Failing to regulate

What's next when the FTC loses this week

The SuperJoost Playlist is a weekly take on gaming, tech, and entertainment by business professor and author, Joost van Dreunen.

The first few days of deliberations proved rather disastrous for the Federal Trade Commission.

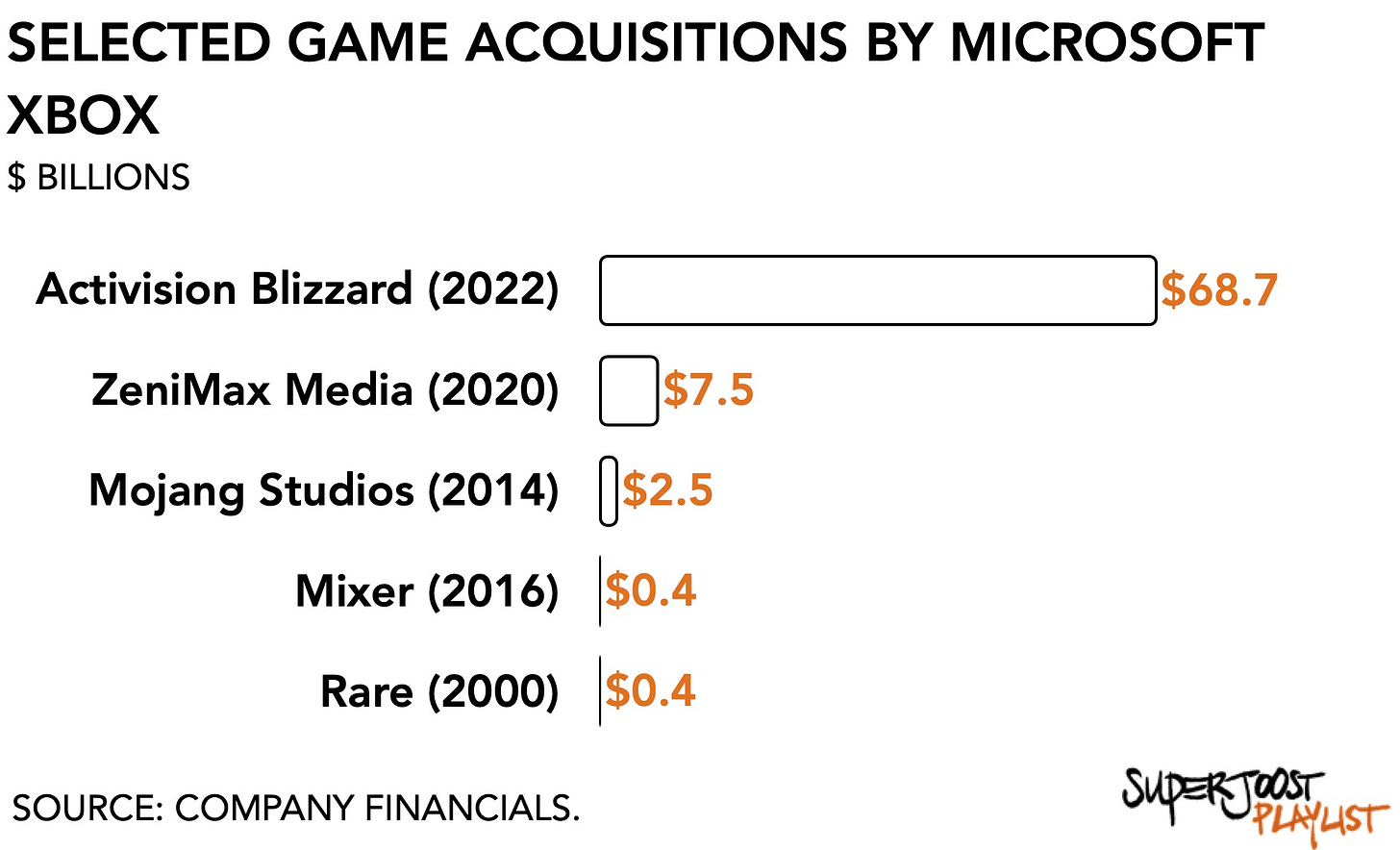

Its case against the proposed $69 billion acquisition of Activision Blizzard (ABK) by Microsoft is mired by a poor understanding of the games market by its litigators who so far failed to prove any theory of harm. Much of the FTC’s council displayed a poor understanding of basic industry fundamentals, like the difference between first- and third-party publishing. Quizzing Microsoft on acquisition basics, predictably, backfired.

