Engine failure

Can game makers put Genie back in the bottle?

Middleware is sexy as hell, is what I always say.

Often, the unsung toolset that makes it possible to build the universes in which we play is the software engine, the foundational codebase that makes up the interactive world. New features expand creatives’ ability to dream up novel experiences. It is fundamental, yet the least understood category. That’s the lesson I take from this week’s stock drop.

On Friday, Google’s release of Project Genie, a prompt-based AI solution that generates explorable 3D environments, triggered the sell-off of several prominent game makers’ shares.

That’s entirely too soon, as I don’t expect people to start spinning up their virtual universes quite yet for a few reasons.

First, established publishers have been at this for a while, and even their worlds lose their appeal. It’s no secret that Ubisoft, which has been making all manner of more-or-less historically accurate environments, has been struggling financially. Here’s a legacy game maker with strong IP and more French people with art degrees than you can throw a baguette at, yet it’s having a terrible time innovating. That’s too bad, of course, and evidence of why the idea of instant open-world games is going to be difficult to realize.

Second, creating compelling game worlds is harder than it seems—much like how AI can’t simply prompt its way to the next great American novel. Developers like Rockstar spend such attention to detail that their games, like Red Dead Redemption II and Grand Theft Auto 5, hold up extremely well, even a decade later. Part of the secret sauce is building proprietary engine software. It is this combination of in-house tools and incredible talent that makes it possible.

And even then, it’s not a given. Ubisoft employs 17,000 people who do this for a living, and even they struggle to consistently generate universes that captivate players. The creative vision required isn’t something you can commoditize through better prompts.

Third, Genie is currently only available to Google AI Ultra in the US, which costs you $250 a month. While I’m enticed by the idea of creating my own private playable environments, I’m going to forfeit the opportunity and have professionals make me something instead. For that kind of money, I can buy three copies of GTA6 and a sandwich.

Navigating these AI-generated worlds also happens at a measly 24 frames per second. That makes for great prototyping and clever demos. But a fully immersive interactive experience it is not.

The immediate counter-argument is, of course, that prices will come down, and that in a year or five, from now, we’ll all be quietly snickering at home in our own custom adventures.

I think it’s unlikely.

People enjoy agency but only for the fun parts. Ask yourself how much time you’re willing to spend deciding what to watch on streaming video. Between a dozen providers and hundreds of shows, audiences are often exasperated within minutes of having to navigate, decide, and commit.

Remember when sneaker companies made it possible for people to custom-design shoes on the internet? Yeah, that went nowhere. People like it when professional creatives make something marvelous for them. You are the wizards. Show me some magic!

The real challenge, however, is economic.

In a recent article, Tim O’Reilly argues that the current issue with many of these consumer-facing AI applications is that, yes, supply is coming online, but demand is not (h/t Bill Grosso). An economy requires production matched to a consumer base willing to pay for it because it provides value. And demand, in turn, requires both capital and time to purchase and enjoy. It’s something that Henry Ford understood: mass production requires mass purchasing power, which is why he raised wages and created the weekend leisure economy.

AI has yet to provide a clear answer to any of this. Consumers certainly have no love for AI-based games. Recently, Enzoi, a Sims competitor, initially sold well, but the abundance of clearly AI-generated items and characters quickly became a thorn in players’ sides. Demand, in other words, isn’t quite there.

Beyond an initial aversion to AI slop in games, there is also an abundant inventory already available. Platforms like mobile app stores and Steam are absolutely cluttered with content. Selling into a vacuum is one thing. Flooding an already saturated market with cheaply produced, undifferentiated products is hardly a winning strategy.

