Before diving into the number circus that I’ve put together, I should warn you that, at long last, there is a podcast.

A colleague at NYU, Laine Nooney, and I have started recording our conversations for two reasons. First, with a few precious exceptions, most podcasts that cover video games and the industry around it lack depth. That’s okay. Have a good time. Enjoy.

But in a few short years, interactive entertainment has evolved from a fringe activity to the blueprint for the next internet. Since Laine and I each teach classes that explore the cultural and economic forces that shape video games, we figured we’d be well-positioned to go a bit deeper into what makes this industry tick. If nothing else, we have well over a hundred students between us that feed us interesting observations and commentary every week.

Second, there are a lot of people from other industries looking to learn more about video games. I personally have a ridiculous amount of inbound questions from people from other entertainment categories (e.g., music, film) and also fashion, sports, fast-food chains, telecom operators, and consumer packaged goods.

The pitch, finally, is that we’re exploring play and profit for the gaming curious, digging deep into why games matter in today’s economy. If you want to learn more about what makes the Steam Deck seem unusually popular, how come Chinese gaming titan Tencent is buying up Ubisoft one piece at a time, why European regulators are flexing to shut down the Microsoft/Activision Blizzard deal, or if you want wise up on the true origins of video games, you should check it out.

It’s available on Spotify, Apple, Google, and Substack, and we’d love to hear your thoughts!

On to this week’s update.

P.S. I’ll be in Amsterdam in the coming week. ❤️ 🇳🇱 🌷 If you’re there, let’s catch up!

BIG READ: Biggest buys in gaming for n00bs

In February this year, I did an analysis of how recent acquisitions would impact the games industry. At the time, I concluded that Microsoft’s proposed purchase of Activision Blizzard would not be detrimental to the distribution of market power and need not warrant intervention from regulators. The data I’ve collected since provides no reason for me to change my mind.

What is interesting, however, has been the panicked reactions to all this consolidation news.

The steady stream of announcements leaves the impression to many that something is awry. Game journalists already seem to agree that consolidation will be detrimental to everyone. Between Embracer buying up any studio not bolted to the floor, the biggest Chinese publishers buying up studios in France, and Sony shit-talking its rival Microsoft, much of the conversation around games industry consolidation remains poorly informed, however.

Certainly, the value and multiples of these transactions continue to increase. Super-charged consumer demand for interactive entertainment due to the pandemic, abundant cheap capital, and the entry of Big Tech has skyrocketed valuations.

Despite this boon, publishers are also increasing prices. A supply chain shortage has driven up the cost of equipment, a spike in demand has made capable developers more expensive, and the energy requirements and cost to host servers are going up. Square Enix is now asking $70 for Final Fantasy VII Remake Intergrade as does 2K for Tiny Tina’s Wonderland.

For premium titles that may be somewhat understandable. What’s odd is that free-to-play titles do the same. Tencent’s Riot Games, which recently raised its prices for its in-game currency, Riot Points, by 10 percent in the US and Europe, and CCP’s EVE Online increased its prices for the first time in almost twenty years by 10 to 33 percent, depending on the offering. And, finally, Activision Blizzard’s money maker, Candy Crush, also now gives you less for more, which did not go over well with some of its most loyal players.

Fifty-two billion dollar game makers

Even if the combination of industry consolidation and price increases sounds alarming, there’s more to it than that.

Digitalization and the popularization of the smartphone have vastly expanded the addressable audiences for interactive entertainment. It also made it much easier for a wider array of creative firms to publish their games. On PC, Steam, the biggest digital storefront, saw the release of well over 11,000 new titles in 2021 alone, up from a few hundred a decade ago. Mobile app stores similarly experienced a massive influx of new titles and users, as CEO Tim Cook recently disclosed that there at no fewer than 34 million registered developers in the Apple ecosystem.

