What follows is Part Three of a series that looks at the next 10 years in gaming. The emphasis is on the formulation of novel strategies and business model innovation. Previously, in part One, I laid out the 2021 Video Game Flywheel, and Part Two covered the Rise of Recurrent Revenue.

My thesis for the coming years is that “More is Different.” Creative firms confront a changed market environment today because video games are now a mainstream form of entertainment. Beyond a much larger addressable audience, there is ample access to cheap capital, a slew of incumbents and new platform holders eagerly buying up intellectual property, and a lot of activity around acquisitions and IPOs.

Because of the sheer size of the market, game makers can now monetize audiences in ways that are both similar to practices found in conventional media and via novel revenue models.

This week’s topic: advertising.

Ad dollars looking for a new home

All the way back in the 1930s Procter & Gamble started financing daytime serial dramas on the radio. Its objective: sell more soap. To grow its business, P&G invested in the creation of content that specifically targeted an audience of (then still) housewives. Because of its association with its various soap brands (e.g., Oxydol, Duz and Ivory) a new genre emerged: soap operas.

Remarkably, the games industry has been mostly unaffected by advertisers. Unlike every other form of entertainment, video games have managed to abstain a reliance on ad dollars for most of its history.

But that’s about to change.

It is no secret that ad revenue for linear media has started to crumble. Audiences are aging, migrating to other, newer ways to consume content, or both. Only by the grace of 2020 being an election year did annual spending on broadcast TV decline by only -3%. Key categories like sports had a much harder time: after initially looking forward to a +5% increase in 2020, it ended up -30%.

That certainly doesn’t mean the money is gone. P&G still wields a $11 billion annual advertising budget. It just tells you that not all of that $75 billion is going to broadcast TV anymore. Advertisers are sobering up to the idea that, perhaps, they should review how they allocate their marketing budgets to reach the right consumers. In response they have been placing small bets on novel channels and content, including video games.

At the same time, there is a strong push by adjacent categories to move away from advertising revenue. Video and music have been aggressively pushing into subscription-based streaming models rather than remaining at the behest of brands.

But the question to ask, however, is why would game companies accept ad dollars now?

For years advertisers have been trying to get into games. Some of the more recent outgrowths of this experimentation can be hilarious. We’ve seen a gaming console that cools beer, another that keeps your fried chicken warm, and a bunch of other gags. But the relationship goes back a lot further. In 2005, Sony struck a sponsorship deal with Pizza Hut. By typing “+/pizza” in EverQuest II, the second-most popular MMO at the time with 330,000 active users, players could place an order for delivery. The mostly young, tech savvy audience offers the ideal consumer profile that is willing to experiment with new products and hasn’t cemented their loyalty to brands yet.

For this tango, too, it takes two. In the past the relationship between game makers and advertisers has been strained. To illustrate, consider Microsoft’s 2006 acquisition of Massive, an in-game advertising platform. The initial promise was enticing: adding ads to blockbuster titles would allow creative firms to make more money per sold unit, and advertisers would finally be able to reach the growing audience for games. According to Massive’s CEO at the time:

“by aggregating the largest audience of gamers and providing real time delivery of advertising across top!selling video games, [it could] provide publishers and developers $1 - $2 profit per unit shipped.”

In the context of an increasing cost structure around the development and marketing of content, that was music to the ears of many senior-level execs.

The reason you probably don’t know about any of this is because it failed. It didn’t work because of at least two reasons: first, developers were by and large opposed to having advertisers chime in on their creative process. There was an obvious cultural rift between game makers and advertisers. It only exacerbated the fact that adding sponsored images generally late in the development cycle ran into practical issues. Having optimized memory allocation for a title meant it was cumbersome and largely impractical to enable dynamic content at the eleventh hour.

Second, audiences weren’t having it. Sure enough, everyone’s a gamer now. But back in 2006 it was the stereotypical hardcore gamers that were considered the lion’s share of the consumer base. Their response to the increase in the price for console games was predictable: The price of titles was going up, but consumers weren’t sharing in the benefit of adding ads. It felt like a trespass and an opportunistic strategy by game makers. Many quickly abandoned the programs with the exception of publishers like Electronic Arts, who established their own in-house ad divisions around their sports titles.

Nonetheless, in-game ads then were an afterthought in the same vein as we now see publishers “doing esports.” Unless it is part of the original blueprint, it goes nowhere.

