Layoffs by design

How company ownership drives layoffs in the video game industry

The SuperJoost Playlist is a weekly take on gaming, tech, and entertainment by business professor and author Joost van Dreunen.

As Roblox continues to expand in its reach and relevance, two things are happening.

The first is, of course, that we are witnessing the emergence of a novel channel that facilitates some innovative new forms of play. If you haven’t already, you should check out Grow a Garden. These breakout successes are generating their own subset of teenage millionaires, which is cultivating a new generation of digital creatives.

Roblox’s immediate response to these homebrew successes has been to publicize them, of course, as indicators of cultural relevance and creative activity. Its positioning as a digital playground is starting to manifest and, from the looks of it, quite lucratively so.

Second, Roblox will likely encounter growing pushback. Such is the nature of success. I provided some feedback and comments to this week’s write-up on After Babel, the substack started by my NYU colleague, Jonathan Haidt. I’ve previously reviewed his book, The Anxious Generation, and was happy to help guide the conversation in a more equitable direction. It’s well worth the read.

The same platform that empowers new forms of play also invites new forms of pressure. Even digitally, you reap what you sow.

On to this week’s update.

BIG READ: Layoffs by design

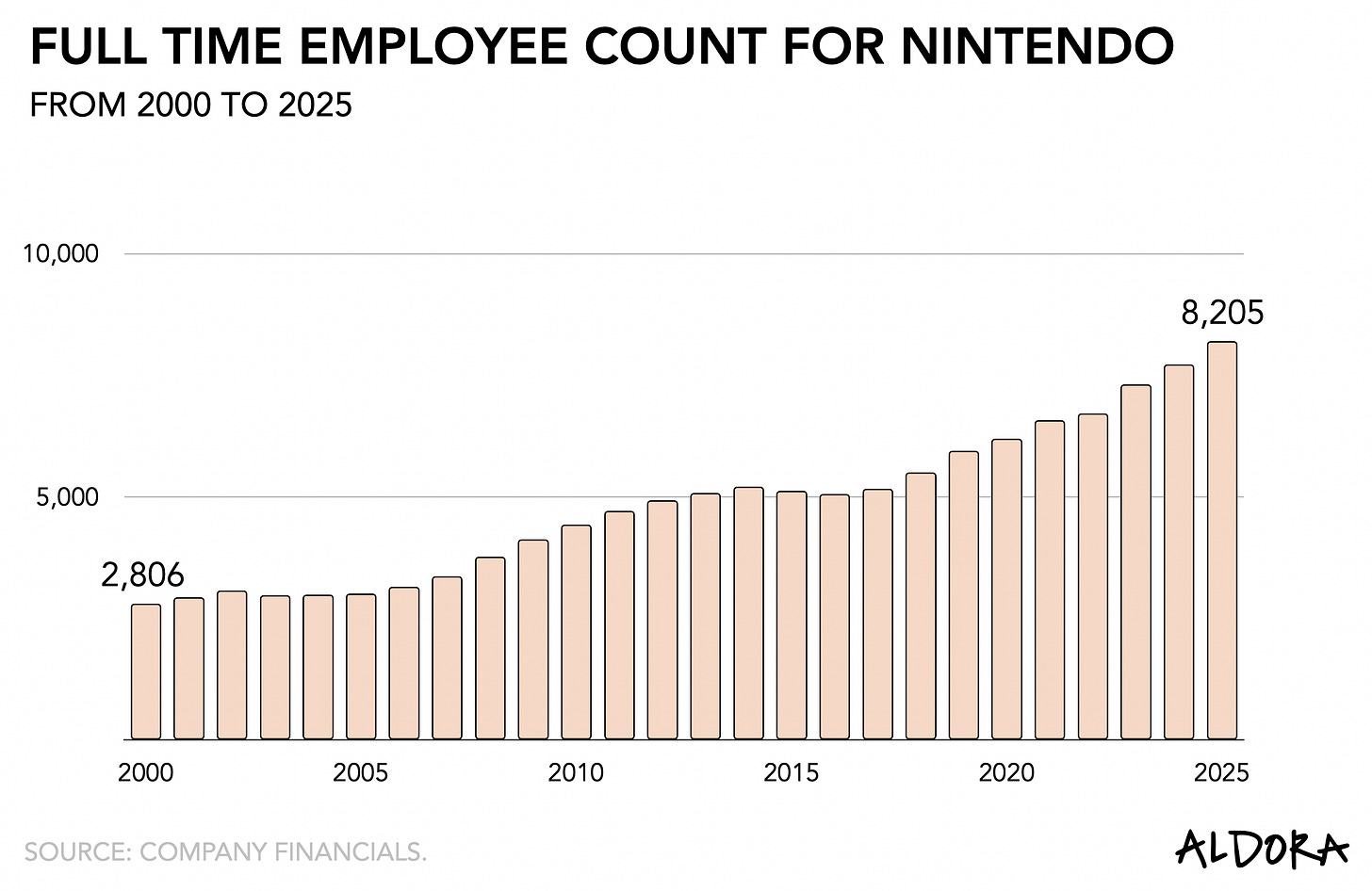

In yet another year defined by job losses, Nintendo is hiring.

According to its latest financial filing, the Kyoto-based company grew its staff size by 6%—from 7,724 to 8,205—reaching an all-time high. Even more notable is its attrition rate, which remains under 2%. At a time when “efficiency” is the industry’s favorite euphemism for cost-cutting, Nintendo’s growth seems almost contrarian.

But it is not alone.