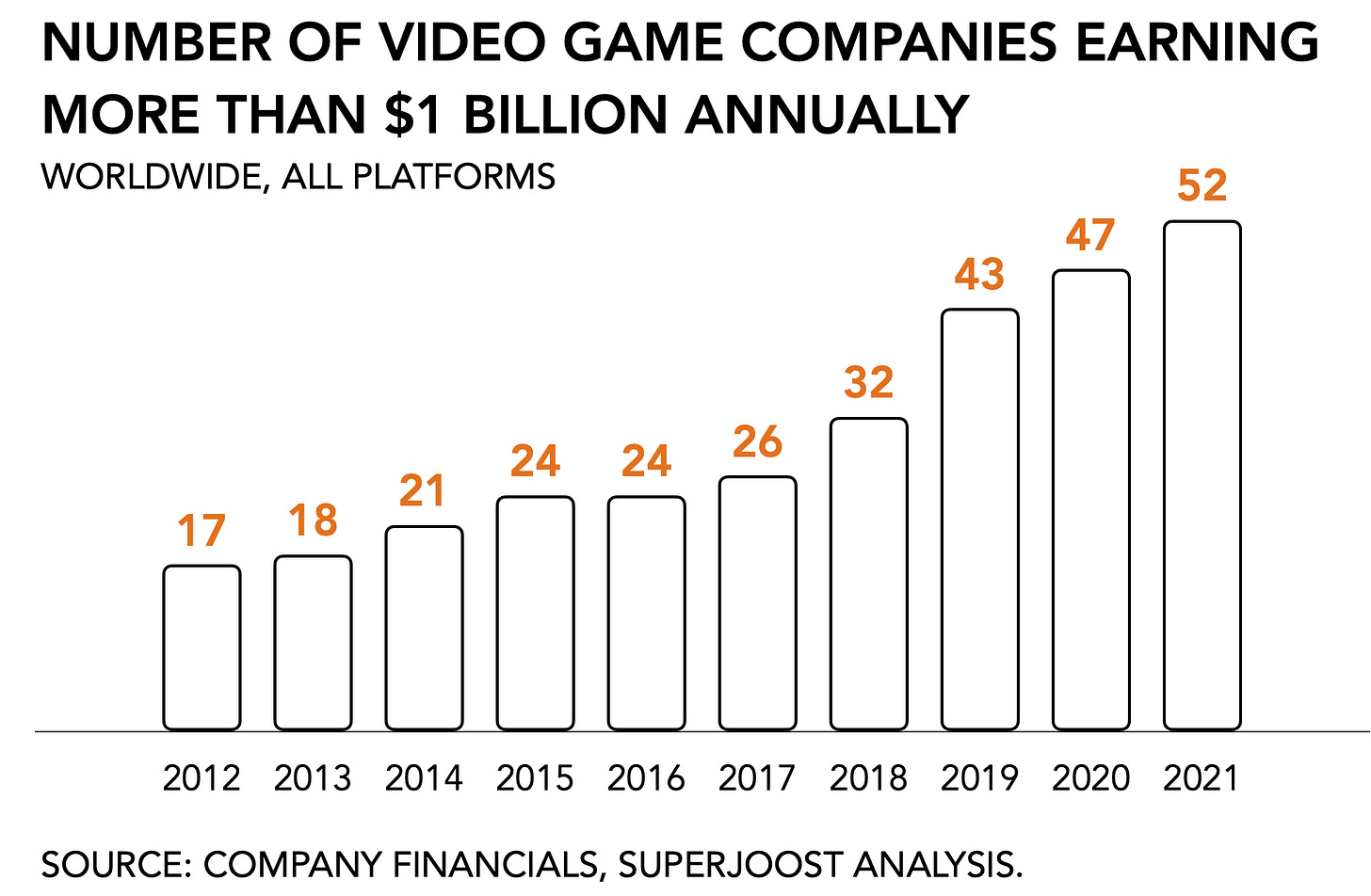

Such growth has resulted in more widespread financial success, too. Specifically, in 2012, there were seventeen game companies that generated over a billion dollars in annual revenue. By 2021, that number was 52. If we remove hardware manufacturers, the number drops to 46 firms making more than a billion dollars a year.