That mentality is starting to shift.

Games’ love/hate relationship with ads

Seven years after King publicly broke up with its advertiser relationships to provide“an uninterrupted entertainment experience,” we’re about to see brands and their ilk roll into gaming in a big way.

Following its acquisition by Activision Blizzard, King changed its tune and went after what it called a $500 million opportunity. According to its most recent disclosure from 2020, earnings from advertising grew over +50% y/y. In 19Q4, ad revenue exceeded $150 million dollars. The Activision Blizzard mothership itself, too, has been accelerating efforts around advertising, which it regards as a way that enriches game play. According to its execs this “can even improve the concept of the game.”

Similar, Pokémon Go-maker Niantic has shown itself both willing and able to take ad dollars to fund its creative efforts. From its beginning the game maker embraced sponsorships. It ran a four-year long campaign with McDonalds in Japan, briefly brought life back to GameStop’s share price by making its stores PokéGyms, and continues to break new ground in mixing its augmented reality game with sponsorships.

And Tencent’s show pony, Riot Games, recently figured out how to add in-game banners but not the kind you’re thinking of. During broadcasts, players themselves won’t see the banners so there’s none of that anxiety around the integrity of the game. It makes sense for a game company whose two titles, League of Legends and Valorent, attract millions of viewers on Twitch daily. As its marquee franchise has matured, it can afford to explore a wider variety of income streams for its free-to-play triple A titles. Unlike 15 years ago, audiences today appear to be accepting of this novel commercialization.

An important explanation why ad dollars are especially alluring is the move of major publishers into free-to-play. Legacy publishers have long enjoyed pre-payment of their wares. For decades, you’d buy before you’d try. Hopping on the bandwagon as games became mainstream, CEOs like Bobby Kotick proudly announced how Activision Blizzard reached hundreds of millions of players. They managed to do so by making games free.

In a world where an enormous number of games are available for free there are only a few ways to build success. Micro-transactions have been the main source of income. However, as we’ve seen recently, publishers like Epic Games and Microsoft are moving toward recurrent revenue because (1) it absolves them from having to sell their audience each and every month to buy-in again, and (2) it fetches them a higher multiple for their share price.

Exploring ad revenue offers similar benefits. Here we find Unity taking the lead. Its recent IPO is predicated on providing a cheap engine to game makers that facilitates in-game ads as a primary monetization strategy. Its CEO, John Riccitiello, previously led EA when it was still in full product mode. Now, he’s got his targets set on ads.

The motivation is the same: it mitigates a reliance on singular income stream, and has higher potential upside if your audience proves to be particularly valuable to sponsors. That may work well for small fry outfits, but the real potential sits with the big dogs.

In its most recent earnings call, Zynga reported $616 million in bookings for 20Q4, which came with a new personal best of $117 million in ad revenue, up +47% y/y. That equates to 19% of total. Similarly, Glu Mobile, on the eve of its acquisition by Electronic Arts, reported $141 million in revenues, a +25% increase, which included 10% in ad revenue.

Top legacy firms like Activision Blizzard and EA are still learning, it seems, with $2.95 and $1.56 of income per mobile user, respectively. Especially EA made a wise choice to acquire Glu, because the mobile firm averaged a stellar $10.52 per mobile user, up +39% y/y, albeit over a smaller user base. Once the proposed merger is completed, EA’s average will increase to $2.66.

For all of these firms, adding advertising as a way to monetize the millions of non-paying players to their revenue mix will further mitigate the capital risk of development and the growing costs of user acquisition, which, in turn, will benefit market position and share price.

Watch Me Play

Gaming today isn’t just about playing anymore. A growing part of the addressable audience for game makers prefer also, or mostly, to watch other people play.

This isn’t new behavior. Rather than suffering through Silent Hill by myself, I instead courageously watched my roommate deliver the narrative’s punchline while I ate popcorn. It is no surprise then that live-streaming presents a more predictable avenue for advertisers.

Here Asia tends to lead. We can expect ad revenue here to grow in the new year. Already has titan giant Tencent future-proofed itself by facilitating the Huya/DouYu merger. Pre-merger, Tencent held a 36.8% stake with 50.9% of voting rights in Huya, and 38% of DouYu. Now with a combined 334 million monthly actives (mostly in China), Tencent will also integrate its Penguin esports brands, and have dominance over the category with a 67.5% voting share. Its two top-streamed titles, Honor of Kings and League of Legends, distribute (based on streaming hours) roughly as follows across platforms: 47% on DouYu, 41% on Huya, and 12% on Bilibili. It sets the stage for Tencent to now also control the marketing of content in the region.