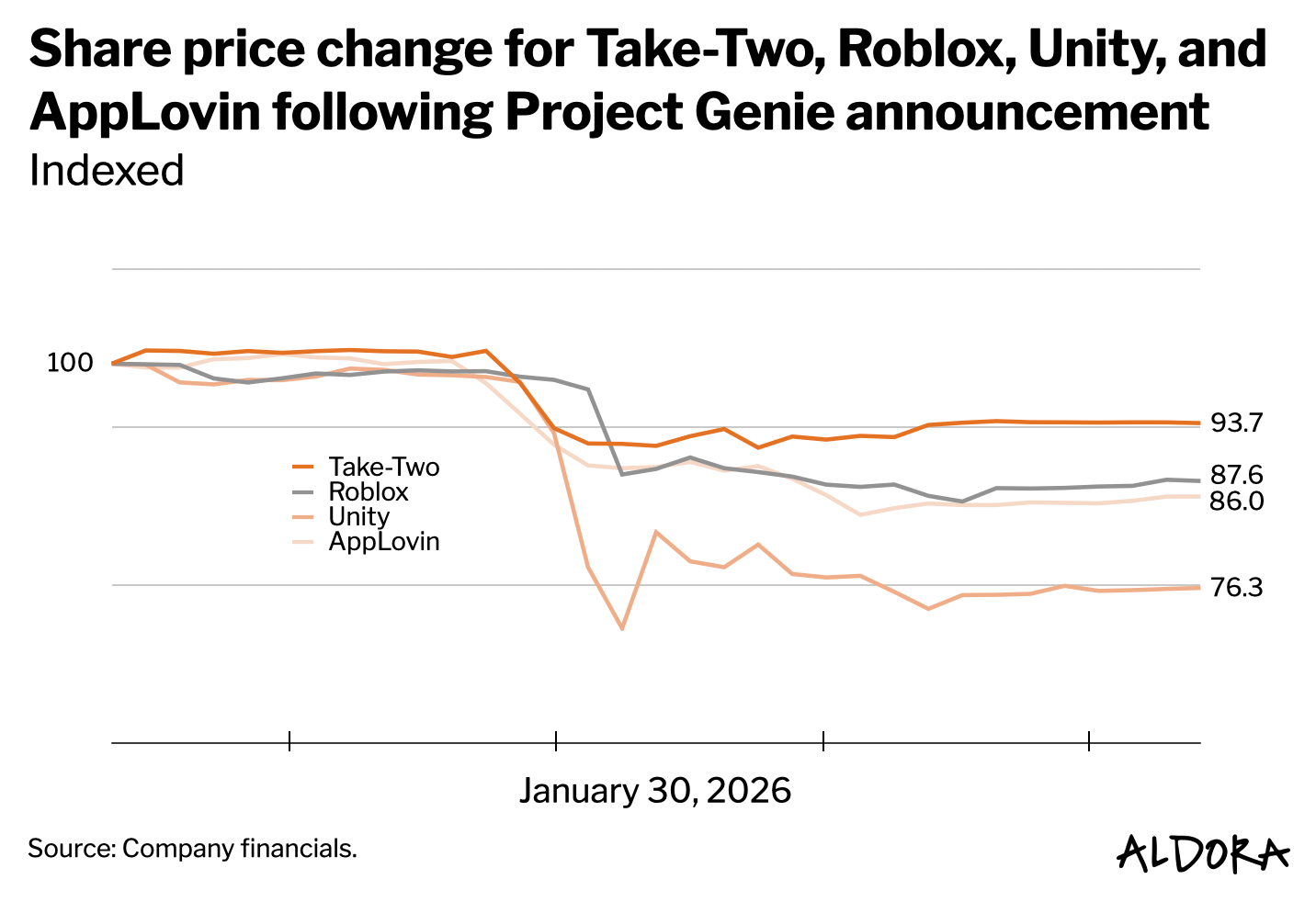

Nevertheless, Wall Street’s immediate response to Project Genie’s release was a massive discount to several of the most prominent gaming companies. Specifically, Unity was down 24 percent, Roblox 14 percent, and Take-Two Interactive 8 percent. AppLovin, an industry star, saw a 17 percent drop in its share price, despite its user acquisition offering being an obvious panacea for the current content glut.

It’s true, of course, that game makers find themselves in a strained period. Despite overall consumer spending rising again in 2025, the underlying trend is that more revenue is coming from a smaller, more affluent group of players. It means that everyone is catering to the same minority among the overall consumer market and raising prices.

At the same time they’ve started increasing prices, publishers have also spent the past year focused on margin improvement: cutting overhead and deploying AI solutions in costly development areas. In this context, worldbuilding is hardly new—procedurally generated environments have existed for years. What’s changed is that newer AI tools lower entry barriers, creating competitive pressure for incumbents who’ve relied on proprietary toolchains as moats.

Novel technology is named after what came before. The current iteration of middleware is squarely in the “horseless carriage” phase. Applications mostly replicate existing ideas and gameplay patterns at a lower cost. We’ll see real transformation when AI-based design creates experiences that are uniquely its own, not just accelerated versions of traditional workflows.