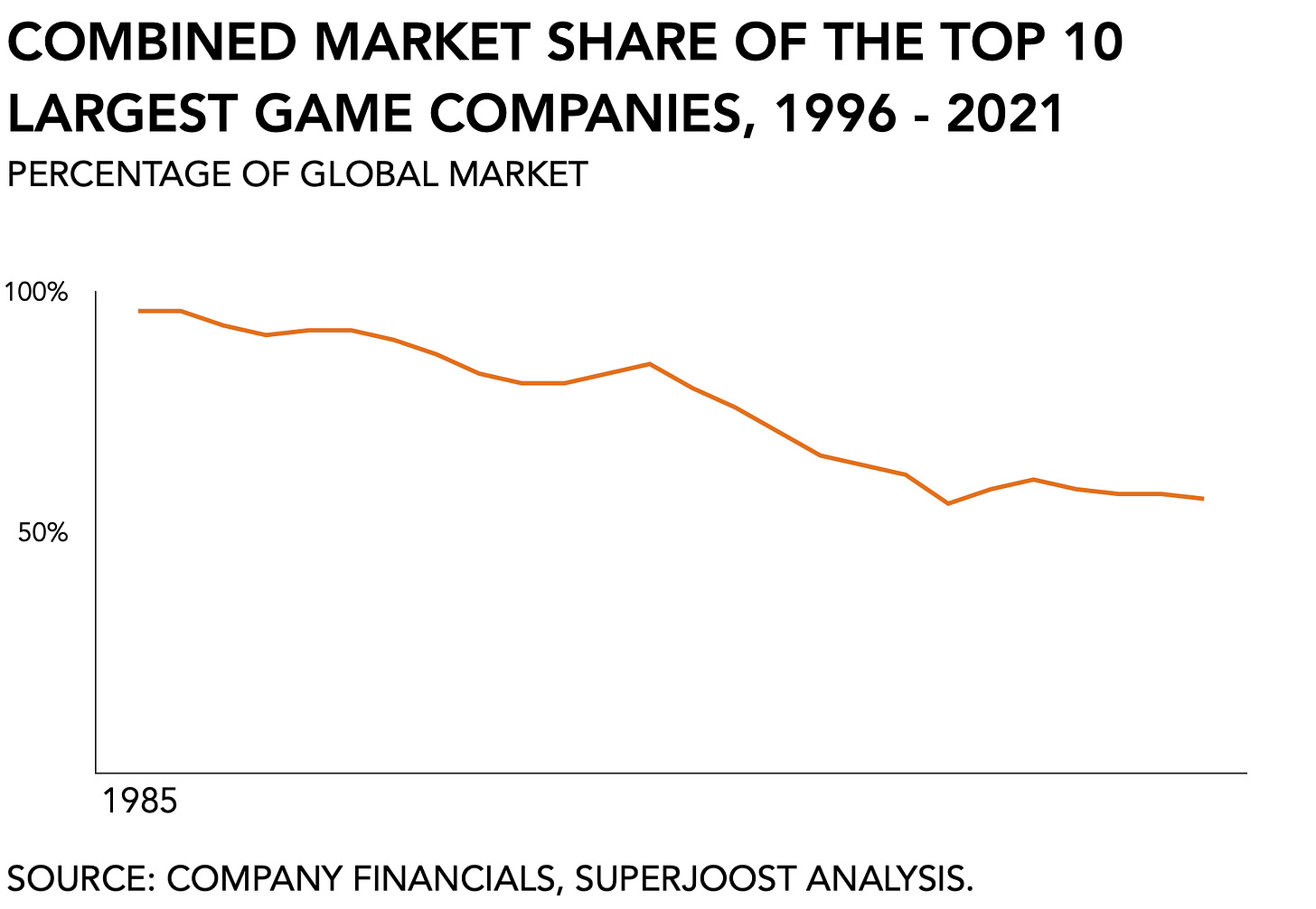

Yes, the largest firms have grown substantially, but so, too, has the overall competitive landscape. Even Embracer, for all its newsworthiness, only just recently broke the $1 billion annual revenue threshold. In the video games universe, it barely counts as a dwarf planet. The growth of the overall games industry negates the total market influence any single firm can wield. A boost in the popularity of video games softens the impact of any one firm becoming ‘too large.’