In North American and European markets there is Amazon’s Twitch which, after a rough period, seems to have reached a whole new level of critical mass that undoubtedly will attract more ad dollars. In October, Twitch saw 1.8 billion hours of watched content, up +12% m/m, driven by (1) the buzz around the new console releases, (2) the start of fall and, of course, (3) the wild popularity of Among Us. Compared to the same month last year, Twitch viewership has doubled: 1.8 billion total hours watched in October 2020 compared to 900 million, up +97% y/y. And by the end of 2020 the numbers were even higher.

What makes live streaming especially powerful is its ability to gather audiences for a live feed. That can vary between on the high end from politicians like AOC discussing her latest concerns and questions about the GameStop short squeeze, which drew over 300,000 concurrents at its peak. Or it can be 2,000 people attending a dying friend’s last birthday. We are social creatures that like to connect. It may not immediately seem obvious to old-timey brand managers that continue to regard the games industry with suspicion, but the emotions we share online are incredibly powerful. Like watching your favorite team win, live streaming presents an undervalued opportunity to associate your brand with the rush of victory.

Fashion, Sports, Politics, and Music

I learned a lot in my time at Nielsen, especially as the point-person to explain to large well-known brands how video gaming would inevitably come to impact their business.

Predictably the conversation around leveraging games as part of a broader marketing effort generally emerges somewhere in the middle-management rank where a relatively young person looks to combine their favorite pastime with the needs of the company where they work. That is to, it is an uphill conversation. Senior management will generally ignore the advice, even as their traditional audiences age and shrink, because “that’s how we’ve always done things.” Anyone in charge of anything that says this is either stupid or afraid. In my experience mostly the latter. No one in the final years of their career is going to take a bet on something as suspicious as gaming.

Nevertheless, I’ve seen the attitudes slowly change. Ten years ago, even when confronted with extensive data that proved the ROI on game-related campaigns, old-timey ad execs turned it down. Today P&G holds an annual three-day gaming summit across all of its brands to formulate a plan. Evidently, dispute their insistence on data and measurable results, advertisers, like investors, suffer from FOMO.

Over the last few years brand holders have started to openly experiment with gaming as a way to reach new audiences. Increasingly, the argument goes, games need to be part of a brand’s toolkit in communicating with customers. Several industries have made some significant inroads.

Fashion. There is little difference between the impractical designs from high-end fashion houses and epic armor in games. It was only a matter of time then before cross-promotional efforts popped up: Prada collaborated with Square Enix for a fashion shoot to celebrate the 25th anniversary for Final Fantasy. So, too, does Gucci’s smartphone app feature arcade games. And Louis Vuitton dressed up marque characters from League of Legends, because, well, why the hell not? In-game skins are supposed to be hard to come by because that’s what distinguishes you from everyone else on the server. No one speaks the language of social aesthetic combined with individual expression better than the fashion industry.