FTC: "Now you have a $70 billion upfront payment that you're making for Activision, right?"

Phil Spencer: "No, when you acquire something it's not a payment. It's like when you buy a house. You're buying an asset that has value so it's really a transfer of cash into an asset called Activision, that you believe retains the value that you acquired. So to try and characterize the $70 billion as somehow spent is incorrect. Financially, it's really moving $70 billion in cash into an asset, which is a game publisher, that to us is actually worth more than $70 billion, so it is not spent."

Further weakening the FTC’s case, evidence emerged that PlayStation CEO, Jim Ryan, didn’t really think the merger would negatively impact Microsoft’s rival. Despite all the fanfare and abundant use of the corporate jet to advocate its interests as the largest console maker to regulators, Ryan wasn’t really worried at all. In an email from last January, he wrote that the PlayStation business will be “more than okay.” That’s exactly how you’d expect an apex predator to behave: crying foul to gain an advantage. And adding insult to injury, the judge intervened in the FTC’s cross-examinations, as its lawyers seemed to lose focus in their questioning. It makes an overall weak impression.

[The play-by-play details of the case are readily available, but, ICYMI, I recommend you read up on things via Stephen Totilo and Florian Mueller.]

What winning means for Microsoft

I’ve argued repeatedly that the deal will go through as planned despite initial opposition, and that it would be a pro-competitive move. After last week’s proceedings, the chances of the FTC winning the case are approaching zero and the most likely outcome is Judge Corley siding with Microsoft. I fully expect Microsoft to be cleared to proceed, even if its victory will undoubtedly remain controversial for some time to come. Approval in the US will put pressure on the appeal that is currently underway in the UK following a block of the merger by the Competition & Markets Authority there. With a win in hand at home, overcoming the block overseas starts to look like a formality.

My focus here goes to what’s next.

With this much momentum, goodwill among gamers, and its main rival Sony unable to stop incriminating itself, all eyes should now be on Microsoft’s next move. You’ve won the case and the popular vote. Now make it count.

Immediate evidence from this week is promising. Sarah Bond’s testimony was convincing and above reproach. Her ability to calmly and concisely answer questions displayed her maturity as a leader and sincerity in delivering novel experiences. Similarly, Phil Spencer displayed the steady hand, candor, and stamina you’d expect from someone in charge. I’ve met these people, shared a meal with them, and have been able to see them among peers. Both of them have engaged with me on analyses I presented to them. They are smart, detail-oriented, well-informed, and not afraid of confrontation.

But Microsoft does have a history. Its $10 billion acquisition of Nokia to establish its own mobile division went nowhere. The effort to compete with Twitch and YouTube by buying Beam (and renaming it to Mixer) resulted in nothing. Skeptics of the deal have expressed Microsoft’s changing stance on what titles will be exclusive post-merger in the wake of the ZeniMax Media acquisition. And the recent release of Redfall left a lot to be desired. Arguably the only acquisition in Xbox’s history that speaks to an optimistic read of what’s next is its purchase of Minecraft.

Team Xbox is arriving at a critical junction. Its GamePass service is growing nicely, we’re told, and leadership has increased the release cadence. Upcoming titles like Starfield are expected to grow the player base across devices and platforms, allowing it to evolve itself and gaming more generally. As it reaches the endzone in its case against FTC, Microsoft must make good on the promises it made along the way.

Testing new rules

Losing its lawsuit against Microsoft does not mean that the FTC’s instincts are wrong, however.

Much of the current pushback by antitrust watchdogs originates in the ruthless tactics among large tech firms, ranging from absenteeism to outright exploitation. These companies are so large that they jeopardize the usefulness of indexes like the S&P500. A handful of firms have grown to a size that exists outside of the reach of governmental enforcement while endangering anything from individual privacy rights to environmental impact for their chipsets and batteries. Or, as Vili Lehdonvirta, a professor at Oxford University puts it: “digital platforms have become the new virtual states” and regulating them properly is a different order of magnitude.