Platforms, not publishers, run the show

A second aspect to consider is that the market structure for video games today differs from before. In the pre-digital model when only Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft made consoles, successful game makers could count on favorable treatment from platform holders.

From its earnings reports, we know that Nintendo earns up to 85 percent from first-party software sales with the remainder accounted for by third-party content creators. The firm insists on maintaining profitability in all three of its hardware, software, and services divisions. As a consequence, the combination of stringent controls over quality and the vertical integration make Nintendo less attractive for publishers to release their games on its devices because they compete with a competitive content portfolio from the platform holder. It is why, for instance, Call of Duty isn’t available on the Switch.

By comparison, we find inverted ratios for Sony and Microsoft. For them, only between 15 to 20 percent of content revenue comes from their own (first-party) titles. Sony, a consumer electronics manufacturer, is heavily invested in the business of selling gaming consoles in combination with audio systems and high-end television sets. To entice consumers to buy its electronics it also invests in and acquires content. Sony is also one of the biggest owners in the world of music libraries and film production, in addition to the leading console manufacturer. And it has established strong distribution channels across major markets to get its various devices into the hands of consumers. From my own experience in dealing with Sony, the firm maintains intense scrutiny on inventory management, brand awareness, and pricing.

That dynamic between publishers and platforms is changing.

Over the course of a decade, platform holders have increased their share of total consumer spending by a factor of six, from $20 billion in 2012 to $118 billion in 2021. If we exclude the sale of hardware and dedicated gaming devices (e.g., smartphones, PC components, and consoles), platform holders managed to generate $118 billion in revenues from the sale of both their own (first-party) titles and those from third-party content providers. By comparison, game makers tripled their share, from $32 billion to $89 billion. That’s still a lot of growth, but it means that publishers’ ability to negotiate favorable treatment and margins has diminished. Over the course of a decade, platforms have increased their market share by 18 percent at the expense of publishers.

With a few exceptions, platform holders realized that owning intellectual property and vertically integrating content and distribution results in an increased market position. Epic Games, for instance, used the success of Fortnite, which generated $9 billion dollars in its first two years, to fund both the acquisition of content creators and establish a digital storefront, the Epic Game Store. It used the windfall to offer lower royalties to third parties than the incumbent, Valve, and woo publishers to release their content exclusively in its store.

It is possible that the power dynamic may swing back again in favor of the publishers. The popularity of online multiplayer gameplay, which especially young audiences favor over solo gameplay, combined with the push in crossplay (e.g., being able to play with anyone on any device) is giving content firms more leverage. It is why Sony relented to Epic Games and, finally, agreed to host Fortnite.

More broadly, in discussing the Microsoft/Activision Blizzard deal over the past months with publishers, it became clear that virtually no one opposes the deal, except Sony.

After first expressing concern about the proposed merger (in a Word document, mind you), Sony CEO Jim Ryan went a step further and issued a statement that argued it was “inadequate on many levels” for Microsoft to agree to continue the existing licensing arrangement for another three years. This claim comes from the dominant console maker, which also now charges $70 for Horizon Forbidden West, Ratchet & Clank: Rift Apart, and Returnal.

Sony has $400 million reasons to dislike the MSFT/ATVI deal. Here’s the quick math on it. According to page 8 in its most recent annual report, Activision Blizzard relies for about 15 percent of total sales of $8.8 billion on Sony, the third-largest after Apple and Google, which each account for 17 percent. That makes for about $1.32 billion. Assuming platform fees and other charges at around 30%, which is too high because Activision Blizzard is a big deal to Sony, the Japanese firm earns about $400 million from the arrangement annually. That’s the amount that will be at stake if the acquisition gets approval.