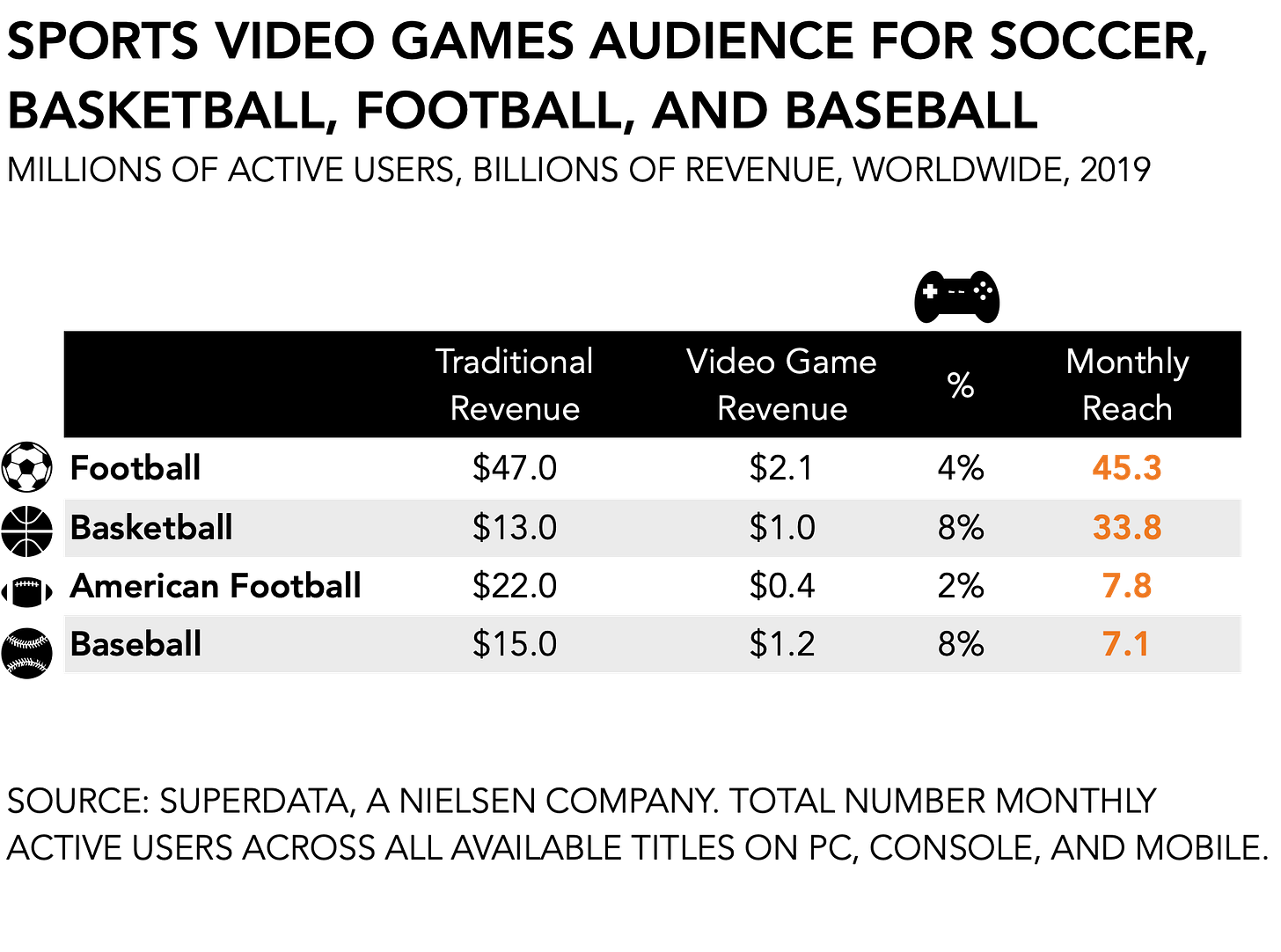

Sports. Sports video games have always been an odd combo of game play and advertising, especially since the category has come to rely heavily on connecting to the real world players, teams, and their standings. It offers a natural extension to keep existing fans engaged between real-world matches and reach new audiences that prefer to just play the games at home.

But outside the obvious franchises, the recent success and acquisition of Codemasters. Its F1 2020 launched a Virtual Grand Prix Series to replace postponed races that allowed regular mortals to compete against professional Formula 1 drivers and celebrities. Subsequently the game’s concurrent players in the first half of 2020 doubled compared to the previous all-time-high in 19H1. It was enough to convince EA to spend a 25% premium on the offer that Take-Two had made.

Politics. We’ve come a long way from America’s Army, a first-person shooter developed and published by the U.S. Army with the specific intent of informing, educating, and recruiting prospective soldiers. Funnily enough, the military always seems to be years ahead of civilian industries in exploring and exploiting new technologies. But that’s a separate topic. Most recently we’ve seen two clear examples of how government institutions and leaders are gravitating towards games to ‘get in touch with the voter.’ First, everyone’s favorite: The Biden/Harris campaign in Animal Crossing: New Horizons. In itself a massively successful title, it benefitted from a potent combo of novelty and the lockdown to drive awareness. And, second, watching congresswoman AOC debate current events during a two-hour live stream on Twitch reminds you that politicians today, as they have in the past, excel at finding the channels that reach their constituents.

Music. The example that needs the least explanation is music. A trio of in-game concerts made headlines over the past two years and has cemented the idea that people want to and will attend a live musical performance in their favorite online game. In short order: Marshmello, Travis Scott, and Lil Nas X saw 10.7 million, 45.8 million views, and 33 million aggregate views. Everyone is still a bit vague on the apples-to-apples here, but you get the idea: a lot.

