The SuperJoost Playlist is a weekly take on gaming, tech, and entertainment by business professor and author, Joost van Dreunen.

Right before going on stage, I lost my slides.

I uploaded the wrong file and successfully unlocked a brand new anxiety.

SXSW is a high-profile event. Different from the predominantly cargo-pant-wearing audiences I encounter in gaming, it is a chance to talk to people from different realms of entertainment. Perhaps because the video games industry has long existed on the fringes of mainstream attention, it still communicates poorly to people outside of its comfort zone.

Unsurprisingly, that means most creatives from music, film, and other entertainment segments are generally unsure of what to make of gaming. They’ve learned by now that games are “big” but not much else. As I see it, a large part of the fault lies with the games industry’s disinterest in building bridges. It’s in part why it continues to suffer from a lack of transparency and doesn’t have the same breadth of partners.

I also believe that’s going to change.

Each year I’m invited back to SXSW, the room is larger and more people show up—yes, that's a flex. I want to believe it’s because I’m a world-class presenter, but it has mostly to do with an increasing number of questions and growing curiosity. Demand exceeds supply.

That’s a promising prospect. Game makers are going to need allies from outside their industry category. For one, developers are increasingly at odds with their landlords. The various gatekeepers that oversee the ecosystems in which they operate relentlessly impose rules and policies that disadvantage game makers.

I think of it as the corporate equivalent of love bombing: the gradual process of initially overwhelming someone with affection to becoming increasingly clingy and controlling until, finally, a game studio realizes it got itself into an emotionally and financially abusive relationship. It is perhaps the greatest threat to the current market economy of interactive entertainment.

[BTW, exhibit ∞ on the poor behavior of platform holders emerged from the discovery documents in the case between Wolfire Games versus Valve.]

For SXSW, I updated my dataset around the largest game makers and the industry’s power structure. In 2023, eight out of the top ten game makers were gatekeepers, compared to just five a decade ago. Only Electronic Arts and Take-Two Interactive remain the largest independent publishers.

That has resulted in a really tough market environment. Never mind that we’re already staring down a predictable decline following last year’s blockbuster bonanza and the latter stage of the current console cycle. At $125.7 billion, publisher revenue in 2023 was down -2 percent year-over-year. Platform holders, on the other hand, saw their revenue increase to $72 billion, up +5 percent. Last week we learned from Apple what that means: you are no longer allowed to speak to power. Amid mounting fines and lawsuits, Apple shut down Epic’s developer account. It told the firm that given CEO Tim Sweeney’s “colorful criticism of our DMA compliance plan” (which I discussed here), it doesn’t believe Epic Games is going to behave properly.

To make up the difference and escape their reliance on rent-seeking landlords, game makers are pushing into new territory, and with it a new era: games as a platform.

Because it is increasingly costly to build sustainable audiences on mobile and PC platforms where gatekeepers demonstrably operate against the interests of especially small and medium-sized game makers, the industry is pushing into new avenues.

There it finds a willing set of non-endemic partners eager to collaborate. Major media execs have started to notice that audiences are spending more time playing games than engaging in more conventional types of entertainment.

“When we look at Gen Z and Gen Alpha, what we’re seeing is that gaming is the No. 1 entertainment choice over video.” — Dennis Kooker, president of Sony Music’s global digital business

And it’s not just younger players. During its most recent earnings, the New York Times showed growth in subscriber numbers. The newspaper added 300,000 net digital subscribers in 23Q4 and crossed $1 billion in annual digital subscription revenue for the first time. It contrasted starkly with outlets like The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, and Business Insider which instead announced layoffs resulting from declining advertising revenue and social media traffic.

“Wordle brought an unprecedented tens of millions of new users to The Times, many of whom stayed to play other games which drove our best quarter ever for net subscriber additions to Games.” — Meredith Kopit Levien, NY Times CEO

It amounts to the following observation: at the same time that game makers are actively exploring novel revenue models and distribution innovations, consumer brands are leveraging interactive entertainment to establish a new relationship model with consumers.

Combined, the two intersecting trends of rent increases and interactive entertainment’s efficacy at the center of a growing number of businesses, push video games into the era of games as a platform. The next generation of innovation will spring from a mutually beneficial collaboration between game makers and consumer brands. Electronic Arts is already doing it with EA Sports FC. CD Projekt Red’s flywheel is spinning along nicely. And even Mario has announced his next feature film for 2026.

I’ll expand on this idea further over the next few weeks, but first I have to pack for GDC.

In the meantime, you’ll be happy to learn that thanks to the awesome SXSW crew I ultimately recovered my slides in time. Phew. You can download them here.

On to this week’s update.