But for now, investors are trying to price in any efficiencies that may emerge as the value chain consolidates and reduce overhead to improve margins.

Meanwhile, studios face a predictable, strategic question: build proprietary AI capabilities internally as a differentiator, or buy commodified solutions? Most can’t afford to develop tools that provide a genuine competitive advantage—particularly after venture capital’s retreat from gaming over the past year. It pushes the industry toward off-the-shelf infrastructure.

And that’s fine. In creative industries, differentiation comes from compelling content. The industry at large finds itself in a period centered on distribution innovations and novel pricing models. Based on my theory, the Play Pendulum, we’re still a few years out from technology disrupting and evolving content creation. In the current market, companies likely to thrive are those that use AI to lower production costs and invest the savings in what truly matters: creative vision, world design, narrative depth, and the intangible elements that make experiences memorable.

The market panic assumes that AI will replace creativity. The more likely outcome is that AI will raise the stakes for creative differentiation. Studios with strong IP, established player networks, and creative talent will adapt. Those relying primarily on technical execution as their moat will struggle.

It only feels like AI is showing up now to disrupt gaming, but it’s actually a comparatively old and integrated toolset. My NYU colleague Julian Togelius published his first book on AI and games back in 2018, and the industry has been experimenting with these approaches for years. When Togelius began his PhD in 2004, he presented his work on evolving neural networks to play racing games to executives at Electronic Arts and Microsoft Game Studios. Their response? "AI and games don't go together. We don't need this." Two decades later, the market is having the exact same panic.

🎙 You can find my full conversation with Julian here.

His most recent book, Artificial General Intelligence, takes a critical look at how game developers define and apply this technology. He makes the case that the future of AI isn’t about building ever-larger general models but about creating specialized systems optimized for specific domains, a perspective I share.

This historical context reveals a pattern: the gaming industry consistently overestimates AI's near-term disruption while underestimating its long-term integration. It offers some much-needed context to counter the sudden panic around Project Genie, which assumes AI is about to replace game development.

Unity CEO Matthew Bromberg's response to Project Genie reframes the entire conversation. Rather than viewing world models as an existential threat, he positions them as input for Unity’s deterministic execution layer. Or, as he puts it:

“Video-based generation is exactly the type of input our Agentic AI workflows are designed to leverage—translating rich visual output into initial game scenes that can then be refined with the deterministic systems Unity developers use today.”

In other words, AI-generated environments become raw material that Unity’s engine converts into structured, controllable simulations with physics, gameplay logic, and monetization systems. World models expand content supply, and engine providers like Unity remain the system of record for runtime and distribution.

It is a dynamic that actually broadens the addressable market rather than threatens it. During a fireside chat with Matthew last semester, he told me that a primary directive for Unity is to democratize game development. It is a vision he shares with his colleague and rival, Epic Games CEO Tim Sweeney, who’s in charge of the other major software suite, Unreal Engine. AI accelerates environment generation while engine providers focus on what developers actually need: reliable, repeatable, monetizable experiences.

The real limitations are economic and creative. As Togelius notes: “You can use Gemini or Claude on the backend, but that’s going to be really expensive, and it doesn’t work with economic models of games because you’re going to have to pay several cents for every conversation.” More fundamentally, AI-generated content requires more authoring, not less: “Instead of authoring four lines of dialogue in a dialogue tree, you have to author an entire world.”

Studios with strong IP, established player networks, and creative talent will adapt by using these tools to lower production costs while investing savings into what actually differentiates them. In contrast, those relying primarily on technical execution as their competitive moat will struggle.

World models like Genie represent meaningful progress in content generation. But they can’t replace the creative vision, narrative depth, and intangible elements that make games memorable. If anything, they raise the stakes and force creatives to find their voice and realize their vision as a critical part of what distinguishes them.

The new medium thesis and the demand problem aren’t mutually exclusive. The opportunity is real, but it only materializes if the first wave of experiences is genuinely compelling enough to pull people in, not just technically impressive enough to impress investors.

Until then, somewhere in Silicon Valley, an AI is generating its 47th billion procedurally-created medieval tavern, each one slightly more beige than the last. Progress.

The horseless carriage phase will pass. When it does, the winners won’t be those with the fanciest AI tools. They’ll be the ones who used those tools to make something genuinely worth playing.

Agreed that AI will not destroy creativity, but will force creatives to lean in on unique experiences which, hopefully, will be sustainable for devs and valuable to players in the long run.