(To give you an idea how early we still are in this stage, the article discussing Lil Nas X still misspells Fortnite because, apparently, no one in music plays video games. Anyway.)

The take-away here is that celebrity presence drives player participation. For Fortnite this meant, for instance, that Marshmello pulled an additional 2.4 million, or +29%, more viewers than the event in which a mysterious purple cube disappeared. It may not immediately be your cup of tea, but there is a strong affinity among players to witness simultaneous events together with others. And that is a language that advertisers and promoters speak very well.

Each of these examples are categories that spend a lot of money on advertising annually.

The apparel and accessory industry in the United States spent $22.9 billion on advertising in 2019, down -4% from $23.8 billion y/y.

The sporting and athletic goods industry in the United States spent $5.4 billion on advertising in 2019, up +13% from $4.8 billion y/y.

Political ad spend in 2020 reached $11 billion, of which $5.2 billion was dedicated to the US Presidential Campaign. Yes, election years show bigger numbers, but even then, that number was a +50% increase over the $6.5 billion total in 2016.

The music industry spent $5.8 billion in marketing and A&R in 2019.

The Road to Ads

The combined $40 billion in ad spend does not like a vacuum. A growing number of startups has emerged to connect the dots. Tel Aviv-based Anzu raised $9 million for a total of $14 million to expand its client base beyond Ubisoft, Lion Castle, Nacon, Pepsico, Samsung, American Eagle and Vodafone. As in-game ads are gaining momentum, the firm has grown from about 16 people in early 2019 to 50 today, based on LinkedIn data. Another example, Simulmedia, recently announced its partnership with EA to insert opt-in reward-based video ads into UFC 3. At roughly double the size of 102 employees, Simulmedia comes from the conventional TV ad space. The challenge for these firms is to convince game makers to collaborate.