Creative firms, on the other hand, either reason that their dependence on console revenue isn’t very large or that an approved acquisition will benefit them as platform holders become more desperate for content. The reason for that is simple:

How gaming platforms make money has changed

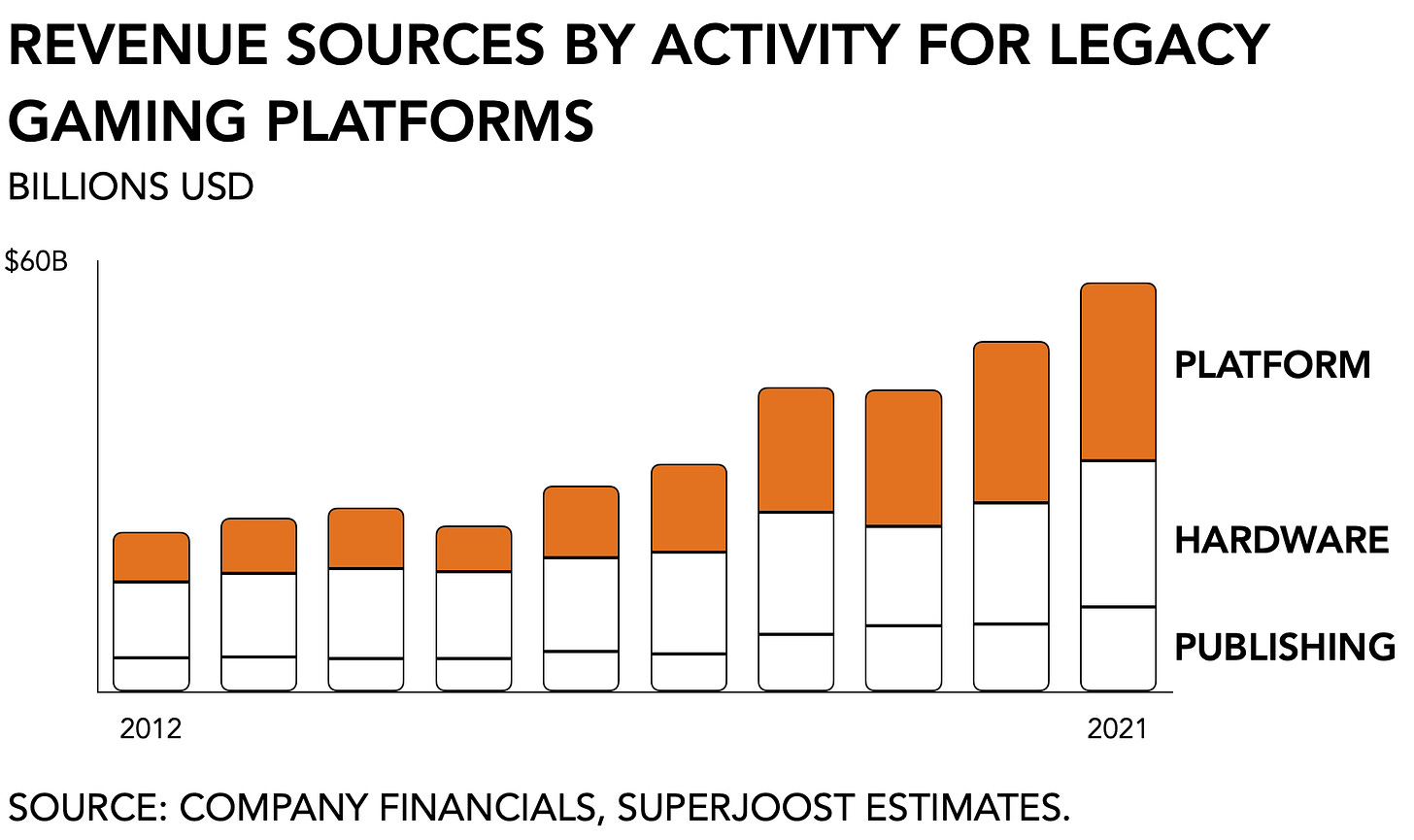

Between the legacy platforms—Microsoft, Nintendo, and Sony—there are three main activities that generate revenue. The first is hardware manufacturing. Each firm spends billions developing a proprietary device with an anticipated life-cycle of around every seven years.

Second, publishing their own games is an important part of establishing a userbase, because having attractive exclusive titles will encourage consumers to buy a specific device. Having more than one console is still only reserved for a minority of the user base.

Thirdly, each of these firms operates as platform holders that allow third-party content creators (e.g., publishers that they do not own) to release their games on their devices. Take-Two, for instance, releases Grand Theft Auto V on both the PlayStation and the Xbox. But Halo is exclusive to the latter, as is Horizon Zero Dawn to the former.