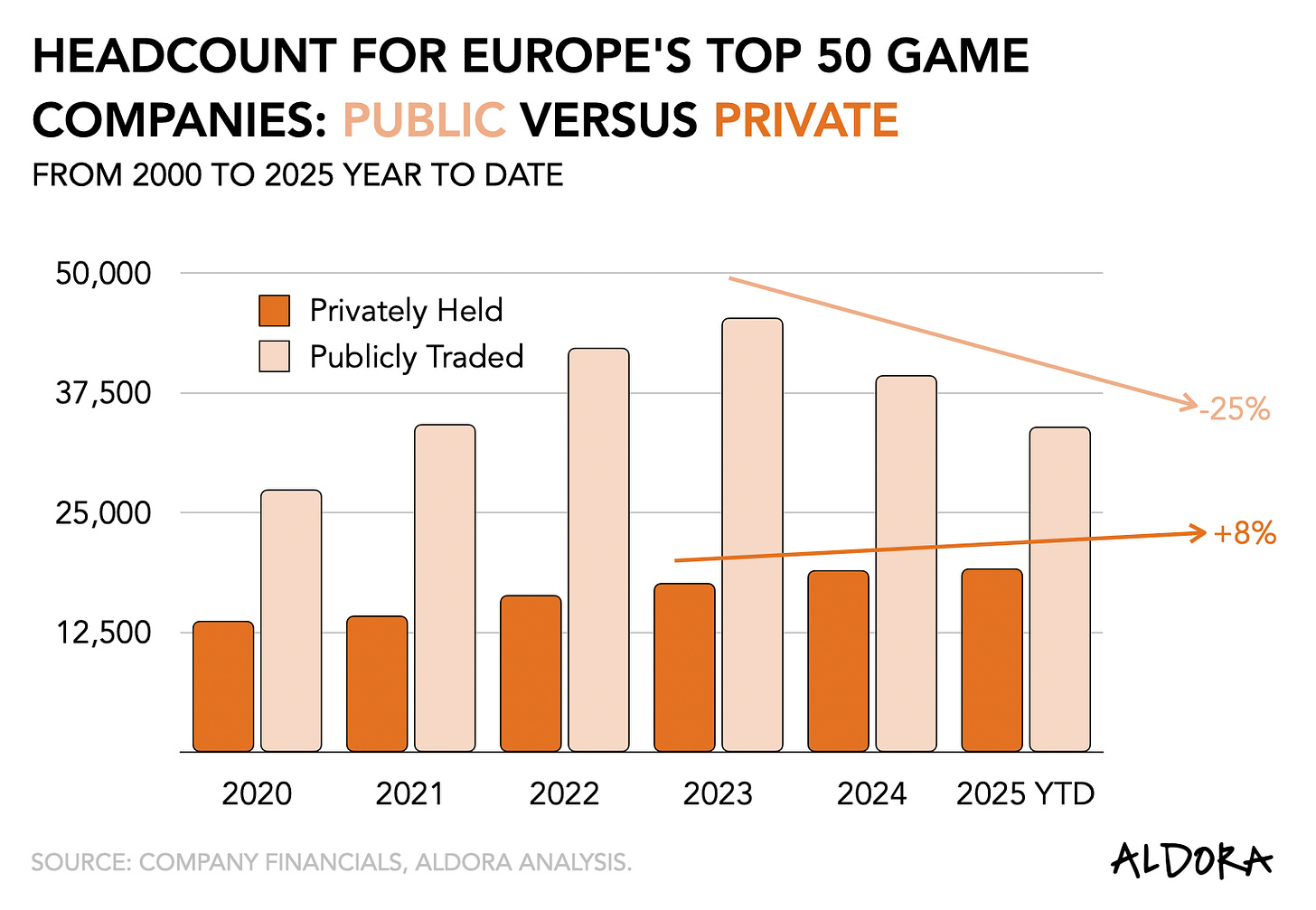

The shift is not industry-wide. While public firms are contracting, in Europe, privately held studios are bucking the trend.

What follows is the final installment of a three-part analysis of the industry’s ongoing labor reset.

In Part One, “No Kings Left in Gaming," I demonstrated how the top of the market—Sony, Microsoft, and Electronic Arts—can no longer escape gravity. The post-pandemic contraction is finally catching up with the largest firms. Despite outsized revenues, they’re shedding staff, shuttering studios, and walking back overextended bets. The premise that scale and IP depth serve as moats no longer holds.

In Part Two, “Firing on All Cylinders,” I examined how even well-performing units like King and ZeniMax weren’t spared. Xbox’s layoffs signaled a broader shift from expansion to efficiency. A 19% surge in headcount since 2012 had to be scaled back. Performance marketing no longer guarantees growth. Without a coherent ecosystem strategy, even market leaders are vulnerable.

This week, we zoom in on a corner of the industry that defies the trend: Europe’s privately held game studios.

The following analysis draws on a comparative assessment of the fifty largest game makers headquartered in Europe, tracking employment from 2020 through the first half of 2025.

Public versus Private: Diverging Labor Models

Over the past few years, a quiet but revealing divergence has emerged.

While public game companies across North America and Europe have aggressively trimmed staff—collectively reducing headcount by an estimated 9% year-over-year—Europe’s privately held studios have moved in the opposite direction. Firms like Dream Games, and Moon Active, and Huuuge Games have not just stabilized but expanded. Dream Games exemplifies this trend, growing from 219 to 364 employees—a 67% increase in just two years, while competitors shed thousands.

This isn’t merely anecdotal. A side-by-side analysis of employment trends among the fifty largest game makers in Europe reveals a clear distinction: public firms are shrinking, while private firms are growing. Since 2023, European public firms have reduced their workforce by approximately 25%. Unlisted game makers, by contrast, have increased theirs by 8%.