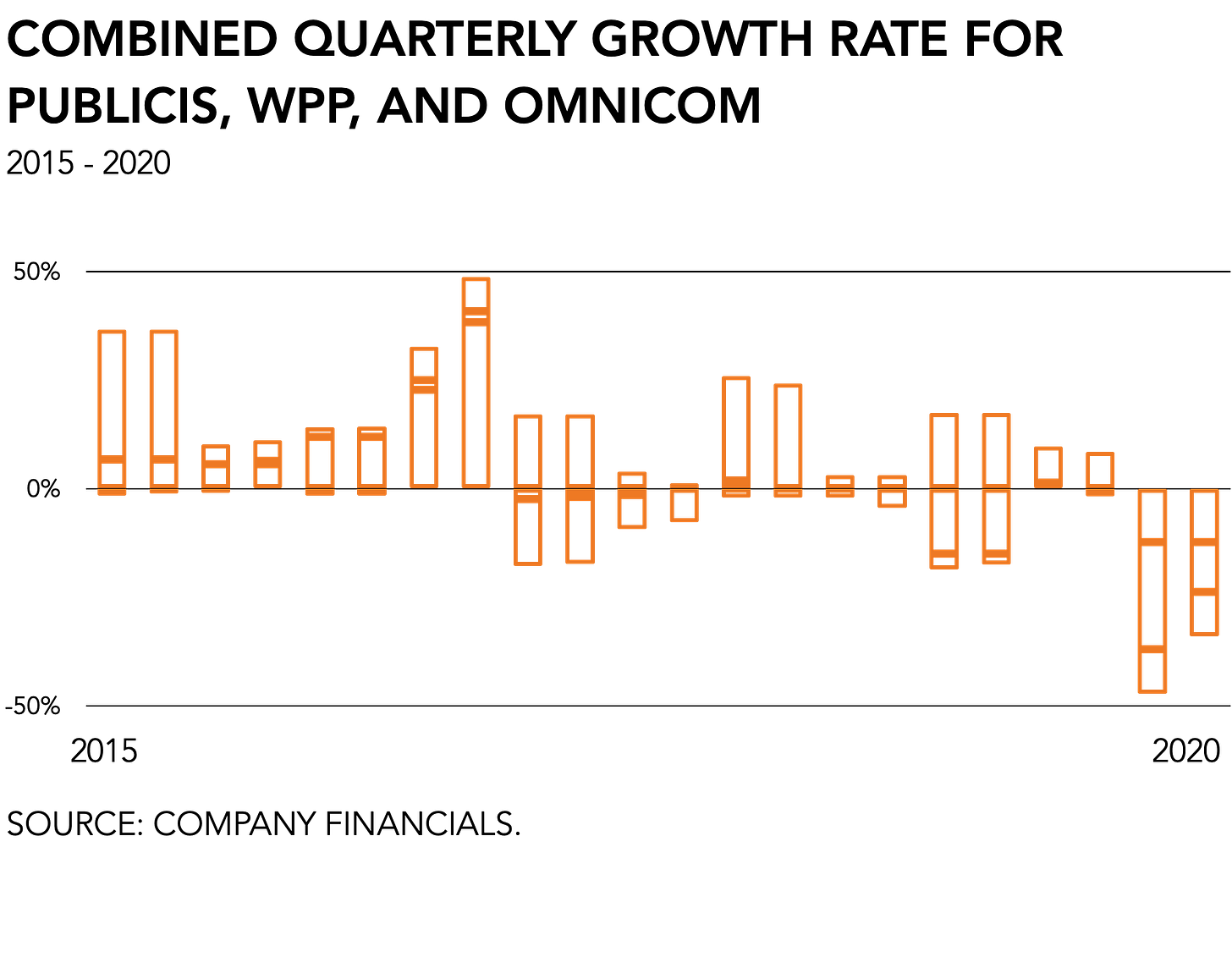

Previously, the biggest spenders would allocate 80% of their ad dollars early on. And, more importantly, few were keen to wager their job on some novelty. Advertisers are excited and projects are likely to get bolder. Ad agency Publicis recently launched a gaming group, stating

“gaming presents a growing variety of rich and interactive content formats that can improve message comprehension, recall and response, from the top to the bottom of the purchase funnel”

And according to WPP CEO, Mark Read, “Gaming is one activity that has exploded over the past year and increasingly an important advertising channel.” They’ll pretty much have to because their numbers have been terrible.

Needless to say, there is growing enthusiasm on both sides. But a few clouds remain on the horizon. For one, platform holders are still largely testing new ways to claim their own piece of all the anxious effort behind discovery. Apple’s looming roll-back of IDFA, which would make it more difficult and less accurate to target people, is an obvious ploy to claim some of that money for themselves. Team Cook plans to build a mini-Google on top of its App Store to charge companies for the honor of being the first search result. All for the sake of user privacy and protection, obviously. It also makes it more expensive to separate your title from the noise, which makes it harder to build an audience and, consequently, attract ad dollars.

By making people opt-in rather than opt-out of ads on their phones, the expectation is that 70% of consumers will be much harder to target. This will impact Facebook ability to make money, of course, and now the two firms are exchanging blows about who is right.

Next, there’s the issue as the parent of an 8-year old that terrifies me, because he already sees enough inappropriate, ill-targeted ads. And I’m sure I speak for parents everywhere when I say: fuck that. It was perhaps understandable in the context of conventional advertising when we didn’t know which 50% was effective, but it is entirely unacceptable that my kid sees ads that are well beyond his age.

The same goes for non-traditional audiences: ads may play a critical role in emerging markets and economies that have historically be largely outside the scope of game developers. But there’s always a risk that ads become a poor person’s tax. If advertisers seek to leverage novel technology without also safeguarding audiences and offering something of value, they will be doomed from the onset.

That brings us to a third challenge. There isn’t much in terms of measurement. An institution like Nielsen has long controlled the currency that advertisers and media used to do business. But today the research firm is still playing catchup. Sure enough, there are a bunch of small firms tracking live-streaming. But it remains a hard sell to big dollar companies to allocate their budgets based on the research pushed out by a 5-man crew.

We’ll be right back after these messages

The relationship between games and ads is warming up. As traditional categories fail to attract especially younger audiences, advertisers are exploring novel channels and content, which major game makers and live-streaming platforms are eager to supply.

Despite a decade of digitalization, game development remains fraught with risk and expenses, and using sponsors may be just the way to fund your creative vision. In aggregate, it also means that game development will change just like every other form of entertainment did.

And we’ll know that ads have fully arrived once Geoff Keighley opens a new category for the Game Awards like “Ad-Sponsored Game Development.” That’s okay. It is all part of becoming mainstream.