon to content creators and price-conscious consumer audiences. It seems unlikely that a single shooter franchise like Call of Duty will make a difference in the long run any more than a single sci-fi series will foreclose any video streaming provider without continued investment, content acquisition, and development. From a consumer’s perspective, given the overwhelming preference among audiences for subscription-based content services, simultaneously releasing new content as a stand-alone premium game and as part of a subscription service, is the better deal. Conversely, it seems counter-intuitive for any platform holder to insist on monetization and distribution models that cater to their existing content creation strategies instead.

Second, from the perspective of the broader creative ecosystem, the CMA itself recently ruled it “unlikely that a competition intervention would improve outcomes overall,” and it had an increased likelihood of resulting in “unintended consequences and worse outcomes for both consumers and creators.” In its analysis, the CMA exhibited the relative market shares of various music streaming services available to UK consumers, indicating Spotify as market leader with “50-60%”, followed by Amazon with “20-30%” and Apple with “10-20%”. It is odd that in order to create a broader, more competitive ecosystem in one entertainment industry (cloud gaming), structural remedies are necessary for fear of diminished capacity among content creators to negotiate better contracts and make more money, while simultaneously arguing in another (music streaming) that it is, in fact, the disproportional distribution of revenue resulting from a relatively small number of artists being successful as a fundamental reason why it is difficult to earn a living in entertainment post-digitization. It would be inconsistent to rule differently on such a similar matter between related (entertainment) industries, especially two that feature several participants that would ostensibly be affected by the proposed acquisition (e.g., Sony, Apple, Google, Amazon).

With regards to ToH2, building the necessary infrastructure that can successfully facilitate both the digital distribution of single-player gaming content and multiplayer gameplay is unlike more conventional modes of media consumption. Video and music streaming, for example, rely on third-party content delivery networks, or CDNs, (e.g., Akamai, Amazon, CloudFlare) to ensure rapid connectivity. An important difference is that the quality of the stream (ie. resolution) may vary depending on the local network speed for an end-user and, once established, the quality will improve as the system has a chance to catch up.

For video games, however, latency has to be consistent and low. A choppy connection between a player and a game server impacts their ability to participate on equal footing with others. Especially in fast-paced action games like Call of Duty, a fraction of a second can make the difference between winning and losing. The popularity of online multiplayer games, combined with a free-to-play or subscription-based revenue model, means that contemporary game companies aim to attract a large audience that monetizes only marginally or gradually. According to one study, this amplifies “the impact of network conditions on quality of service and player satisfaction.” A bad network connection with high latency exacerbates player churn and undermines their accompanying monetization strategies.

However, in the video games industry, there are examples of successful publishers investing in upgrading their available infrastructure to better serve their players. In 2015, Riot Games sought to improve its latency issues which it had identified as a deterrent for its players. Unable to rely on third-party infrastructure, the firm effectively established its own internet backbone to reduce interruptions to a minimum and provide the best possible play experience. An observant reader will be reminded of my previous mention when Riot Games saw itself forced to innovate and develop novel content despite its dominance in the MOBA genre. In the case of Riot Games, it concerned only one specific title and not a range of hundreds of different games with different play styles. As a result, the initial investment in infrastructure is substantial and requires ongoing improvements. It is perhaps why some of the major gaming platform holders today are hesitant to commit and prefer to find new ways to exploit their intellectual property in new ways. Alternatively, existing game publishers have pulled their games from smaller streaming service providers. NVIDIA’s GeForce ran trials with Bethesda and Activision Blizzard which both ended with the removal of their content due to a disagreement on how to monetize the service. In effect, the early-stage economics of game streaming services prohibits content from reaching consumers. Conversely, disincentivizing infrastructure-focused companies is likely to result in poor latency and other shortcomings in quality, thereby disadvantaging consumers and creatives.

Bigger Means Different

A healthy ecosystem for game makers and players is critical to the industry’s continued growth and sustainability. Providing organizations with incentives to invest in the development of an accessible, inclusive, safe entertainment market will benefit consumers, especially at the dawn of a new technological transition. I’ve identified four benefits to the overall gaming ecosystem and consumers at the core of the proposed acquisition.