Events Calendar—GDC 2024 UPDATE

On Monday I’ll be speaking at the Game Executives Cabal 2024 at the Minna Gallery (invite-only), hosted by the folks from Strategic Alternatives. Following Michael Pachter, I’ll have 30 minutes of amplified speaking time to share my thoughts on the current state of play, and what’s next.

On Wednesday I’m scheduled to talk about emerging revenue models at The American Bookbinders Museum as part of a mini-series titled Revenue Optimization in Games. I’m joined by Julian Runge and Brett Nowak. N.B. The event is free but limited to 100 seats.

Due to a scheduling error, I’ll have to miss the opportunity to moderate my GDC panel with Laine. That’s a real bummer, but it is also fair to say that I was probably the least interesting participant. And the new moderator, Chloe Appleby, Program Curator at the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences in Sydney, is a clear upgrade.

BIG READ: TikTok time’s up

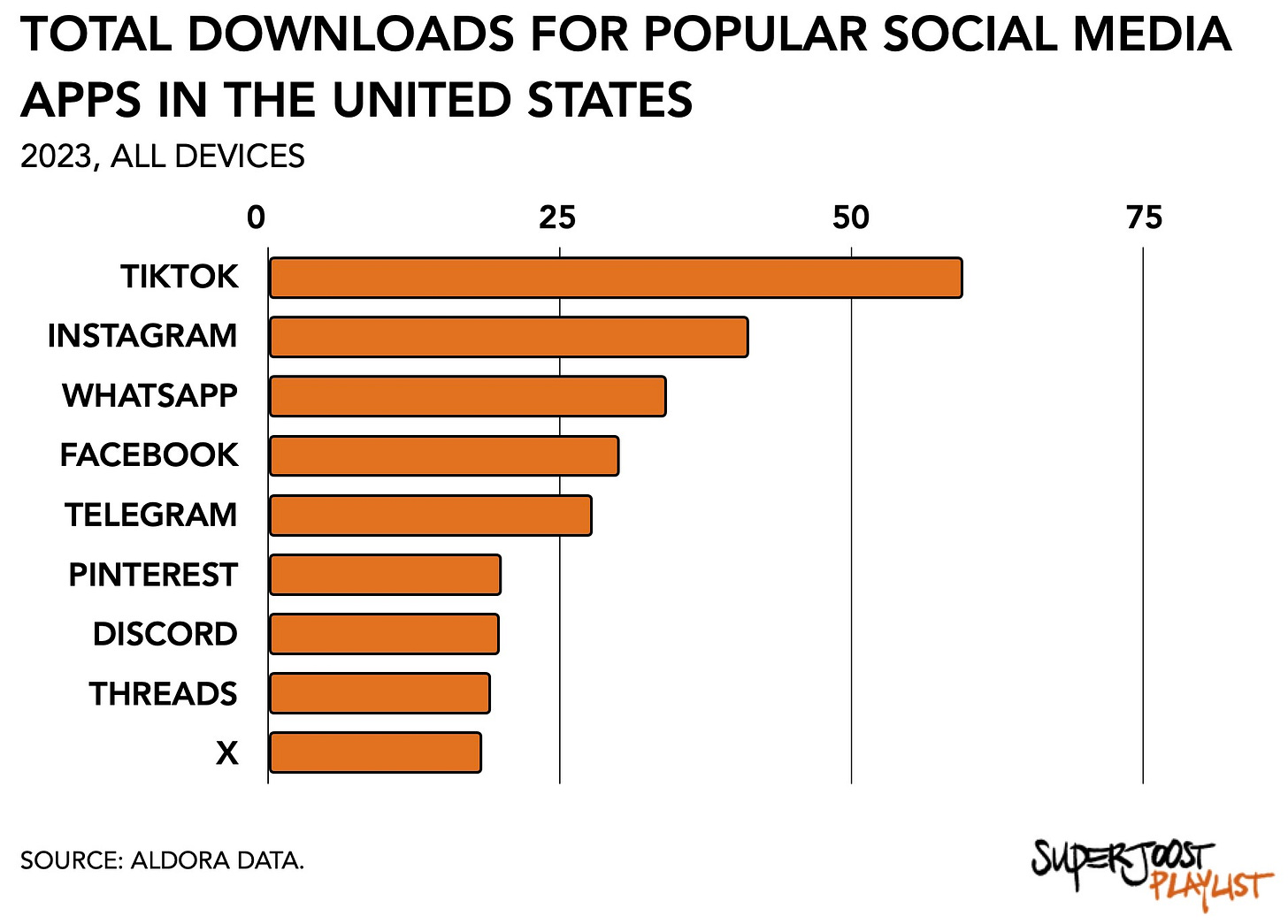

The US government has approved a bill that gives Chinese firm ByteDance 180 days to divest its popular social media app TikTok and prevent being banned from app stores. The app has 170 million users in the United States, generates $16 billion annually, and has become a key marketing channel for millions of small businesses, including game makers.