One explanation is that public companies operate under quarterly pressures that their counterparts don't face. When revenues dip, public companies reach for the most visible lever: headcount. It's quick, it's measurable, and Wall Street understands it.

By contrast, non-public companies can weather the same storms by shifting resources, pausing projects, or simply accepting lower margins for a quarter or two. Rebellion CEO Jason Kingsley, whose studio has avoided layoffs during the industry downturn, explained their approach:

"I think we control our budgets quite carefully. We have substantial budgets, in terms of millions and millions of pounds, but we don't have hundreds of millions of pounds. We try to make it that we can make a really good game, and it has a very decent chance of making a profit."

As a result, these developers have steadily expanded since the industry began its decline.

That doesn’t mean all of them have avoided layoffs. Crytek, for example, saw an 8 percent reduction in its workforce over the past two years. However, these companies make such decisions with different motivations than their publicly traded counterparts.

The key takeaway is structural: the ownership model shapes labor strategy. Public companies act like financial instruments, streamlining operations to meet liquidity and investor expectations. In contrast, private firms operate like product companies, prioritizing creative control and longevity. This distinction is evident in workforce decisions, where public firms reduce staff to meet margin targets, while their independently held counterparts prioritize retaining talent and recalibrating development roadmaps.

Public firms externalize risk onto workers, communities, and innovation itself. Rather than disappear, the cost of layoffs is merely displaced, often to public institutions and creative ecosystems that must absorb the fallout.

It also maps to a broader tension in platform economics: markets demand predictability, while games reward experimentation. This mismatch has become embedded in the system.

The irony is that those best positioned to take creative risks—significant, well-capitalized public companies—are the least likely to do so. Instead, the riskiest innovations are outsourced to smaller studios with fewer resources and higher stakes.