Improved competition in the mobile games market

Mobile gaming is the largest segment with $106 billion in total revenue in 2021. Yet it is governed largely by two platforms: Apple and Google. Both firms almost exclusively rely on platform fees for their income. Apple, however, launched its own mobile gaming subscription service in 2019, Apple Arcade, which is expected by some estimates to generate $1.2 billion by 2025. Assuming similar growth across the category, that means the firm’s first-party content will account for approximately less than 6 percent of its annual gaming revenues. First-party content is more profitable for Apple. Recent research indicates that following a period of relying on third-party content providers, platform holders across different ecosystems shift their policies to become more selective and geared toward end users, which are associated with shifts in complementor performance outcomes. Effectively, platforms edit their policies in ways that benefit their own titles and disadvantage those of third parties. Here, Apple has been known to re-write existing platform policy to advantage themselves at the expense of third-party complementors. This currently presents a weakened negotiation position for small and medium-sized game makers who rely on these platform holders for access to their audience. In the absence of a strong rival, the dominance of Apple and Google over their respective mobile game markets will increase.

However, with ownership over Activision Blizzard’s mobile titles—Call of Duty Mobile, Diablo Immortal, Candy Crush, and others—Microsoft, as a direct competitor to Apple and Google, will gain a considerable stake in the overall mobile gaming ecosystem. Specifically, based on Activision Blizzard’s earnings reporting for 2021, Microsoft would gain $3.2 billion annually in mobile gaming revenue, roughly equivalent to 3 percent of the global mobile games market. If we exclude Apple and Google, which earn almost exclusively from platform fees and significantly less from game publishing, the acquisition makes Microsoft the third-largest mobile game maker behind Tencent and NetEase. It results in an improved negotiation position in comparison to an independent Activision Blizzard, which relies for a combined 34 percent of its earnings on Apple and Google (17 percent each), up from 15 percent and 14 percent the year before, respectively. Both Apple and Google will have to negotiate with a third-party complementor that is much larger, more powerful than any individual game publisher, and doesn’t rely for 39 percent of its annual income on just two mobile platforms.

Enabling greater competition between platforms is consistent with the CMA’s own announced investigation in the “mobile browsers and cloud gaming” ecosystem, where, it states, Apple and Google “hold all the cards.” Entry into mobile by Microsoft through the purchase of Activision Blizzard would ameliorate the circumstance of only two firms controlling the mobile gaming space, especially considering both Apple and Google pulled Fortnite from their respective app stores because its publisher, Epic Games, offered an alternative way for players to pay for in-game items. Even a game publisher as successful as Epic Games has so far proven unable to budge either platform holder, suggesting that even the most popular content is not going to convince them to accept changes to their ecosystem that, in the case of facilitating alternative payment options, would benefit consumers.

Finally, Activision Blizzard’s mobile division performed well during its most recent earnings, reporting a 20 percent year-over-year increase in net bookings versus a 13 percent decline in worldwide spending on mobile gaming. According to the firm, its Candy Crush franchise saw an increase of 8 percent in net bookings year-over-year along with contributions from Diablo Immortal and an optimistic outlook for the near future. This momentum will allow Microsoft to bring other owned IPs to mobile via cross-promotion, and potentially strengthen its negotiation position with Apple and Google with regard to transaction fees that will benefit consumers.

Bolster a platform-agnostic future

Central to the contemporary expression of online multiplayer games is the enablement of consumers to play with anyone on any platform. Akin to telecom operators allowing people to communicate (e.g., voice, text) with each other irrespective of their preferred service provider, cross-play promises a platform-agnostic future in interactive entertainment. This is a deviation from the conventional console gaming model that prescribes certain content to only be available on specific hardware. As a platform holder, Microsoft is better able to negotiate with other platforms to facilitate cross-play functionality than any individual game publisher would be.

Previously it took the massive success of Fortnite to, eventually, convince platform holders to enable cross-play across all devices available in the market. Notably, Apple and Google did not object to facilitating Fortnite, even if they later ended in court with Epic Games on the issue of providing consumers with a choice in payment options. Here, Sony was the last holdout in enabling cross-play across all devices. Incumbent console makers, Nintendo and Sony, have only recently started to explore cross-play functionality and digital distribution of their proprietary intellectual property. Nintendo, for instance, uses mobile as a marketing tool to drive business to its own hardware ecosystem. Despite several attempts to release more mobile gaming content since 2016, when it launched Super Mario Run on mobile platforms, Nintendo announced just last week that it was shutting down the development of Dragalia Lost, its first original mobile intellectual property. Similarly, it was not until Sony acquired Savage Game Studios in August of this year that the firm founded its PlayStation Studios Mobile division.

The reluctance to create content for a rival platform is understandable. Conversely, approval of the proposed deal would send an encouraging signal to platform holders emphasizing cross-play functionality and catering to audiences outside of a platform’s own hardware ecosystem.