The ratio between the revenue generated from Publishing (first-party), Hardware (console sales), and Platform operations (third-party publishing) has started to shift over the past decade. Earnings from proprietary titles have stayed largely the same over the past decade at 21 percent. Hardware used to represent 47 percent of total earnings but has declined to 36% in 2021. And third-party publishing increased from 31% to 43% over the decade. Platform holders have switched roles and increasingly operate as an intermediary between game developers and players.

Add mobile platforms, such as Apple and Google, which don’t make dedicated gaming software, and newcomers like Big Tech, and suddenly everyone needs premium content to drive traffic, users, and subscribers. It is no wonder that Netflix struck a deal with Ubisoft last week, including its beloved Assassin’s Creed franchise, almost in the same breath that the French publisher sold another piece of itself to Tencent, and remains open for business with anyone else.

Let’s go wild

So let’s just say all of the major acquisitions that were proposed this year, including the ones that are just rumored, will get approved and happen. Will it meaningfully impact the market structure of the video games market?

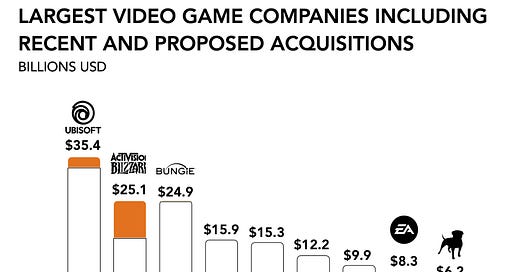

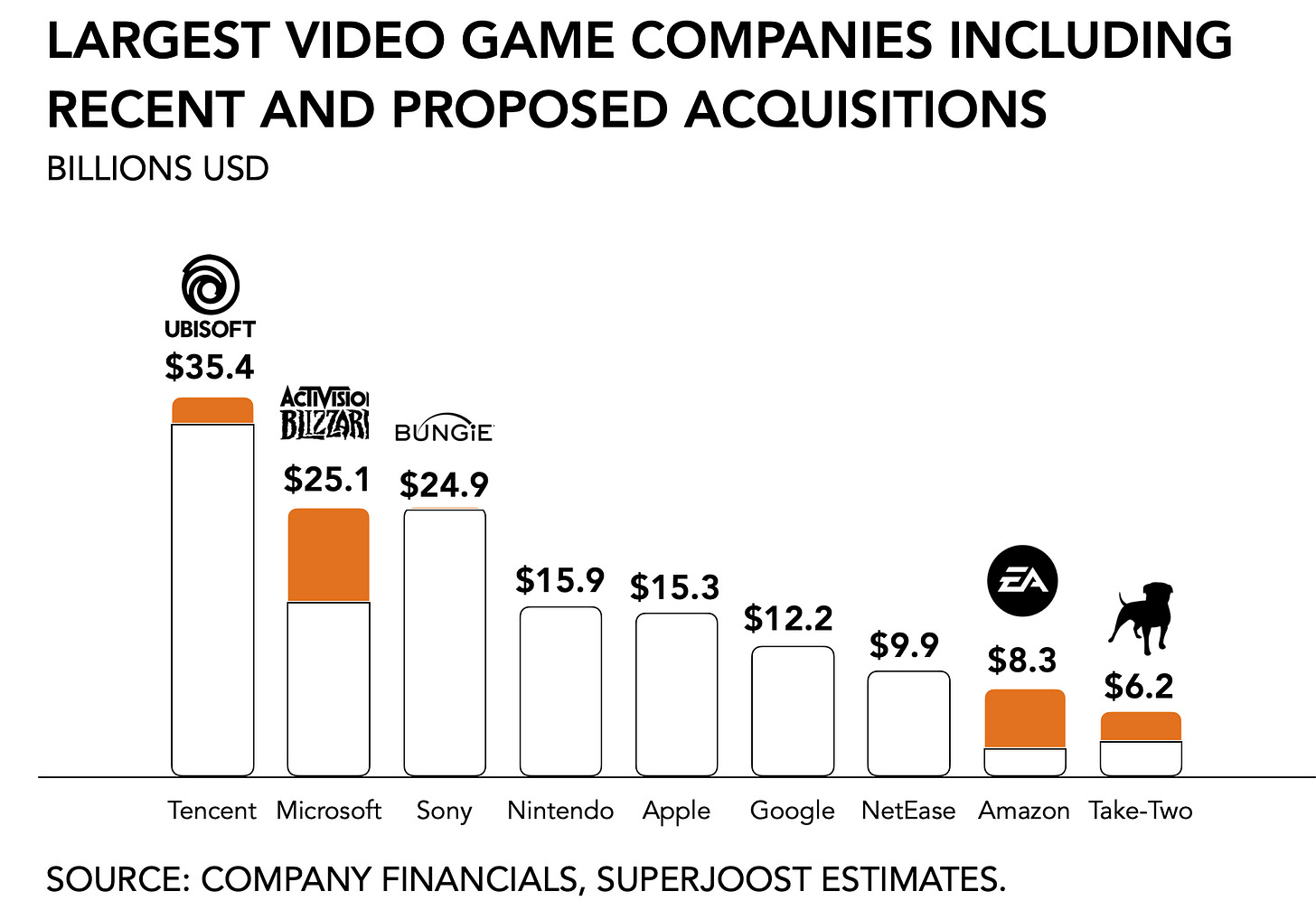

Adding Activision Blizzard’s $8.8 billion to Microsoft’s gaming revenue (hardware, first-party, and third-party) makes for a grand total of $25.1 billion. That’s just a few hundred million dollars more than rival Sony after its recently completed acquisition of Bungie, which is estimated to generate around $200 million annually. And don’t forget its $229 million purchase of Insomniac Studios, which gave Sony complete control over the Ratchet & Clank franchise and the licensing rights to Marvel’s Spider-Man. Finally, Take-Two bulked up after a string of smaller acquisitions and a $13 billion purchase as the grand finale. It brings its combined revenue to $6.2 billion.

Let’s add a few more just for kicks. For instance, there was the rumored acquisition of Electronic Arts by Amazon, which everyone denied, even though the former hired bankers back in May and the latter is going to need to get serious about its own content library because its own productions aren’t quite delivering on the vision. Hypothetically, between its earnings from Twitch, Luna, and its own titles, a purchase of EA would put Amazon at $8.3 billion.