What we’re witnessing is not a European anomaly or a mobile-specific trend. It’s a reorganization of the industry, a strategic realignment where risk is pushed to private firms while publicly traded companies de-risk. The implications are clear.

Expect continued divergence, marked by increased private hiring, further consolidation among undercapitalized studios, and ongoing pressure on public incumbents to deliver growth under tighter constraints.

Combining all three pieces of the analysis, a single theme emerges. The current layoffs are part of a strategic reckoning. The industry’s top-heavy incumbents, fattened by years of expansion, are now cutting muscle under the guise of discipline. In public markets, even strong performers like King and ZeniMax get cut as their results become less predictable. Europe’s private studios, along with Nintendo’s counter-cyclical steadiness, show that an alternative path exists: one where headcount is an asset, not a liability. It gives us a sense of what’s ahead.

In this context, Nintendo’s counter-cyclical discipline looks less like a quirk and more like a blueprint. Like its supply chain, it closely controls its staff size, makes focused bets, and thinks long-term, even when this goes against short-term financial logic. It reflects an alternative model of efficiency: one in which productive capacity rather than margin optimization is the central objective.

More than a matter of economic prudence, Nintendo’s steady growth is a deliberate strategy rooted in its productive capacity. The objective measure of efficiency is not how quickly a company can cut costs, but how well it preserves capacity for long-term value creation.

That approach does not dominate headlines. But it will likely define the next phase in interactive entertainment.

NEWS

Netflix’s foray into gaming continues to evolve

Even amid internal restructuring, Netflix is not giving up. In its second-quarter earnings call, Co-CEO Ted Sarandos framed games not as standalone products but as integral components of Netflix’s broader entertainment ecosystem. As with film and television, the objective is not to chase isolated hits, but to maintain a consistent cadence of content that strengthens subscriber engagement.

In practice, this means leveraging gaming to extend the life cycle of key IP—such as Wednesday or Squid Game—without introducing friction through direct monetization. Games are positioned not as revenue generators but as retention tools, integrated into the subscription and accessible without additional cost. It is a deliberate, portfolio-based approach: the goal is not to produce blockbusters, but to create additive experiences that increase the time subscribers spend with Netflix properties.

Strategically, this raises an important question: Can Netflix sustain its investment in gaming without clear monetization pathways? Offering games as value-added features may enhance engagement, but it also places them in a crowded market without a differentiated economic model. The challenge will be to justify ongoing development costs in a category where most competitors rely on direct payment models—whether through premium pricing, microtransactions, or advertising.

For now, Netflix is playing a long game. The company continues to expand its library, experiment with various formats, and build the necessary infrastructure for a broader reach. However, as the platform matures, the success of its gaming initiative will likely depend not only on engagement metrics but also on its ability to translate attention into a durable strategic advantage.

PLAY/PASS

Play. Watching Chelsea beat PSG so convincingly was a win in itself. Hearing the crowd boo the type of men who you never see except when they’re trying to take credit for someone else’s effort was a fantastic bonus.

Pass. The passing of Ozzy Osbourne will undoubtedly terrify more than a few in the underworld. Hopefully, we’ll get a proper Fortnite skin to commemorate the Prince of Darkness as well.

UP NEXT

I’m headed up the mountain for the next few weeks, where I plan to finish the first version of my second manuscript. If you see a weary writer wandering, it’s me.

I would add to the first assertion about public companies contraction and Wall Streets understanding wasn’t always that way. Jack Welsh reshaped Wall Street, American financial markets, and with global reach to have that short term thinking. Prior to the 80s, Wall Street was more concerned with long term growth than thinking of the short term

Welsh discovered he could fire people from GE to artificially boost quarterly profits and that MO took over (I wrote a piece on this last year)

In regards to public companies taking risks, I think that’s spot on. I’ve long argued they should allocate a small portion of the budget to that every year (10-15%). It should be focused on small games and trying new things. I recently wrote about how the cut of AA from major publisher roadmaps has hurt creativity

Nintendo, however, has always paid less but been more focused in its approach. Purportedly, as I’ve not worked there, they start projects with a fun prototype and build a game around it. Most companies rush both concept and pre-production to get to full production. That’s a real mistake as if you have a game in full production before it’s fun, the cost has gone way up (trust me, I’ve worked on some of those)

Joost curious if you think smaller, private studios are more likely to be construct more "ethical" games from a monetization perspective.