The anxiety is understandable, if not wholly predictable. In the run-up to the US elections, policymakers are worried the popular app may unduly disrupt or disadvantage the democratic process. The core argument revolves around two aspects: first, the collection of American user data by a Chinese company, and, second, the potential to influence its mostly younger user base.

My recent analysis of the 4-hour Senate cringe-fest hearings suggested that politicians aren’t really concerned with affecting change. After chastising a cadre of social media CEOs we were left with precisely zero resolutions. A year ago TikTok faced a similar ban which also amounted to nothing. Politicians are exacerbating the issue by spinning a false narrative of simultaneously being tough on Tech (which they’re not) and protecting US consumers (which they don’t).

Failure to launch

ByteDance first entered the gaming market in 2015, establishing a dedicated gaming subsidiary in 2017. The company initially took a comprehensive approach, acquiring publishing licenses, opening vertically integrated development studios, and purchasing existing developers. It created distinct gaming brands targeting different market segments: Nuverse for core games, Ohayoo for casual titles, and Pixmain for indie publishing.

From 2019 to 2021, ByteDance heavily invested in its gaming initiatives, spending over $5 billion on acquisitions and investments in more than 15 gaming-related companies. Notable acquisitions included Moonton for $4 billion in 2021, C4 Games, and VR hardware maker Pico. The company also established multiple development studios across China. By the end of 2021, ByteDance had elevated its gaming division to be one of its six core businesses, employing over 3,000 people.

Despite some initial successes domestically with casual games published by Ohayoo and the hit title One Piece: The Voyage in 2021, many of ByteDance's gaming projects underperformed or were shut down. The company saw moderate success with perhaps its best-known title, Marvel Snap, in 2022, which generated an estimated lifetime sales of $151 million, according to AppMagic, but revenue was split with IP owners and developers.

Similarly, Moonton's Mobile Legends: Bang Bang performed well but did not significantly grow post-acquisition. Facing lower-than-expected returns, ByteDance began restructuring its gaming business in late 2021, leading to layoffs at Ohayoo, Pico, and several development studios. With gaming generating only $1 billion in a year compared to the company's overall $120 billion total revenue in 2023, ByteDance decided to divest from its gaming segment, influenced by high entry costs, weak title performance, and inability to compete with larger publishers. In November last year, ByteDance announced the restructuring of its games business and will now focus on its core TikTok and Douyin businesses.

For a platform that reaches hundreds of millions of people, you’d expect bigger numbers. Subsequently, if it can’t convincingly push its own titles, its relevance as a user acquisition channel may be more modest than initially assumed.

Foreign media ownership

The looming ban raises questions about foreign ownership of a country’s media and entertainment industry. Central to the question for everyone is to what degree the Chinese government can control ByteDance, and by extension TikTok, to act in its interests. Considering how it has treated other large tech firms like Tencent and the growing number of mysteriously disappearing and reappearing executives, some scrutiny may be warranted.

Historically, the Federal Trade Commission limits ownership of conventional media by foreign entities to 20 percent. With games having emerged as popular entertainment, the question of who owns the different content creators, platforms, and distribution channels deserves the same degree of attention traditionally granted to cinema, music, broadcast media, and other cultural industries.

A generation ago, regulators worried about the lack of access to news media on account of corporate consolidation in pursuit of economies of scale. Small local markets would have severely limited access to broadcast, print, and other news media, which would negatively impact democratic discourse and practices. Technological progress initially carried the promise of unlimited access for everyone. Ownership, it is generally assumed, bears influence on the access to and output of culture industries.