And let’s also assume that Tencent stops dating Ubisoft and, finally, proposes (sorry, Laine). It would cost a paltry $4.4 billion, down from $12 billion from two years ago, and bring the Chinese publisher’s total revenue to $35 billion, giving it roughly a 15 percent share of the global games market.

Even with the inclusion of these deals that have already been killed or are highly unlikely to happen, overall market control remains relatively unconcentrated. Even under a ridiculous scenario, the share of the top 10 largest firms would only increase from 56 percent to 59 percent, or roughly where it was five years ago. It should be noted that 25 years ago the ten largest firms controlled almost 100% of the market, which has since then gradually declined to about half.

The popularisation of digitally distributed content and the smartphone, followed by the subsequent growth of the market, effectively negates much of the detrimental aspects of the consolidation of more traditional categories.

Oh, okay. So we shouldn’t worry about this?

As someone who’s been studying ownership trends in entertainment, media, and tech for the past two decades, it is a fascinating time. The steady stream of announcements of investments and acquisitions speaks to the vibrancy of interactive entertainment. Supercharged by the pandemic, the video games industry just experienced a growth spurt of historical proportions as abundant cheap capital and a spike in consumer demand drove gaming to new heights.

It is also very encouraging to see how much even average consumers and trade press care about the ownership structure of the video games industry. Increasingly seen as a precursor for the next iteration of the internet, the question of ‘who owns what?’ is critical in understanding whose interests will ultimately shape what the next version of online society will come to resemble.

As non-endemics, regulators, and a swath of new consumers wake up to the cultural relevance of interactive entertainment, its inner workings and market structure get more attention. Looking past the headlines is level one.

Great to see the podcast arriving, but the newsletter is still a must read...