Indeed, there is a fair case to be made that the same regulatory policy meant to curb anticompetitive behavior among large industrial conglomerates seeking to consolidate power by establishing economies of scale cannot be applied to Big Tech. These platform companies rely on different economics, in particular by subsidizing one type of activity (e.g., streaming video) by reaping disproportionate profits elsewhere (e.g., e-commerce).

Next, there exists a documented history of mergers failing to deliver or even keep their promised benefits. When AT&T announced its plan to acquire entertainment company Time Warner in 2016 for a total of $85 billion, the US Department of Justice sued to block the merger. After a six-week trial, the judge ultimately sided with AT&T and allowed the deal to go through.

But the AT&T/Time Warner merger, we now know, turned out to be a dumpster fire. For starters, AT&T’s CEO, Randall Stephenson, had argued during the lawsuit that raising prices post-merger would be absurd, and stated that doing so “literally defies logic.” Sure enough, he did so anyway by increasing the cost to consumers for its DirecTV services and terminating its $15/month trial offering for pay TV.

Next, AT&T argued that as a result of the merger, it would be able to create more jobs and add workers. It did not and, instead, laid off 41,000 despite receiving a $42 billion tax cut. It literally cut a host of long-time employees during the pandemic.

Another is the argument that an emboldened AT&T would be able to compete more effectively against Google and Facebook by consolidating its entertainment division and bolstering its ad tech capabilities also proved false. Why would advertisers pay for ad placements when it would rival the prominence of AT&T’s own internal media and entertainment businesses?

I’ve made a similar argument in the ABK/MSFT deal. I argued that especially ABK’s mobile franchises (e.g., Candy Crush, Call of Duty Mobile) would afford Microsoft a more prominent position in the mobile ecosystem, which is currently a duopoly governed by Apple and Google. I have more thoughts on this, of course, but off the cuff, the comparison between AT&T and Microsoft is apples to oranges. The latter already competes in the console and PC markets, but not yet in mobile. Access to this new market has the potential to redistribute the power structure between them by extending Microsoft’s existing publishing activities. AT&T, on the other hand, sought to infringe on the ad business which was an entirely new category for them at the time. Based on AT&T’s behavior before and after the Time Warner deal, the FTC’s skepticism of large acquisitive conglomerates is well-founded.

And, finally, Wall Street loves mergers because of the short-term gains. At its current price of $82 a share, Microsoft’s offer to buy ABK at $95 a share makes for a nice payout for existing shareholders. Good for them. But there is evidence that acquisitions erode shareholder value and wages alike. For example, a long-term analysis of 268,350 M&A transactions over a 20-year period found that

“corporate acquirers in the US generally tended to underperform the market. And the bigger the deal, the worse the returns.”

That puts the ABK/MSFT merger in a different light. Similarly, employer concentration tends to negatively impact wages. According to a study covering the period between 1977 to 2009 from the Kellogg School of Management,

“consistent with labor market monopsony power, there is a negative relation between local-level employer concentration and wages that is more pronounced at high levels of concentration.”

It suggests that the current lawsuit, while heavily criticized across the aisle and among investors, has merit in managing both the domestic and global economy with a longer time horizon.

What losing means for the FTC

One explanation for why the FTC is having such a tough time in and outside the court is its wholesale shift in management. Its chair, Lina Kahn was one of Biden’s appointees and part of a push to reform regulatory policy. I’m personally a fan of her writing, which is timely and more in tune with the challenges around a platform economy in which ‘winners take most.’ But I’m not surprised that a Democratic woman of color would face criticism and scrutiny from Republicans and bankers.

What the FTC needs is a resounding win. But the watchdog faces opposition to rewrite regulatory policy from different angles. Internally, the sole Republican commissioner, Christine Wilson, resigned in February. In her remarks issued in April 2022, she accused the FTC’s new leadership of taking a binary perspective as, according to Wilson, Kahn and comrades believe “[o]ne is either a pro-monopolist or an anti-monopolist, period.” And, big means bad.