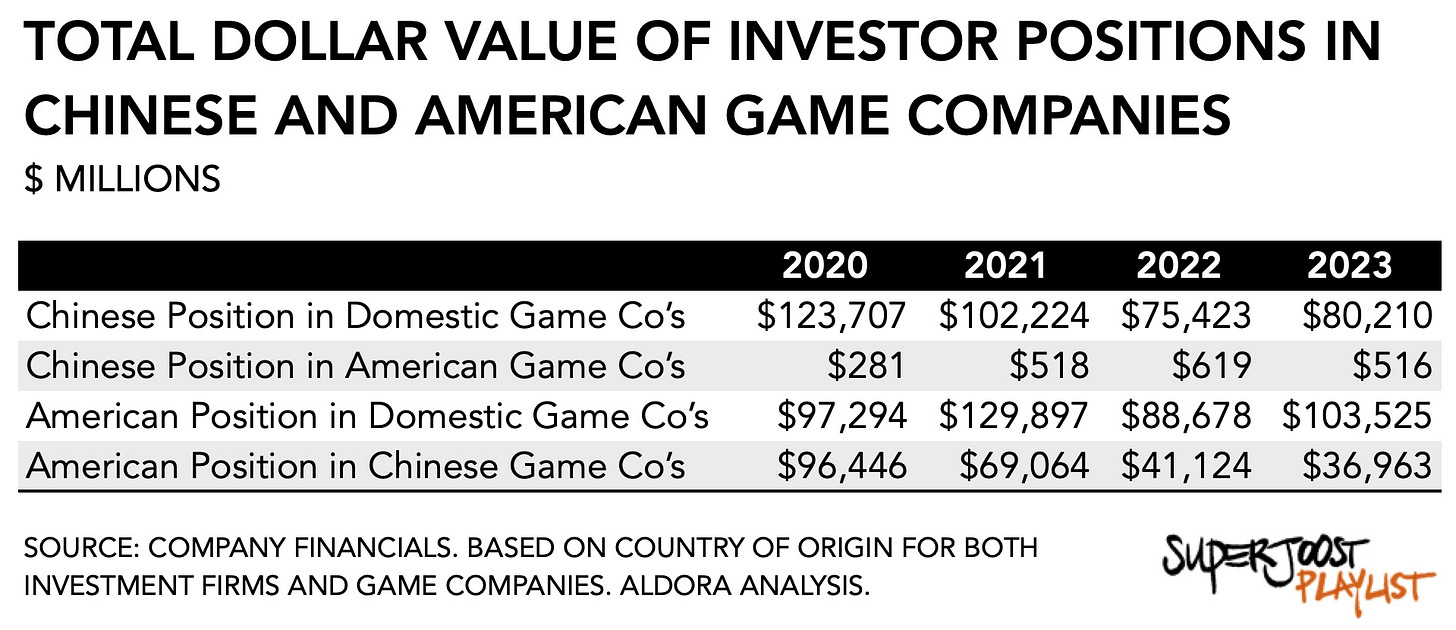

To get right to the point, investors in China seemingly couldn’t care less about the US games industry. In 2023, the total position in US-based video game companies held by Chinese investors totaled $516 million. By comparison, US investors held a combined stake of $36.9 billion in Chinese game companies.

Among Chinese investors, the most popular American entities include the usual suspects: Take-Two Interactive, Electronic Arts, Roblox, and, up until recently, Activision Blizzard. But their shares remain modest around the tens of millions of dollars. American investors, on the other hand, have developed an appetite for Chinese game makers: in 2023, their positions in Tencent and NetEase total $30 billion and $4.5 billion, respectively.

It suggests a broader disinterest from Chinese firms and government officials. That’s distinctly different from, say, the Saudi Arabian government, which spent the past few years aggressively purchasing positions in a broad range of game makers. Its subsidiary, Scopely, announced this week that Monopoly GO! has generated more than $2 billion in revenues since its release 10 months ago.

The Saudi Arabian’s motivations are both distinctly economic, as they attempt to reduce its reliance on oil, and political. While much more overt, the Saudi’s push is also of much less concern to policymakers because it doesn’t interfere with their job renewals.

In the case of TikTok, researchers have concluded that TikTok does not collect any more data than other mainstream social networks. Does TikTok advocate its interests on its own platform to a targeted demographic? Of course! But that’s not a new practice. In 2018, the Sinclair Broadcast Group, the largest broadcaster in the United States with 193 television stations, issued a script to be read, word for word, by its many news anchors. At the time the firm was facing scrutiny from regulators for its proposed acquisition of Tribune Media for $3.9 billion and solidify its market position.

Several large US tech firms have started to get excited about the prospect of potentially acquiring TikTok at a discounted rate. In an attempt to sever the firm’s ties to China, regulators are advocating for ownership by an American consortium. It feels like a double standard, to say the least. More so, I’m unclear why, suddenly, American platform holders are a better alternative. Devaluing and eroding TikTok is a great way for incumbents to maintain and strengthen their existing chokehold on how games are marketed.

If, like social media, the games industry presents a critical avenue for the manipulation of foreign nations, you’d expect investors to follow suit. Instead, Chinese investors have little stake in the US games industry, especially compared to massive US investments in Chinese game companies. Maybe we can take a look into bolstering the position of creative firms in the suffocating platform ecosystem as we count down TikTok’s remaining 180 days instead.

PLAY/PASS

Play. While Apple complained about Tim Sweeney’s “colorful language”, the lawsuit against Valve offered another timeless email exchange in which he calls Valve’s leadership team a bunch of “assholes.”

Play. After committing itself to recognize unions and earn support from the Communications Workers of America on the ABK/MSFT deal, Microsoft has made good on its promise. Promptly, a 600-strong union of QA workers has emerged.

Great update Joost!