Incentivize platforms to leverage more diverse revenue models

As a game maker, Activision Blizzard is currently less capable of monetizing its IP using a broader variety of payment strategies. Despite its reach and success, for instance, it has never supported live streaming services (e.g., OnLive, Xbox Game Pass) nor made its content available via a subscription service similar to EA Play (Electronic Arts) and Ubisoft+ (Ubisoft). Keeping content exclusive or at a prohibitive price point means fewer people get to play it. Microsoft will be in a better position to cater to a more heterogeneous audience by using a wider variety of monetization strategies.

Here, too, incumbent console makers have been remiss in developing a broader variety of content offerings and price points. Arguably, it wasn’t until Microsoft’s Xbox Game Pass subscription started to do well that Sony decided to update its PlayStation subscription and offer more diverse. price points and packages to accommodate a broader audience. For creators, a subscription offering can provide exposure and convince players to try out new content in ways that have previously been unavailable. It is common practice to bundle popular content with less well-known offerings to compensate for the difference in visibility. Given the strong consumer preference for low-risk tryouts, followed by downstream monetization, especially smaller developers will have a better chance to gain access to audiences. A strong content library will allow platforms to lower prices across the various distribution channels and force incumbents to follow suit.

Enable an overall healthier ecosystem

The Dutch have a saying that goes “tall trees catch a lot of wind” to refer to the higher degree of scrutiny received by more prominent people or companies. Small organizations can get away with bad habits and poor treatment of their workers, but for large ones that is much more difficult. Now that interactive entertainment has come to occupy a more prominent role both as an employer and a cultural industry, the many systemic bad behaviors that have characterized the business of video games for years will need to be addressed. It must be held to a higher standard to ensure a minimum of well-being for its many employees and players. Greater visibility and accountability to business standards create an opportunity to enforce better standards within creative subsidiaries and set the tone more generally for the ecosystem.

On the supply side, the games industry has a documented history of sexual harassment, gender discrimination, and workplace toxicity. Employees at other firms have suffered the same, such as Riot Games, which was recently ordered to pay $100 million in a gender discrimination case, and Ubisoft was sued for “institutional sexual harassment” among others. That is unfortunate and needs to change. A high dependency on the success of one or only a few titles may inspire unusual labor practices, uncommon incentive structures, or even turning a blind eye to harmful working conditions in pursuit of profitability. De-risking a game publishing business model through the exploitation of employees by, for instance, squeezing them for extra working hours to get a title out on time is more likely when an organization disproportionally relies on one or a few titles for their financial success. As we learned from its latest annual report, Activision Blizzard publishes several franchises, but it is Candy Crush, Call of Duty, and Warcraft that represent 82 percent of net revenues. Similarly, the overly aggressive monetization tactic of loot box monetization may be read as an unscrupulous attempt to drive profitability in the near term and satiate quarterly reporting metrics, while disregarding the long-term negative impact.

On the demand side, better management of bad player behavior and toxicity in online environments would go a long way to safeguard players. Exposure to cyberbullying and sexual and racial harassment has a strongly negative impact on the overall experience and can quickly erode a gaming community’s social fabric. Both the performance of individual players and online teams has been found to suffer as a result of toxic behavior. Furthermore, recent research confirms that toxic behavior towards game developers tends to be higher in the highly popular categories of competitive and multiplayer online games. The games industry acknowledges the importance of addressing toxicity for the sake of its players and obviously also for its own continued success. Addressing these issues to ensure better work environments, safer online play spaces, and adequate monitoring and management of unwanted behavior will benefit consumers and creatives alike.

The $261 billion video games industry today is bigger, more complex, and caters to more people across more devices. The promise of increased competition in the mobile games market, a bolstering of platform-agnostic gameplay, further diversification of distribution and monetization models, and increased efficacy in dealing with poor practices both among game makers and game players will be to the benefit of all. Contrary to leaning on existing and gradually outdated business models situated within walled gardens and focused on profit maximization of a subset of consumers, the future of interactive entertainment will be founded on more competition between platforms and devices. Play is an important part of the overall health of a society. Ensuring properly motivated, accountable, and capable firms participate in an adequately competitive marketplace will ameliorate several of the bad habits found in the games industry today. Breaking down unnecessarily restrictive rulesets between minimally cooperative platform holders and providing incentives for industry participants to invest in infrastructure and services are key to ensuring consumer welfare and a thriving future for the video games industry.

Thank you Joost! Amazing write up of the situation and the overall industry dynamics..

While the headline is your compelling argument in favor the ATVI/MSFT deal, your succinct games market summary is superb. I will attribute and borrow heavily from it as I write our company's annual letter over the holidays. TY Joost!

[One small typo: "Console" and "PC" are accidentally reversed in your Consumer Spending table.]

Now that the USMNT was eliminated, I am all in for the Oranje! 🧡