Unfortunately, the US government doesn’t have a strong track record preventing vertical merger cases. Certainly, there was the DoJ’s victory last year when the court blocked the $2.2 billion takeover of Simon & Schuster by Penguin Random House. And the FTC sued to block Lockheed Martin's $4.4 billion proposed acquisition of Aerojet. In both cases, the involved parties abandoned their respective mergers. To bolster its efficacy to regulate large, platform-based markets where vertical acquisitions are more prominent, the FTC and the Department of Justice issued new guidelines in early 2022.

Central to the current FTC’s thinking is the notion that markets are not naturally occurring phenomena, but (as we also learned from Phil Spencer about the console wars) a social construct and, therefore, political. Kahn has repeatedly and openly argued that existing competition policy is written by defenders of the status quo. Many of her colleagues and mentors regard existing competition policy and the economic language used to describe it as a tool wielded by the elites.

That’s an important and reasonable point to make. The field of economics at large lacks diversity. More so, leading economic policymakers are becoming aware of the inherent tension between personal politics and objective methodology. According to Diane Coyle, a former advisor to the UK Treasury and member of the UK Competition Commission from 2001 until 2019,

“values cannot be wholly separable from empirical investigation, and yet it is important for economists to aspire to be as impartial as possible.”

Economic policy, at its core, is a tool for elites. As I’ve argued, the obfuscating practices observed in the CMA’s evaluation of the ABK/MSFT deal prevent a broader dialogue and steer toward an unnecessarily drawn-out process.

As such, the FTC has severed a lot of ties and abdicated existing practices. Kahn prevented staff from attending conferences, for instance, on the basis that it would only accommodate those already in power. In fact, Kahn’s former right-hand, Tim Wu, has been quite vocal about “the incredible secrecy and technical nature” of the merger review process. And Rohit Chopra, former FTC Commissioner and current Director of the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau, observed that

“[g]overnment officials were often seen as auditioning for a future job in finance to exploit their inside knowledge to help dominant financial firms extract special favors and evade accountability for wrongdoing.”

A radical break with how things are done may be an obvious method to achieve a different regulatory outcome. However, losing to Microsoft weighs on the FTC’s ambitious agenda. Already the outfit has managed to lose a string of cases. And its unwillingness to work closely with others prevents it from accomplishing more. Perhaps softening its stance will allow the US watchdog to be more effective. The FTC’s sweeping policy changes since the appointment of Kahn now face a credibility test that will be measured in the successful outcomes in antitrust enforcement, especially around high-profile cases like ABK/MSFT.

Having a strong, convincing win on the books (read: preventing the ABK/MSFT deal) would validate that effort. But given the past week’s courtroom drama, that’s not going to happen.

Even so, there are some aspects that are positive indeed that we may attribute to the regulator. Along the way in its ABK/MSFT journey, Microsoft did manage to get a few things right. In recognizing collective bargaining rights, the firm has taken a different path than many of its tech peers. The same Kellogg study that found a negative impact on wages as a result of employer consolidation also determined that an absence of unions exacerbates the effect. It concluded that

“the negative relation between labor market concentration and wages is stronger when unionization rates are low.”

It seems therefore promising that Microsoft has made nice with the Communications Workers of America. I’ll leave it to speculation whether that was already in the works or if, in fact, the FTC’s pressure accelerated that process, thereby making it a clear win for the government agency and evidence of its efficacy. But it would directly speak to the criticism voiced by the current FTC school of thought which worries about the impact on labor and competition.

The FTC’s upcoming loss this week may provide a chance for what the games industry knows as a post-mortem, and review how it may iterate to better regulate one of the most pressing issues of our time.

I strongly agree that Microsoft is winning in the federal district court proceedings, and that the likely outome is that the federal district court will deny the preliminary injunctive relief requested by the FTC.

But, I think both sides legal counsel are doing competent work. Unfortunately for the FTC, the US antitrust law regarding vertical mergers would have to be radically changed in order for the FTC to prevail. My assessment is based on my review of the current case and the US antitrust case law, as well as general legal knowledge gained in my career as a litigation attorney in hundreds of complex major cases, including two merit wins at the Supreme Court of the United States.

I think the claim that the FTC losing will put pressure on the CMA appeal process misunderstands what the remit of the CAT is. That said, I think an interesting dynamic may come if Microsoft decides to pursue the acquisition in defiance of the CMA, but at the moment I think that's more bluster than anything else.